This week I’ve been thinking a lot about the practice of looking closely at things. It started when one of The Gallery Companion readers Rebecca Atherfold sent me some wonderful writing and drawings that her boys Henry (age 10) and Rufus (age 9) had done in response to an exhibition in London that I reviewed a few weeks ago. The show is called When Forms Come Alive: Sixty Years of Restless Sculpture, and it explores the history of contemporary static-but-dynamic sculpture.

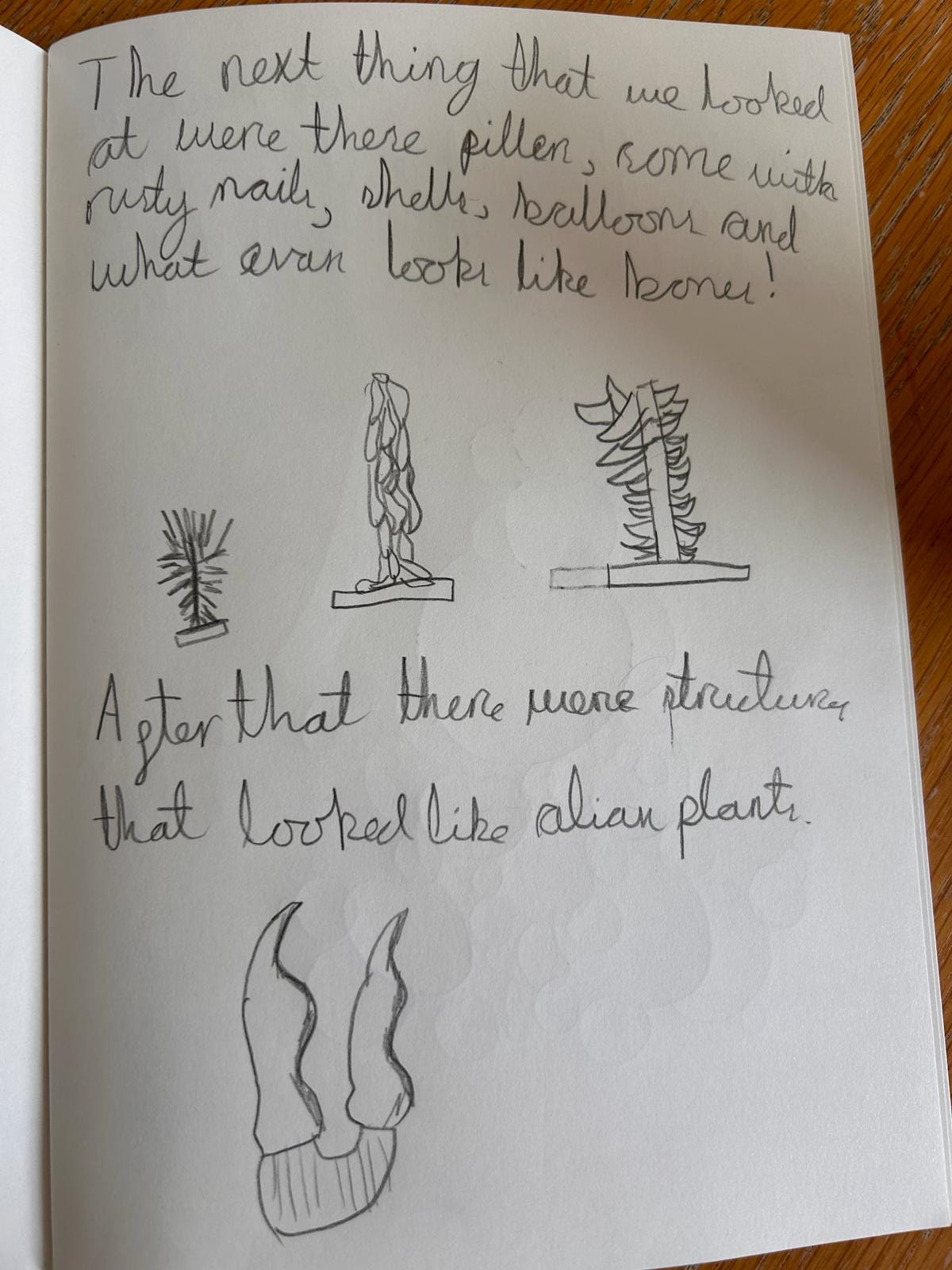

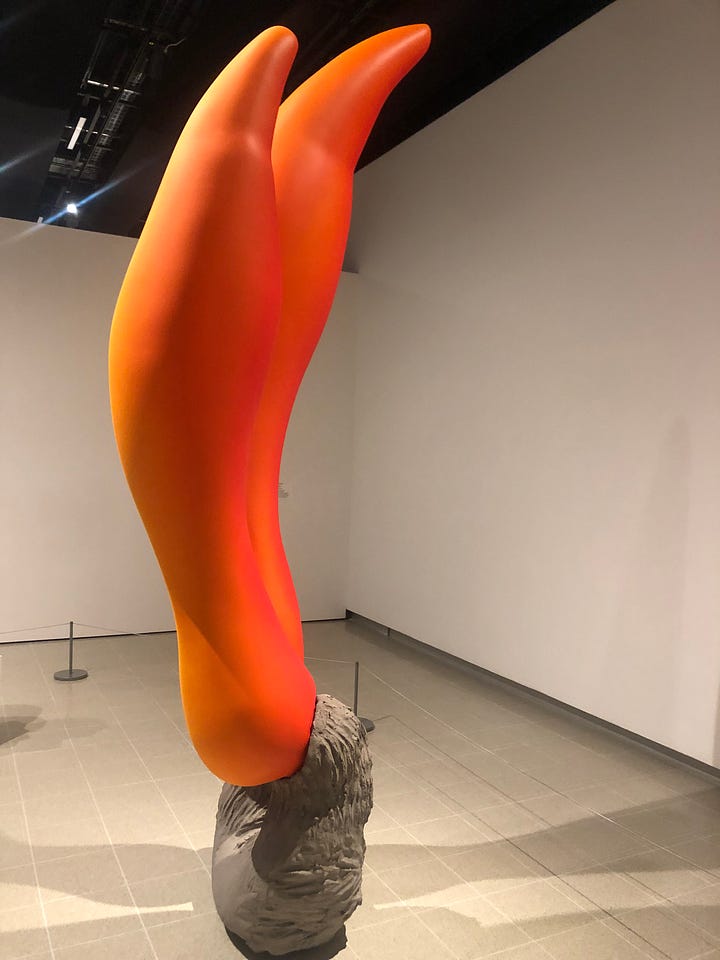

With a brief to write what they thought about the artworks, my young friends spent over an hour deeply engrossed in looking closely at them. Henry drew the sculptures that interested him as well as describing the works in formal and sensory terms, comparing them to things he recognised in the world.

Rufus was philosophical in his response to the artworks, and thought hard about what it could all mean. He said that writing his ideas down helped him decide what he thought. Here’s some of what he wrote:

When forms come alive… what could it mean? What is a form? How is it alive? The first thing I see on my way in is the statue of only the bottom half of a human. Maybe a form is human, as humans are alive?

I’ve just entered and the chandeliers are jumping like jellyfish in the sea! The next piece of art is made of foam. Or at least I think it is. Jellyfish-like lights and foam are both watery, so a ‘form’ could mean watery? Then there’s what I call ‘liquid bricks’ melting over chairs. To prove my point on form meaning watery, the sea is alive, so ‘when forms come alive’ could mean ‘when oceans come alive’.

The critical thinking and stretching of imagination evident in both boys’ observations made me think once again about how valuable art is for children’s learning. This is a subject I’ve written about before. The benefits spill over in every direction, not only in the process of making art but also in thinking about it. Kids learn to identify patterns and structures, think about scale and perspective, describe and question, imagine and analyse.

Then there’s the social and emotional learning that goes on. Contemplating the meanings in art helps children to develop their self-awareness and relational understanding, as well as stimulating them to think critically about the world around them. This recent video from the education team at MoMA demonstrates how they use methods of teaching and learning to effectively engage children in their programmes:

The practice of looking closely, of slow contemplation, is the opposite of what is going on for the majority of children nowadays, according to the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt. Discussions of his new book The Anxious Generation have been dominating my podcast feeds this week, and it sounds like fascinating reading. In the age of social media and smartphones, Haidt argues that the mass migration of childhood from the real to the virtual world has created a generation of kids who are more lonely, risk-averse and anxious than ever.

One of the many compelling arguments Haidt makes in what he calls the ‘Great Re-Wiring of Childhood’ is that current levels of smartphone usage are likely to have a detrimental impact on brain development. The pre-frontal cortex, the area of the brain that allows us to formulate tasks and carry them out with sustained concentration, develops rapidly between the ages of 11 and 16. And just at that crucial age we are now giving our children devices that are designed to distract them constantly. The American teenager receives 250 phone notifications per day on average. That’s 250 times a day when their attention is interrupted.

It has always been hard to get teens to focus on their homework, but doing it repeatedly day after day helps a child’s brain to develop good executive function. Without this training of their young minds, Haidt asks what this might mean for their functioning in adulthood. This podcast interview with him is really interesting (and concerning) listening:

But back to the art of looking closely. As I was scrolling through my Instagram feed this week one image I saw made me look longer than a second. It was a photo of two manhole covers on a pavement, posted by the artist Tiffany Arntson:

The accompanying words read:

ATTEN-SHUN!

Two dots.

Also...

a colon without a sentence

2 circular grids

64 squares

2 embossed WATER signs

6 fluffy white broken blossoms

some moss

a grass stalk

many raindrops

1 square foot of tarmac

Things like this sometimes catch my eye as I pass. It looks like nothing, but there’s enough of a pull to make me turn and look again. Then look some more. I find something in the looking but I’m not really sure what. Attention. That’s what. It kept me staring at this small patch of pavement. When you pay attention, and follow the thread that’s pulling you, there is an intangible connection to be had. Don’t shun it. Especially when it looks like there’s nothing there.

I spent a good few minutes staring at this photo, looking for all the things that Arntson saw in it, and thinking about the way our minds go here, there and everywhere. I love the relationship between images and words in Arntson’s creative practice. It’s like a double shot. Looking, and then being gently encouraged to look some more.

Arntson’s practice of sustained looking reminded me of something I heard the British landscape painter Rackstraw Downes say about what he calls ‘the wandering eye’. He says, ‘you don’t see an image part by part, it unfolds’. When he looks at his surroundings he sees height, depth, unusual shapes and structures, the drama of light moving across the space. And he is constantly learning as he transfers those elements to his canvas. The interest that initially attracts Downes to paint a scene disappears as he gets caught up in the details of what he’s looking at and the challenge of how to represent them on a flat two-dimensional surface with coloured paint.

In this video he talks about his practice of close looking. I found his thoughts on truth, perspective and painting as a metaphor for reality really interesting:

As always, Gallery Companions, I’d love to know your thoughts on any of the ideas and artists I’ve talked about here. And give Henry and Rufus some feedback on their exhibition reviews — I’m sure they will be reading your comments.