What's the Value of Teaching Art in Schools?

Reversing the anti-art mindset

For the past thirty years I have had a recurring bad dream which comes to me every so often when I’m feeling really worried or I’ve got an important deadline looming. It’s always the same. In this dream I’m 16 years old and I’m sitting in a maths exam. The clock is ticking and my mind is frozen. I’m staring blankly at the numbers on the exam paper in front of me and I’m trying to get my brain in gear to work out the formulae and calculate the equations before time runs out. But the sums are like double Dutch and I can’t do it. I always wake up in a cold sweat from that dream.

Maths was the subject I struggled with the most at school. I just didn’t enjoy it at all. It was anxiety-inducing. And it was a huge relief to me when I was no longer required to study it. So it was a hard ‘no!’ from me last week when the British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak suggested that studying maths should be compulsory for all young people until the age of 18. Sunak wants to reverse what he sees as an ‘anti-maths’ mindset in the UK because he says there’s ‘a cultural sense that it’s ok to be bad at maths’ and claims it costs the country ‘tens of billions a year’. He’s concerned about productivity and the growth of the British economy, and in his view extending maths education for two years longer will help sort out that problem.

Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not intending to do any maths-bashing here. I absolutely believe in the fundamental importance of learning maths. Basic arithmetic, algebra and geometry are crucial life skills which also develop our abilities in problem-solving, logical reasoning, sequencing, systems recognition and abstract thinking. This is all good stuff for young minds.

But I’m really not sure what Sunak is on about with this ‘anti-maths’ mindset chat. Maths is front and centre of the national curriculum here in the UK. For many years the focus in the English state school system, where the majority of kids aged 5 to 16 receive their education, has been on just three ‘core’ subjects: maths, science and English. The only other compulsory subjects for pupils aged 5 to 16 are PE and computing. Other arts and humanities subjects such as history, geography, art and music are only compulsory until the age of 14. And they don’t have anything like the same value placed on them or timetable weighting given to them as the three core subjects do.

This issue has got a long history. The content of the school curriculum has been the subject of debate on and off since the middle of the nineteenth century. And the knock-on effects on the strength of the economy from children’s education has been at the heart of those debates. In the Victorian era the changing needs of a growing workforce required certain skills from school-leavers. In particular there was an increasing call for a solid foundation in reading, writing and arithmetic for office work, as well as practical knowledge of science and engineering. Sound familiar? Then just as now, there were concerns that the restrictive focus on the three Rs, although practical in terms of preparing a child for the workplace, didn’t broaden minds. It wasn’t creating rounded, thoughtful citizens, and this was a worry for the Victorian ruling elite at a time when more and more men were gaining the vote.

The big question has always been what is useful knowledge? Given the concerns about the health of the British economy now and the way in which politicians are linking it to the education system, it’s surely time to have a proper debate once again about the purpose of education, what we think school is for, and what the curriculum should look like in the 21st century. And in that debate we should look at new evidence on the value of the arts in children’s learning.

Last month the Gulbenkian Foundation published a report The Arts in Schools: Foundations for the Future, in which they made a strong evidence-based case for the benefit that teaching art, drama, music and dance to schoolchildren brings to productivity and the economy as well as to society more broadly. The authors argue that integrating the arts into the curriculum can help children understand STEM subjects more effectively. The arts also help children to develop relational thinking and empathy towards others, building the groundwork for stronger social cohesion. By enriching our human experience the arts have the potential to make us happier, healthier and more whole. And they reinstate the idea that education for work and education for life should be inextricably linked, with the arts in a connecting role.

This is something that the American artist Ruth Asawa (1926-2013) spent a large part of her career championing. She argued that the skills that you learn through making art are essential to cultivating creative thinking within all fields of knowledge. Asawa said the line of distinction between so-called ‘academic’ subjects and arts subjects is a false dichotomy. The process of making art uses all the skills that are necessary to grasp literacy and numeracy: identifying patterns, structures, thinking about scale and perspective, close observation, the process of describing, questioning, imagining, problem-solving. The process of doing rather than just thinking about abstract ideas, gaining experience rather than passively absorbing information, trains children’s minds, no matter what career path they take. Art should therefore have equal status with core subjects like maths and English, and should be integrated into subject learning rather than separated from it.

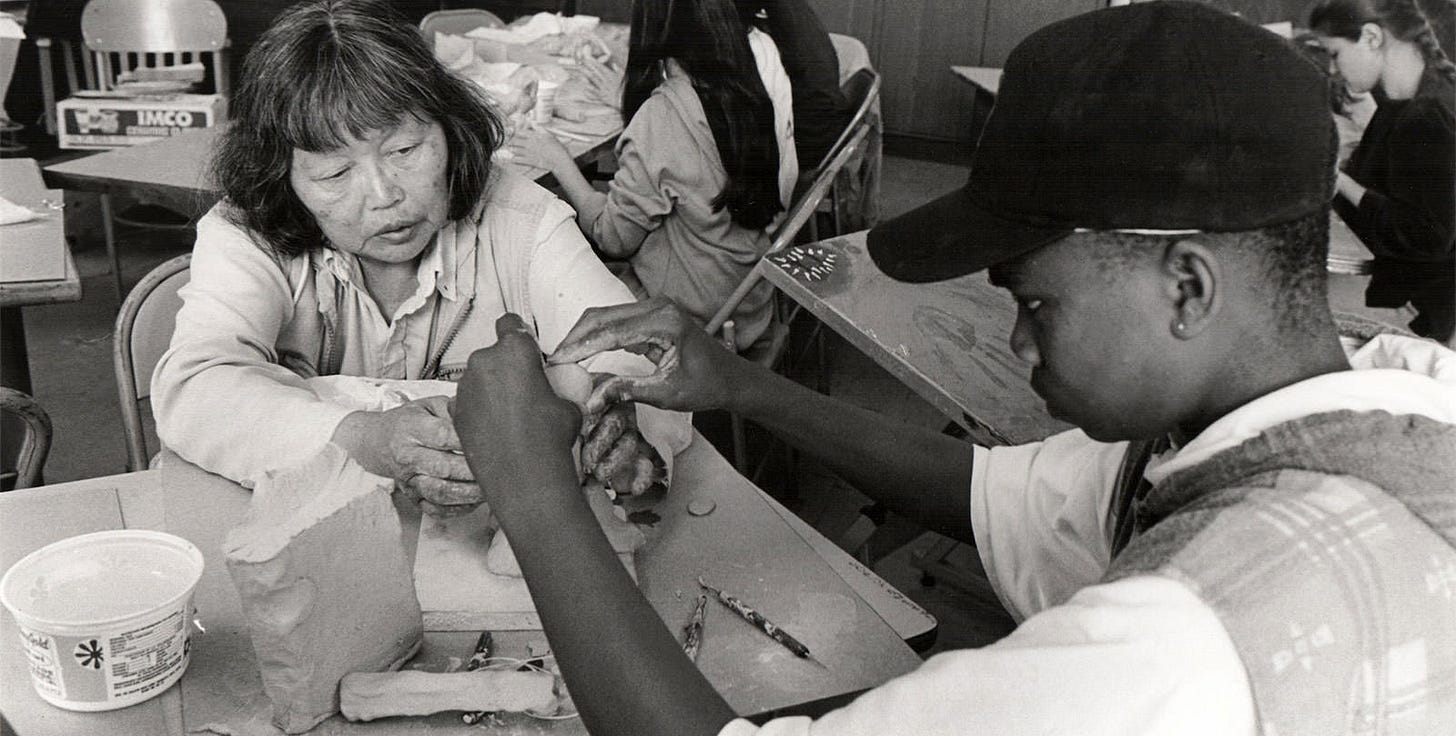

Asawa’s educational philosophy is inspiring. She first made this argument about the value of art in our children’s education more than 50 years ago. In 1968 she founded the Alvarado School Art Workshop to give children access to art education so that they could develop more fully as individuals. It was an innovative programme that involved parents and professional artists in public schools, and at its peak extended to 50 schools in San Francisco.

Asawa developed this thinking in the years after WWII when she attended Black Mountain College, an experimental liberal arts university in North Carolina. The programme of study there was broad, but essential to it was the idea that making art was integral to any learning. One of her tutors at Black Mountain was Josef Albers, who was one of the most influential teachers of visual art in the twentieth century. He taught Asawa about the importance of experience rather than abstract knowledge as a way of finding truth. What that means is that through the process of doing something, working with different materials, drawing the things you’re observing, you’re not just looking at it, you’re actually coming to understand it better. That is active rather than passive learning, and with this learning approach you’re far more likely to come to understand structures and processes. Essentially it’s deep learning that can be applied again and again.

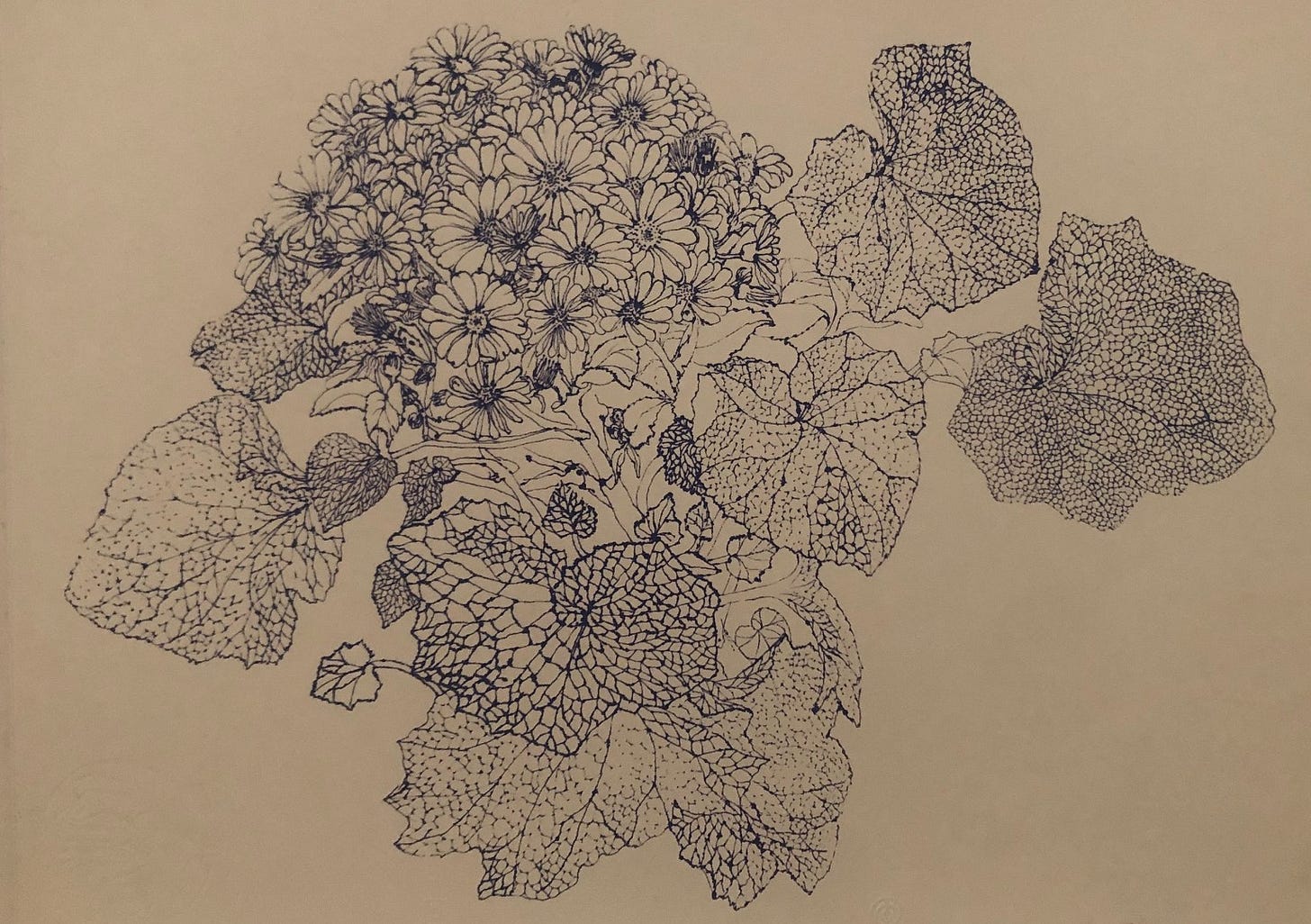

You can see these ideas in Asawa’s art practice. She made organically-shaped abstract sculptures from metal wire in a continuous mesh, which she constructed meticulously by hand. They are wonderfully intricate sculptures that command their own space and the areas around them through the shadows they cast. There is something quietly beautiful in the way that they appear soft and weightless, but are in fact dense and tough. In this 5 minute video Asawa explains the ideas in her work in her own words:

Asawa made drawings throughout her life, at any opportunity. Things in nature, the people around her. Drawing was a practice she did every day, as a way of closely observing and understanding the world around her. She wasn’t interested in creating beautiful objects for the sake of it, but rather to understand materials, surfaces, textures and shapes through the process of making and doing. Her sculptures were really just the end result of that process. They were the physical manifestation of a line of enquiry, a problem she was solving. This is the way many artists approach their work, and I think art should be talked about in those terms much more. Art is not only self-expression, it is constant learning.

Back in 2018 the Turner Prize-winning artist and Oscar-winning filmmaker Steve McQueen developed an artwork called The Year 3 Project with the Tate that showed all these good ideas about arts education in action. The project involved thousands of London schoolchildren aged 7 to 8 years old, who participated in the creation of a collective photographic portrait that was eventually exhibited at Tate Britain and on billboards around the city. It threaded together arts practice, storytelling and ideas about identity and community.

During the project professional photographers visited schools to take class portraits and led workshops with teachers that developed the children’s critical thinking about photographs as well as their understanding of photographic processes. Teachers were given additional workshop resources to extend the project further in the classroom over time. Pupils learnt about the composition and framing of images, perspective and observation. And they explored how people can view the same thing in different ways, discussed ideas about the self in relation to others, about their place as citizens in a community, and the difference between rights and privileges. Here’s a short video on the project:

It’s precisely these kinds of multifaceted, holistic projects that spark imagination and curiosity in children, and build their confidence. And it speaks to the educational ideas that Ruth Asawa was so passionate about. She summarised the value of arts education like this:

A child can learn something about colour, about design, and about observing objects in nature. If you do that, you grow into a greater awareness of things around you. Art will make people better, more highly skilled in thinking and improving, whatever business one goes into, or whatever occupation. It makes a person broader.

Asawa is describing here the importance of inextricably linking education for work and education for life. For her making art was not only about learning, it was also a social practice. It was about becoming a valuable member of society and contributing to your community in a positive way. By bringing art and the process of making into your life you become a whole person.

What I find really interesting about all of this is that the value of arts education isn’t even up for debate in private, fee-paying schools. Middle-class parents who choose to pay for their children’s education expect them to be taught a broad range of subjects, including the arts. They want their children to benefit from the enrichment and personal development that they get from arts practice. They recognise the fundamental ways of organising and understanding the world that the arts bring as part of a whole suite of learning.

The recent Arts in Schools report points to the increasing inequality of access to the arts. It’s a privilege rather than a given. Children in the most disadvantaged areas are least likely to be able to access cultural activity through school, reinforcing cycles of exclusion and deprivation. How we improve our children’s education is a necessary conversation to have at a national level. But I wonder whether it’s two more years of maths that we need, or different methods of teaching and learning to help pupils understand maths more effectively. Perhaps what we really need is to start reversing the anti-art mindset.

As always I’d love to know your thoughts on any of the ideas and art I’ve talked about here, so please click on the comment button to leave a message.

Artists’ Writing Service

Artists: do you find writing about your art practice difficult? I can help! I provide an artist statement writing service and 1-2-1 mentoring to help you get more clarity on how to express the ideas in your work. Click here for more info and prices.

I’ve just recently worked with the artist Frances Ross on her statement. It was such a privilege to spend time with her and to learn more about her practice. Frances’ work is about the language of colour, and here’s the first part of what I wrote:

Frances Ross is an abstract painter living in North Yorkshire, UK. Her work is a joyful and ever-evolving exploration of the language of colour. This language is primarily about relationships: how colours behave, how they speak to each other, how they generate feeling. Ross likens our response to colours to the associations we might have with particular words: just as words can recall memories, sensory experiences and feelings individual to our personal histories, so too do colours. Her paintings are an expression of interiority, where colours operate together like words in stream of consciousness writing or marginalia on the page of a book. The connections between seemingly uncategorised thoughts are captured in the materiality of the paint and its visible brushstrokes, representing that fleeting moment of clarity that we all experience sometimes.

Follow Frances Ross on instagram here, and click here to find out more about working with me.

I'm sympathetic to the idea that it's a problem how many people think they are just bad at maths, it was taught appallingly when I was in school and I know now I'm actually good at it. But good grief, can't they see that to extend the studies for longer is not addressing the actual problem? I may be biased since my academic background is Early Modern History, but I think we need to revive the Renaissance asap. It was madness to the educated mind of the time that someone would not be a polymath well-versed in the full breadth of human culture. The same Leonardo Da Vinci who painted the Mona Lisa was an engineer, it's absurd that we built a society where we pit things that need each other against each other. I could rant about this all day, I swear. Short-sighted doesn't begin to cover it. I'd rather focus on the positive though and thank you for bringing to my awareness Asawa's work, and I didn't know about Steve McQueen's project either. How awesome. I hope someone can be*ahem* 🙊 instil some sense in the PM.

I couldn’t agree more and I imagine your readers will be on this side. STEM turned into STEAM for a while (with “art”) but it seems to have been short lived. The way you discuss Asawa using lines of inquiry are at the heart of current international and American secondary pedagogical discourse. I wonder if a version of this could go to an educational publication, like TES? (Times Educational Supplement) Really compelling points in response to a misguided government. I need to spend more time with the videos. Thanks for this great read...will share with my teacher network.