This week I’ve been intrigued by a story that has been in the UK headlines. It’s about the somewhat unscrupulous and highly profitable commercial world of human egg freezing. Now stick with me here, I will get to the art eventually.

Apparently women who are paying to prolong their ‘reproductive window’ by having their eggs extracted and put on ice for the foreseeable are being ripped off left, right and centre by the private medical companies that provide these services. These clinics are not always transparent about costs — which can spiral when you add in the additional hormonal medications that you might need, the annual freezer storage space, and the eventual IVF treatment on top of the basic package.

And now we learn according to a BBC study that over 40% of clinics are potentially in breach of advertising guidance on the success rates for pregnancy. It can be a painful and emotionally draining procedure, and there are concerns that patients are undergoing treatment that they might not need and which might not work anyway.

Back in 2009 there were just 230 egg freezing cycles in the UK, when the technology was used almost exclusively for medical reasons for women who were undergoing chemotherapy or experiencing conditions known to cause infertility. Since then there has been a dramatic rise in the number of women who are having the procedure done for non-medical reasons, in what is called ‘social egg freezing’. The latest data from the UK’s regulatory body, the Human Fertility and Embryology Authority, shows that egg freezing and storage had increased to over 4,000 cycles by 2021, nearly doubling in number in two years from 2019. These statistics are just as dramatic in their rise in the USA.

Clearly there is something going on. It’s partly of course the fact that this procedure exists on the commercial market now and more women know about it, helped by a number of celebrities who have been open about putting their eggs on ice. And with this celebrity endorsement comes the sense that perhaps it’s the normal thing to do. There’s a lot of chat on the internet about the relief and empowerment that women feel once they have done it, describing it as an ‘insurance policy’ against nature and the passing of time. In the BBC documentary Egg Freezing and Me, released this week, the women who opt in to this procedure can afford to do it, and seem happy with their choices.

There are many things about this phenomenon of social egg freezing that I find fascinating: what it says about the strong biological urge to reproduce; the expectations of and on women around career and family; social norms about motherhood; the uses of scientific knowledge; the increasing amount of non-medical procedures that women put themselves through; and the new industries targeting women with culturally-generated anxieties about their ageing bodies.

But what I find most interesting about this story is what doesn’t really get talked about much: who exactly is having these procedures and why. As I was watching the BBC documentary it occurred to me that the connecting threads were the women’s socio-economic circumstances and their age: they were professionally successful, educated, financially solvent women in their mid to late thirties. But the common assumption is that most women who freeze their eggs are twenty-somethings who want to delay childbirth as they pursue their careers. Egg freezing is a way of keeping their options open.

In her recent book Motherhood on Ice, the Yale anthropologist Marcia C. Inhorn has explored the factors that motivate women to freeze their eggs. What her research has found runs counter to this conventional wisdom about the who and why of egg freezing. Inhorn argues that there is, in her words, a ‘mating gap’ — a shortage of partners for university-educated women.

Of the 150 American women she interviewed, just 36 had frozen their eggs for medical reasons. The others were overwhelmingly in their thirties and motivated by partnership problems. 82% of them were single and at or near to the ‘fertility cliff' of 37 when women’s fertility starts to decline significantly. They wanted to be mothers, but couldn’t find suitable reproductive partners who had the three ‘E’s: eligible, educated and equal.

Inhorn’s explanation for the rise in egg freezing is about social class and power dynamics between the sexes. Her research is backed up by demographic data that shows there is a growing educational disparity between women and men in the USA, a situation that is mirrored across the global north. The women she interviewed often talked about their experiences of dating — how men feel intimidated by their success, how they didn’t like being with a woman who is better educated, more accomplished, or makes more money than they do.

Women have historically engaged in hypergamy, or ‘marrying up’, partnering with someone slightly older, better educated and wealthier. And it makes me wonder whether the reverse of this could ever be the norm for men? In another world maybe, but definitely not in this one. It’s that age-old thing that many men struggle with: the threat of powerful women. If socio-economics is the underlying reason why more women are turning to treatments like egg freezing, then the future of co-parenting looks bleak for a large — and growing — number of women.

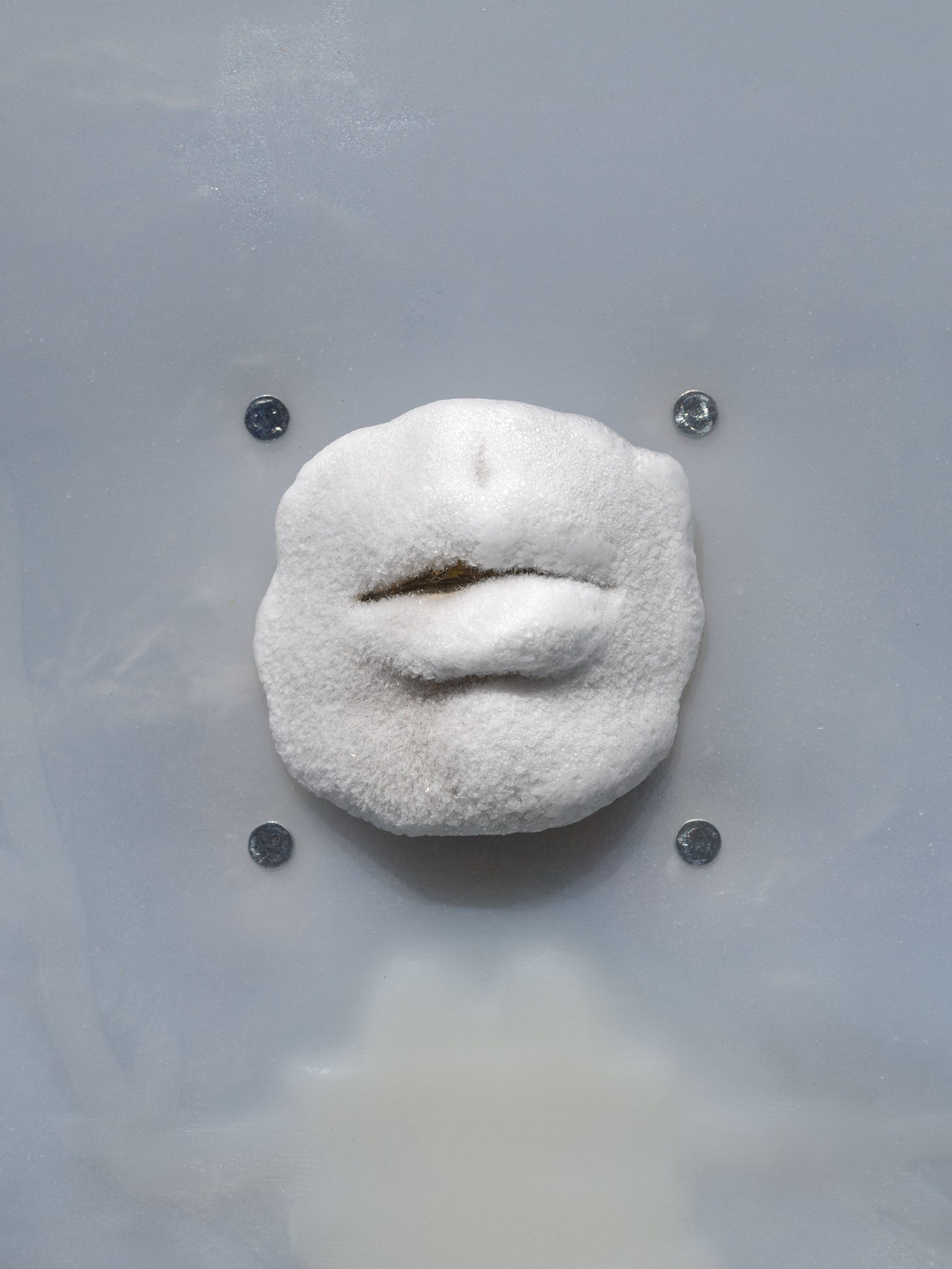

The extension of women’s fertility through science and technology is a subject that the contemporary Chinese-American artist Xin Liu explores in her work. She is at the age now where she is thinking about her own reproductive potential. Friends have advised her to freeze her eggs: ‘Just do it, don’t even think about it’. The frozen mixed-media sculptures in her recent work are inspired by biological and medical innovations in the field of cryogenics and egg freezing. Some resemble bone structures that look warped and twisted as she imagines the changes in her body from these procedures. Liu says this about it:

Reproductive technologies claim to solve all our problems, but in fact dramatically change our bodies. We freeze time in this biological machine because we need to get a better career, we need to go study, we haven’t found a good partner yet. I feel like it’s all about productivity, whether time is useful or not.

In this sense she links our bodies to capitalist ideas of labour, time and efficiency. This is something I’ve written about before. Liu is a believer in the good stuff that comes from science and technology, our ability to change our lives and the world through our ever-increasing knowledge — as am I. But I also agree with her when she says,

let’s hope there’s a limit we can reach, because it also strips away the fundamental idea of what it means to be human. In this calibrated, measured world, art allows beauty and emotion to be part of the process.

I’m really interested in Liu’s art, which is a mix of video art, performance and sculpture. It ranges across different subjects from space exploration to the materiality of oil to ideas of home, reproduction, mutation and more.

This Art21 video landed serendipitously in my inbox this week just as I was thinking about these issues of women’s fertility. And it reminded me once again (if I ever needed reminding) of the value of art to keep it real and human. I think she’s a really thoughtful artist and I’d love to know what your response is to her work and the ideas I’ve talked about here.