A couple of weeks ago I went to see the Yoko Ono exhibition at Tate Modern in London. I’ve been putting off writing about it because, well, I didn’t quite know what to say. It is a huge show spanning a prolific creative life over more than fifty years, and frankly any contemporary artist that has a retrospective of this size in one of London’s biggest public art galleries is surely worthy of serious consideration.

Ono is a much maligned and misunderstood figure in the popular culture of the past half century because of her marriage to the musician John Lennon. She’s the incarnation of the idea of female manipulation: a siren who lured Lennon away from the lads and broke up his band The Beatles. All nonsense of course, but because of this narrative she has been the target of possibly the worst, most vitriolic criticism that any female artist has ever received. The misogyny and racism directed at her over the years has been extreme; it’s the kind of abuse that makes me rage against our patriarchal system.

So I was already primed to embrace her career’s work and come away thinking how underrated Ono has been. And I really tried. But the speed at which I walked through the exhibition spoke volumes: I was almost as quick as my students were — and that’s saying something.

Now don’t get me wrong. It’s not that there was nothing interesting to see here. There were at least three works amongst the more than 200 on show that made me linger more than a minute. I’ll come back to those. But I have to admit I found most of it a bit boring and some of it cutesy and quite naff. There wasn’t much depth to a lot of it. That’s fine in itself — it’s not a requirement for art to be deep or hard to understand to be considered ‘great’. Look at the success of the Impressionists, for example.

But it did make me ask once again a question that I don’t have an easy answer to, which is what makes an artist ‘great’? As much as I want to consolidate the groundswell of critical opinion that is positively reassessing Ono’s artistic legacy, all I can say is that I can appreciate her art as a part of our cultural history but most of it I think is completely uninteresting.

The most significant part of her career in this sense was in the 1960s. At this time artists were once again breaking the boundaries of what art could be, developing in different directions the conceptual work that the Dadaists of the early 20th century had begun. Lots of experimenting with words, with the body, and with audience participation.

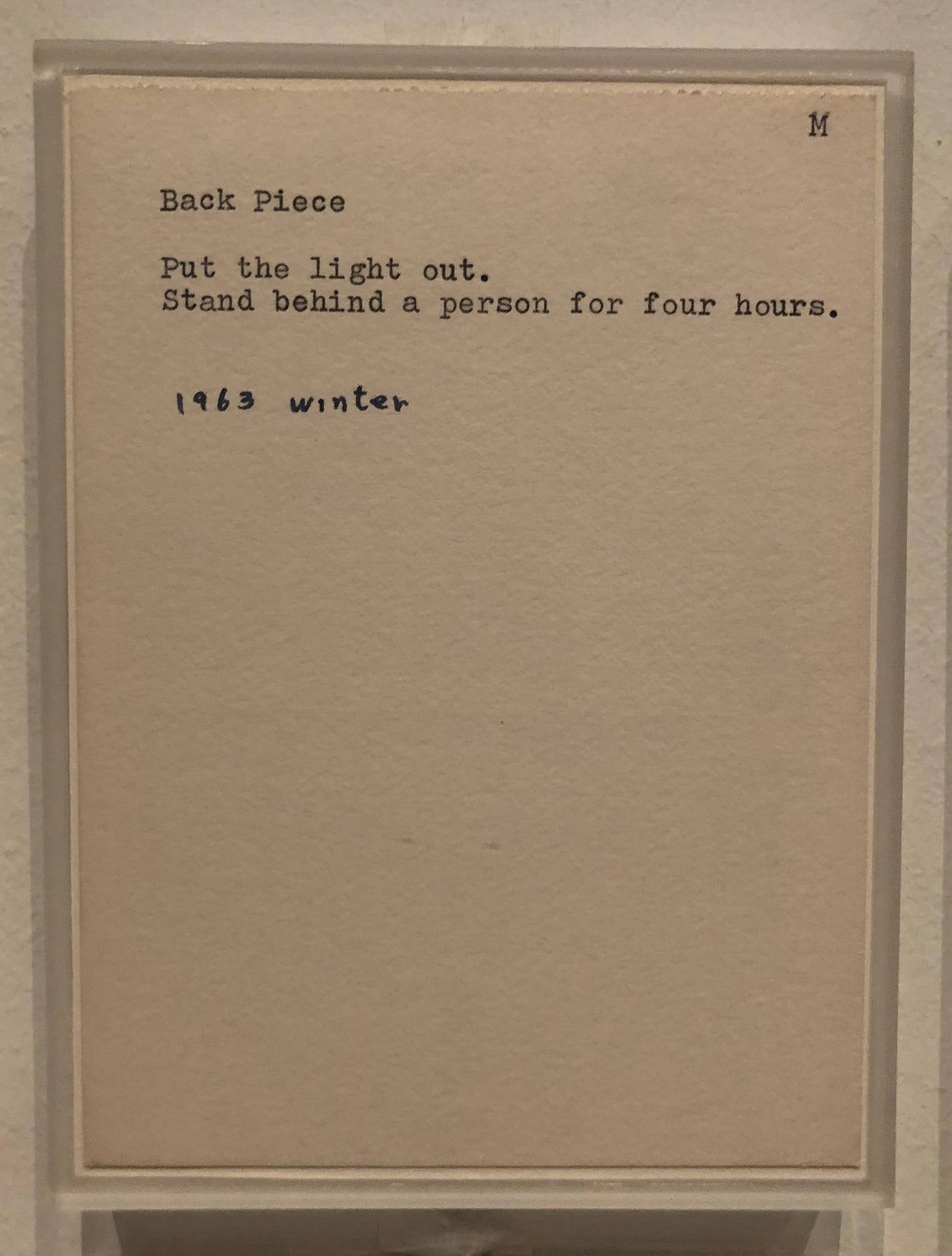

Yoko Ono was groundbreaking in all of these areas after being influenced in her education in the 1950s by experimental musicians and artists like John Cage and George Maciunas, who emphasized how art could be made by anyone and could happen anywhere. We are used to this idea of art now, but it was radical at the time. Ono’s early text-based ‘instructional’ pieces developed this idea, describing artworks in words typed on sheets of paper, leaving the viewer to complete the piece by doing the action, or even just imagining it.

Her book Grapefruit, published in 1964, is page after page of these ‘instructional’ artworks. Each one is thankfully short, often quite surreal and dreamy; but after a while they become a bit tedious. In Dawn Piece from 1963, for example, Ono instructs the viewer to ‘Take the first word that came across your mind. Repeat the word until dawn’. In Painting to be Constructed in Your Head (1961) we are told to ‘Look through a phonebook from the beginning to end thoroughly. List all the combinations of figures you remember after that.’ There’s only so much of this I can read.

The curators have tried their best to bring some of this dry, theoretical stuff alive. We are invited, for example, to participate in Painting to Hammer a Nail from 1961 in which Ono tells us to,

hammer a nail into wood every morning. Also, pick up a hair that came off when you combed in the morning and tie it round the hammered nail. The painting ends when the surface is covered with nails.

We are provided with the basis of the ‘painting’ in the form of a white wooden surface, a hammer and some nails, and encouraged to give it a go, closely supervised by a gallery attendant. God only knows why you would though, unless you’re a bored child.

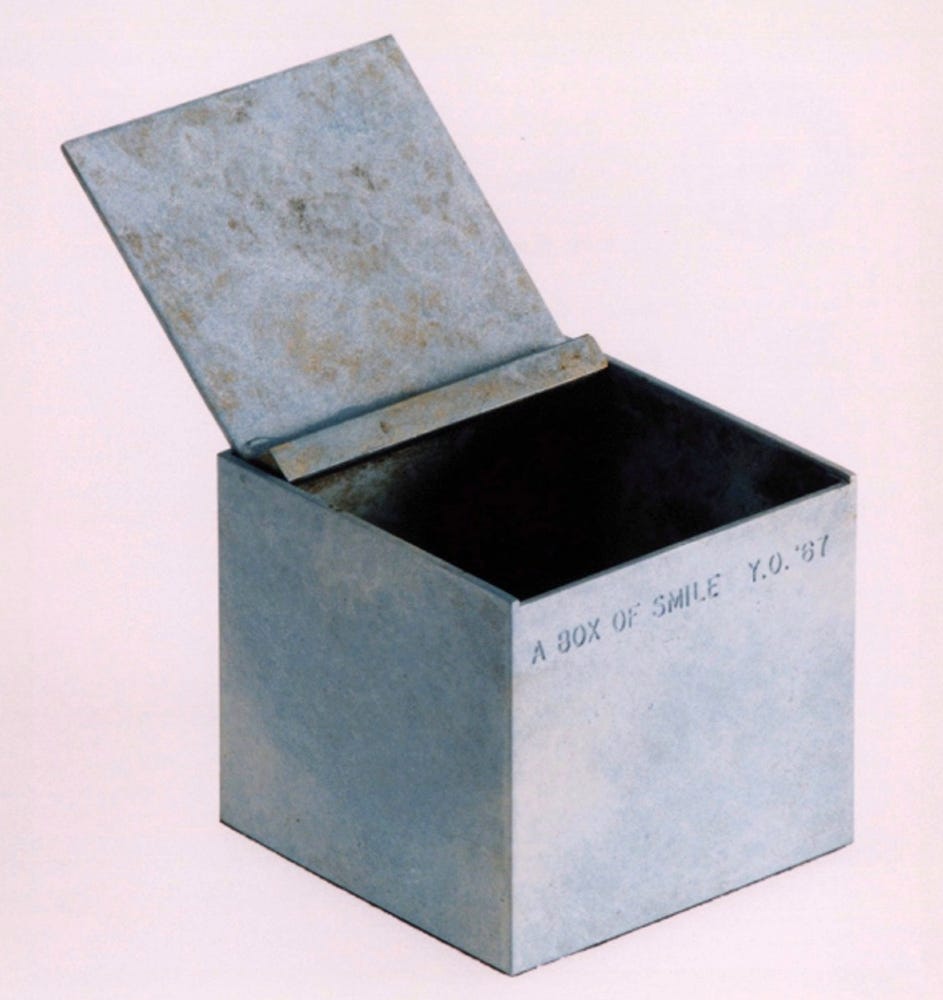

Many art critics have described Ono’s work as ‘hopeful’: shake hands through a hole in the canvas; play a game of chess where no one can win because all the pieces on the board are white; gush out something lovely about your mum on a post-it note and stick it on a wall. But if you’re a cynic like me you’ll be more likely to find the invitations to participate in this sort of thing a bit cringe. I rolled my eyes at A Box of Smile from 1967, which is a mirrored box you are invited to open and smile back at your reflection.

There’s lots of this peace+love messaging in her art, which is interesting in that it situates her early career in the countercultural hippie era. It’s an artistic response to a particular period in our history, and that fact I can appreciate. But a lot of the art itself is as sophisticated as a school project.

It’s only occasionally when Ono actually creates the work from the instructions and documents it on film that it becomes engaging for me. I loved her visual expression of Lighting Piece from 1955. The instruction is brief: ‘Light a match and watch till it goes out’. Ten years later in 1966, when Ono was part of the Fluxus art collective, she made the most beautiful film version of it. In Film No.1 (‘Match’) we see the match being struck and then the flickering flame, shot with a high-speed camera and then played back at a standard speed, burning and then dying away at an impossibly slow rate. I was mesmerised by it and watched it all the way through, twice.

There are a couple of other films that stood out for me too. Firstly, it was interesting to watch again her most famous artwork, Cut Piece, which Ono performed in 1965 in New York’s Carnegie Hall. In this film Ono sits motionless on the floor of the stage with a pair of scissors next to her, which members of the audience use to snip away her clothing.

While some of the audience are tentative in their takings (largely the women), the same man approaches twice — once cutting a hole in her shirt so that her breast pokes through, and later coming back to remove the top half of her slip and cut the straps of her bra beneath. Ono sits passively throughout, though occasionally her eyes flicker, and at one point she moves her arms to hold her clothing up around her breasts. There’s something deeply moving about watching this film. It’s a quiet expression of the powerlessness that women feel in certain situations. And it’s one of the truly great performance artworks of the 20th century.

The other film that stopped me in my tracks in this exhibition is called Fly, directed by Ono and Lennon in 1970. It depicts a nude woman lying on a bed in front of a window with houseflies crawling over her body, accompanied by a soundtrack in which Ono warbles and screeches. I walked in to the screening room just as a fly was making its way over the woman’s labia. I hadn’t read the blurb on the wall before I went in and got quite a jolt faced with a full-on close-up shot of her vagina. It’s not often that I’m shocked by art. Here’s a snippet of it I filmed:

It was an extraordinary short film, and I was deeply engaged right from the start in watching her motionless body as the flies moved over her skin. It was sort of gross but also beautiful. I thought about how controlled the young woman was in not succumbing to swatting the flies away. It must have been ticklish. And the freedom of those flies, going where they wanted. I’m not sure whether Ono intended this as a feminist statement, but that’s how I read it.

This is where Ono’s work is occasionally very powerful and profound. In a recent BBC radio documentary to mark her 90th birthday we get a glimpse of something deeper than the surface-level positivity that dominates most of her work. She said this of her experience of life:

I felt like I was taking life lying down. I think a lot of women feel that way. In terms of survival I think that many times we have probably had to.

These thought-provoking, viscerally engaging works are, in my opinion, few and far between. So I come back to the question of what makes an artist ‘great’? Yoko Ono’s art is heading into the hallowed halls of the canons of Western art history, underscored by art historians, curators, collectors and cultural institutions. But is it because of the quality of her work or the intersection of her life with other significant cultural figures?

Being a pioneer doesn’t make your work interesting, although it should at least get you due credit. Text-based art became a big thing later in the 1960s as it was taken up by male artists who have been given more attention and praise than Ono for it over the years - artists like Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Weiner. This is all of course part of the familiar story that has devalued and minimised women’s achievements throughout the history of art, and is an injustice that many other female artists have had to endure too. I’m sensitive to this, which is one of the reasons why I find it really hard to decide whether Ono’s work is worthy of this level of attention.

As always, Gallery Companions, I’d love to know what you think. Am I being too harsh about Yoko Ono’s work? If you’ve seen the show in London let me know your thoughts on it. And what do you think makes a ‘great’ (as opposed to a ‘good’) artist?