Moving Stories: Artists on Migration

Alternative perspectives on small boats and the movement of people

Back in 2015, as the Syrian refugee crisis started to become a very visible issue in the EU, the Irish photographer Richard Mosse began filming the mass migration of people into Europe. In that one year alone more than a million people made the journey to EU countries. The majority were fleeing the conflict in Syria, trying to find a safe country that would take them in. But there were others too - Afghans, Nigerians, Pakistanis, Iraqis, Albanians, Kosovans. People who, for myriad reasons, felt that their only choice was to leave their homes and risk everything to get somewhere else. Desperation was driving them, and the knowledge that what they had left behind was far worse than the gruelling journey they were enduring.

Mosse’s film, which he titled Incoming (2014–2017), captures footage along two pathways leading into Europe — one from Africa, the other from the Middle East—using a specialized surveillance camera that he sourced from a weapons manufacturer. This technology was originally designed for military use, and produces images by detecting thermal radiation, including the heat of a human body, from as far as 30km away. The resulting eerie, black and white images don’t capture people in any recognisable individual sense, although it is possible to distinguish men, women and children. In describing how the technology reads its targets, Mosse says:

The camera basically dehumanizes its subjects and makes them look like zombies by reducing them to their basic biological essence, their heat signature. Among other things, it reads people’s eyes as orbs of viscous black jelly, which makes a mockery of the idea of the eyes being a window to the soul. It really is a deeply sinister technology.

Incoming documents moments along these migratory routes in heart-wrenching flashes: the journey by land on foot or on overcrowded trucks, the makeshift camps, small inflatable dinghies crammed with too many people, rescue teams, limp bodies washed up on tourist beaches. At one point during filming Mosse’s camera captured a human trafficker’s boat carrying 300 refugees as it sank into the waters off the coast of Turkey. Six miles away on the Greek island of Lesbos, Mosse was too far away to help as the people struggled and then disappeared into the sea. In this video he talks about the process of film-making:

This film has been in the back of my mind as I’ve been reflecting over the past few weeks on the UK government’s Illegal Migration Bill, which is currently making its way through the British Parliament. The proposed legislation is intended to deter migrants from making small boat journeys across the English Channel from France. Thousands of people are arriving on the south coast of England by this route every year. Almost all of the people who arrive on small boats claim asylum, and according to current official figures 75% of asylum claims in the UK are granted. But the government’s rhetoric is that people who arrive by this route are predominantly economic migrants trying to enter the country illegally, despite having no evidence for that claim.

Their proposed solution for dealing with the increasing number of small boat arrivals is to refuse to hear any claims for asylum from them at all. Applications from anyone who enters the country by what the government calls ‘irregular routes’ will not have their claims heard, no matter how strong their case is. Most people who are fleeing conflict or persecution will by necessity enter other countries by irregular routes. But even if some of these people are economic migrants they would surely have to be pretty desperate to risk their lives crossing one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes with notoriously strong currents in an overcrowded inflatable dinghy.

The British government proposes to send them all back home, or to a safe third country. And if that’s not possible, they will remain indefinitely in the UK without legal status with the bare minimum of support. That broad brush approach sweeps up everyone, whether their claim for asylum would be valid or not. I do wonder what the politicians proposing these plans think will happen to vulnerable people when they are kept in limbo with little support, whilst being prevented from working legally. Surely that will increase their risk of being exploited by criminals.

People migrate for all sorts of reasons, and often it’s not fear of persecution but because they are seeking food security and work opportunities. The Danish artist collective Superflex captures this idea powerfully in their 2015 film Kwassa Kwassa, set on the tropical island of Anjouan in the middle of the Indian Ocean. A short distance from Anjouan is another island called Mayotte, which is part of the EU, despite being 8,000km away from the European continent. It’s a tiny island located off the southeastern coast of Africa, somewhere between Madagascar and Mozambique, with a population of just over 300,000. It’s one of nine territories, including Madeira and the Canary Islands, that are part of the outermost regions (OMR) of the European Union.

Mayotte is officially a department of France and as such it is governed by EU law, its currency is the euro, and it has all the rights and duties associated with EU membership. Living standards there are considerably lower than in mainland France, but since the referendum of 2009 when Mayotte’s citizens voted to become part of France, there has been a huge improvement in public services and infrastructure.

As the Syrian refugee crisis unfolded back in Europe, Superflex was invited to Mayotte by the French Cultural Ministry to create a public arts commission. What they found was an ongoing political situation between Mayotte and its neighbour Anjouan involving a recognisable mix of small boats, people smugglers and border controls. With its EU status, Mayotte is now a magnet for residents from Anjouan who make the 70km journey across shark-infested waters in search of a better life: more job opportunities, good healthcare and education. At this far-flung border of Europe uncontrolled movement of people and human trafficking has become a problem.

Kwassa Kwassa means ‘unstable boat’ and the film focuses on the construction of a small fishing boat by a craftsman on Anjouan. It’s a beautifully-shot film, and the process of hand-making the vessel is mesmerising to watch. You really get a sense of the materiality of the boat and the almost-loving effort and skill required to construct it. But that methodical care in the construction is set against the uneasy feeling that the boat will be used to transport migrants, and that some of them won’t make it all the way. In this fascinating video the artists describe the development of the project, interspersed with scenes from the film:

What’s really interesting about the Superflex film is that it demonstrates the sheer complexity of migration, why people make the decision to leave their homes and risk their lives to move to another place. They don’t always have a gun at their heads, but does this make their reason for moving less valid, does it negate the compassion we should feel for them?

With the environmental problems that climate change will bring in the coming decades - desertification, flooding and the struggle for survival in increasingly inhospitable areas of the world - there will only be more people on the move. It’s not just political persecution that creates refugees, and as a global community we need to rethink the way we consider migration. As Richard Mosse says,

Our subjectivity is crucial to any story about refugees landing on our shores. This is because we are responsible for how we perceive the refugee crisis, for our changing attitudes towards refugees, for the Byzantine process that welcomes them, and for many of the problems that forced them to abandon their homes in the first place.

The emotive language that some politicians use, with words like ‘invasion’ and ‘swarms’ and ‘criminals’, demonises vulnerable people and stokes up xenophobia. This directly impacts people’s lives and safety, and should be called out whenever it occurs.

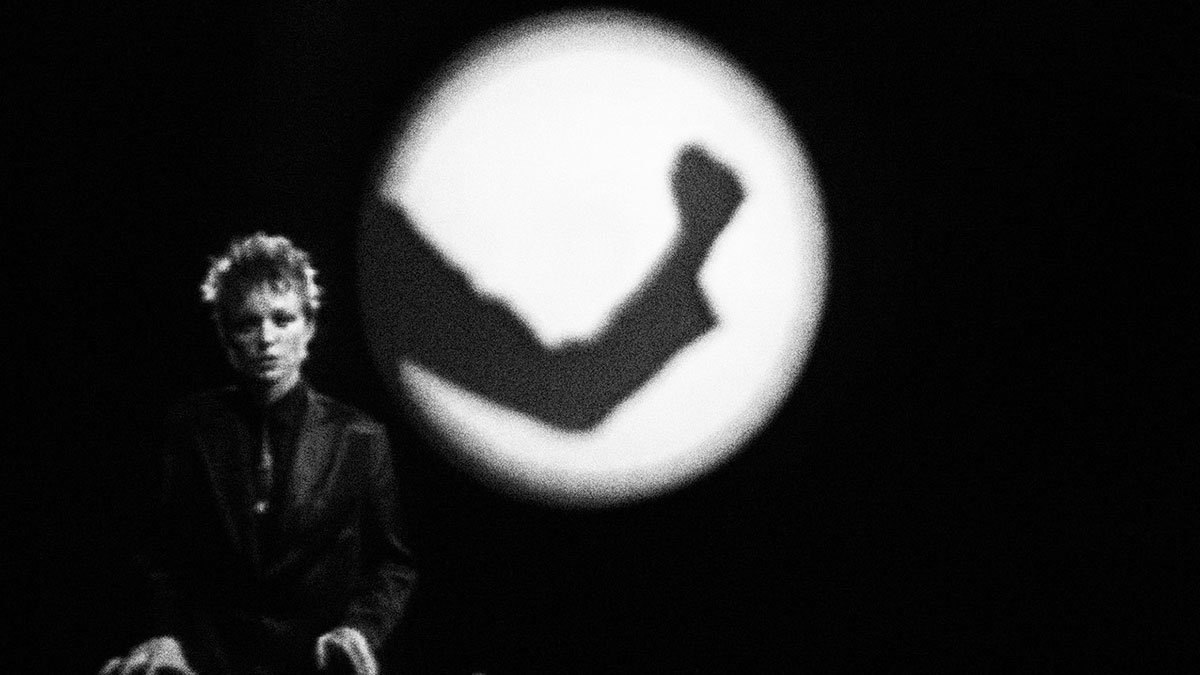

The American performance artist Laurie Anderson has recently talked about how we are in a media-fuelled ‘constant panic mode’, and she advocates for a wholesale mind-shift in the way that we think about migrants. I always find Anderson inspiring. She is a pioneer of electronic music and is known for her spoken word albums and multimedia art pieces, including the haunting 1981 work O Superman.

Anderson’s art combines politics, storytelling and technology, and over the years has become increasingly focused on human rights issues. She says, ‘you cannot close your doors anymore, everyone’s banging on them and you’d better figure out what to do – and see the positive thing in that.’ For Anderson this global blending of people is inevitable and also exciting. We are constantly expecting something bad to happen, and we’ve got to try and see the good in it, she says, because fighting it and being angry won’t help:

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has warned that the UK’s Illegal Migration Bill in its current proposed form would set a precedent amongst signatories that could lead to the collapse of the system of international protection for refugees. Dealing effectively with the millions of people in the world who are currently displaced surely needs more global solidarity and collective responsibility-sharing, rather than an approach that essentially closes the shutters.

Managing migration in a sustainable way is a complex issue - there are no easy solutions for any country. But refugees and migrants are not someone else’s problem: movement of people is the reality of our global community and it’s an age-old historical phenomenon. In 1967 the American artist Claes Oldenburg (1929-2022) made a drawing proposing a new monument to replace the Statue of Liberty, which I wrote about in a previous post. Instead of the welcoming figure of freedom and hope that migrants had historically seen as they entered New York harbour, his proposed statue of an enormous rotating electric fan seemed to say ‘blow them all back where they have come from’. Oldenburg’s fan would not look out of place on the south coast of England right now.

This artwork points to the history of debates around immigration in developed countries and gives us a longer view on issues that are still pertinent today: competing ideas about freedom of movement, economics, national identity and how to deal with humanitarian crises. It’s not an artwork that takes political sides, and neither are the others I’ve talked about here. What the artists do is present ideas in an aesthetic language that gives us alternative perspectives from those we see every day in the media. They have the power to communicate complicated and difficult narratives and to find ways beyond words to show us our common humanity. This is something that feels lacking in our current political discussions on migration.

I know this is a subject that divides opinion, but I am always hopeful we can find common ground in respectful discussions. I’d love to know your thoughts on any of the ideas and artworks I’ve talked about here.

Artists’ Writing Service

Artists: do you find writing about your art practice difficult? I can help! I provide an artist statement writing service and 1-2-1 mentoring to help you get more clarity on how to express the ideas in your work. Click here for more info and prices.

I applaud these artists who are trying to bring sanity and humanity back into this topic, and I also find Orna Ben ami's work very touching. It's sad that this should be framed as an "alternative" perspective, but even sadder that there is now a refugee art industry, quite far from these sensitive approaches, seizing on the subject as the quickest route to attention and profit. It's a very thin line to walk between amplifying refugees' voices and speaking for/over them. I came here as a "refugee" myself, I was in a position to get on a plane and be here legally but I still had to leave my life and home behind to start over from nothing, and it completely sucks; you never stop wishing you hadn't had to leave. And I have left behind so many people who could technically leave, but can't face it and instead have chosen to waste away and die in their home. To imagine people would risk their lives on a boat to go on a lifelong exile if they had ANY other option, is a disingenuous fantasy.

I listened to this article first on your podcast then went to see the images and videos. The podcast is fantastic -- without the images first we have the experience of entering your mind and imagining these artists’ works. Then the images add another layer. As you say, art has the power to show us these nuances. It can go deeper with emotions and push ideas further. I found it useful that your post shows us the terrible heartbreak like the sinking ship caught on film and then the optimism of Anderson. I have researched migrants in fiction films (not refugees specifically) and what the filmmakers often play with is the way people don’t know the facts when they decide they don’t want migrants to come into their spaces. The more information they have, the more they tend to want the migrants allowed in. I know this is a generalisation but something I’ve seen repeatedly through a variety of research. Thanks for this and what a great post to start your podcast.