What a Giant Sculpture Of An Electric Fan Says About Attitudes Towards Immigrants

Claes Oldenburg’s proposal to replace the Statue of Liberty

In 1967 the American artist Claes Oldenburg (1929-2022) made a drawing proposing a new monument to replace the Statue of Liberty. It was part of a series of drawings of fantastical sculptures Oldenburg was working on in the late 1960s called ‘Proposed Colossal Monuments’.

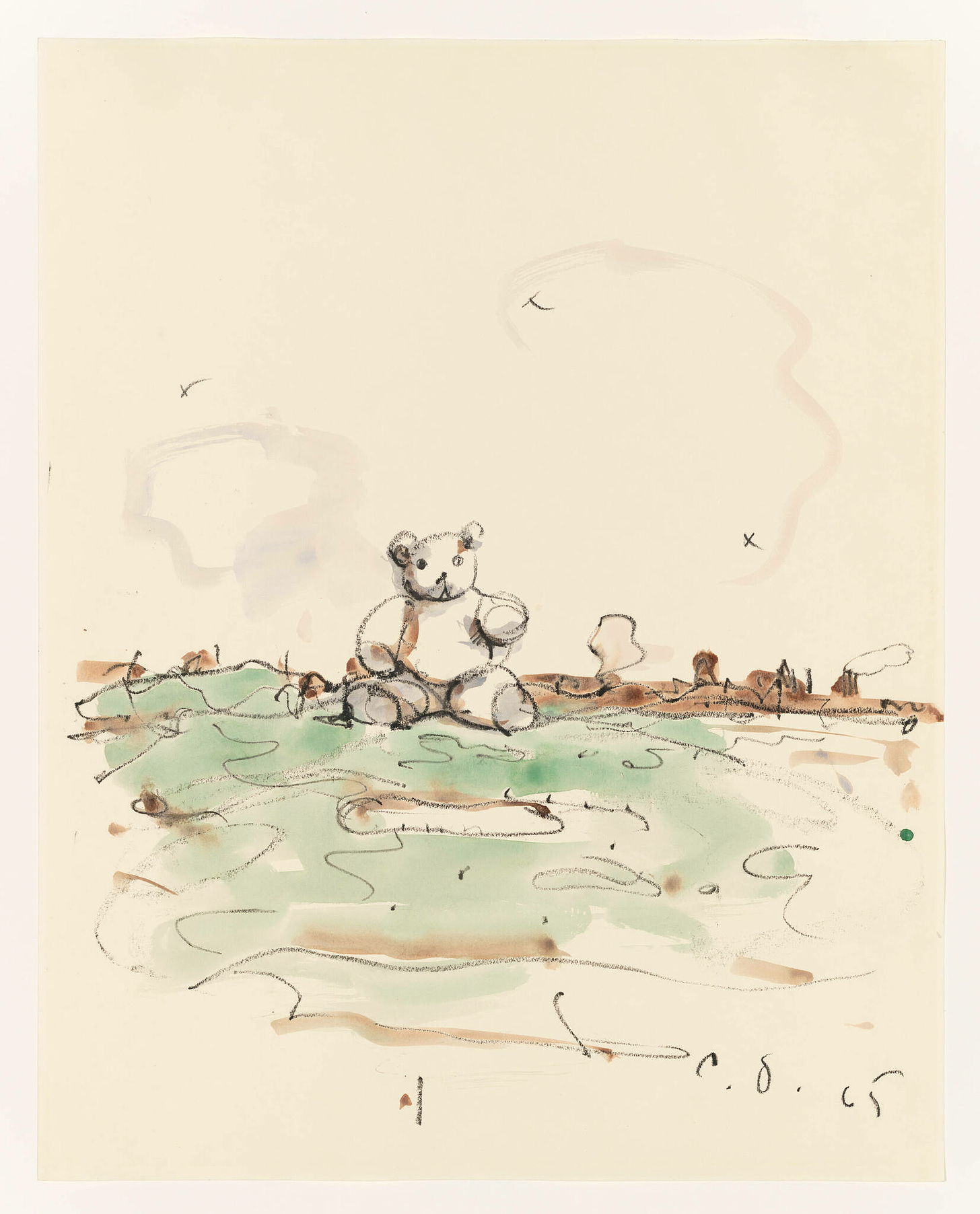

They included a giant teddy bear for Central Park, and a huge ice cream blocking up Park Avenue in Manhattan.

The monument Oldenburg proposed in place of the Statue of Liberty was an enormous rotating electric fan:

Oldenburg, who died in July this year at the age of 93, was one of the leading artists of the late 20th century. If you know his work it will likely be for the colourful oversized outdoor sculptures of everyday items situated in many urban locations around the world, which he created from the late 1970s in collaboration with his wife Coosje van Bruggen.

You might have seen photos of their giant shuttlecocks on the lawn outside the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, for example. Or the huge blue trowel at the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller in The Netherlands. Or the half-buried red hand saw at the International Exhibition Centre in Tokyo.

Their work is fun and playful, and it makes us pause and reflect on our place in the world; it makes us think about the everyday objects we interact with and take for granted in our familiar surroundings.

But there was nothing fun or playful about the proposal for the rotating electric fan monument. The Statue of Liberty represents the idea of America: a welcoming and safe nation driven by the principles of freedom, equality and opportunity. By replacing it with this particular object, an electric fan, in this particular location in New York Harbour where millions of immigrants had entered the country in the past, Oldenburg was suggesting a different idea about America in the late 1960s.

The recent Immigration Act of 1965 had adjusted existing restrictive laws which excluded individuals from certain ethnicities and had prioritised citizenship for white people from Northern European countries since 1790. In the 1960s, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, this long-standing discriminatory immigration policy was seen as a national embarrassment.

But polls showed that half of the public supported the existing system and that American opinion was split about who and how many people should be welcomed, and under what criteria. Concerns about jobs, welfare and national identity were at the heart of those debates.

Immigration was a hot topic then as it is now.

Oldenburg once said that art should ‘try to reach people and sum up what people are feeling and should try to make people all into one.’ His proposal for a giant statue of an electric fan at this symbolic entry point to the USA represented something perhaps a bit more honest or troubling than what the Statue of Liberty symbolised. Plenty of Americans embraced newcomers, but many were not welcoming of immigrants. Oldenburg’s fan suggested other feelings existed, that the picture wasn’t so squeaky clean and heartwarming. It seemed to say: let’s blow them away somewhere else, keep them out.

More than 50 years later that split in opinion towards immigration is still there. Recent debates in the States have focused on the influx of immigrants from central and south America, and on the question of whether to build walls and how to tighten up security along the southern border.

But this is not just an issue for the USA, and that’s why I think it’s such an interesting artwork. The movement of people in search of safety or the promise of a better future for themselves and their families is something all countries deal with around the world.

Oldenburg’s colossal statue of an electric fan would not look out of place on the south coast of England, for example, given current British policies on illegal immigrants attempting to cross the English Channel in flimsy boats. Blow them all back to France, it’s someone else’s problem! Or if they reach our shores, deport them to Rwanda immediately.

But it’s not someone else’s problem: movement of people is the reality of our global community and it’s an historical pattern.

Oldenburg’s artwork points to the history of debates around immigration and gives us a longer view on the issues embroiled in this subject: competing ideas about freedom of movement, economics, national identity and how to deal with humanitarian crises. It’s not an artwork that ‘takes sides’ on this issue. Rather, I think it challenges us to accept and discuss the complexities of it.

Although it’s not well-known, the electric fan is, in my opinion, one of Oldenburg’s enduringly relevant and thought-provoking artworks.

If you’re interested in finding out more about Claes Oldenburg, here are some rabbits holes to go down:

Lots of articles and images on the working relationship between Claes and his wife Coosje van Bruggen from Pace Gallery, which represents their estate. And an interesting 5 minute video about them.

A podcast episode from The Lonely Palette about Claes Oldenburg’s Giant Toothpaste Tube (1964).

Archival footage of Oldenburg talking about his practice (warning: he has a reputation for sounding a bit dour…) including more on the Proposed Colossal Monuments series.

Oldenburg has been a big influence on a younger generation of artists. Here’s a lovely video in which American artist Alex da Corte talks about his relationship with Oldenburg’s work, particularly his early sewn sculptures.

Oldenburg was a writer and an artist. Here is his most famous piece of writing I Am For… (Statement, 1961), sort of like an artist manifesto. The filmmaker Julian Rosefeldt used it as inspiration in one of his short films on artist manifestos from 2015, featuring the actress Cate Blanchett. The entire film series is essential viewing for any Blanchett fans amongst you. She’s that good.

3 Artists exploring the subject of the US-Mexico border:

Back in 2017 the French street artist JR developed a project where he pasted an artwork over the US-Mexico border at Tecate, and arranged a picnic on both sides of the wall, bringing communities together in dialogue and collaboration:

In 2005 the Argentinian artist Judi Werthein caused controversy in the media with the artwork Brinco (‘jump’ in Spanish). It was a sneaker brand designed to help Latinx migrants cross the border from Mexico into the United States. The project raised the question of why commodities could move easily between countries but the people who made them could not. Here she describes the trainers in a 3 minute video.

A thought-provoking 5-minute video from Minerva Cuevas, a Mexican conceptual artist who makes site-specific interventions for social change. She talks about how our perception of the US-Mexican border is about limits, control and violence, something that we’ve been primed to think through media coverage of it.

Love your voiceover, Victoria. There's so much here I hardly know where to start! I sort of know Oldenburg's work but it's interesting to hear about art he made that isn't widely known. It's quite political really when you think about it, which isn't how I think about his work at all. Good to get a long view on immigration when things feel so dire at the moment. I've got to get up now but I'm going to come back to this later. Looking forward to watching the Cate Blanchett video.