I was listening to a podcast this week about homelessness in Finland, and how they have largely eliminated the problem there. It’s a small country of just five million people, and back in the 1980s they had really high homelessness numbers. The government tried a radical approach to address the issue, which involved giving homeless people their own apartment with no strings attached.

Most other countries attempt to tackle homelessness with what’s called a ‘staircase model’, which is founded on a ‘treatment first’ philosophy. Homeless people are typically only placed into ‘normal’ housing when they exhibit evidence of what is called ‘housing readiness’ i.e. that they have demonstrated basic living skills, sobriety and a commitment to engage in treatment. Finland’s pioneering ‘housing first’ approach turned this model on its head, with the new premise being that if you sort out someone’s housing issues first then they can start to sort out the other problems in their life.

In 2007 the Finnish government funded a project to rent out apartments to homeless people at rates they could afford, which were covered by their housing benefit. Shelters were converted into single units with a communal space, and support was available 24/7 for as long as the tenants needed it. In this affordable supported community, people can learn new skills like growing and making food for the shared kitchen, and they are helped to find jobs in the local neighbourhood. This support is what stops many tenants from falling back into homelessness. It has been a huge success, with just one in ten tenants becoming homeless again.

There was of course a big investment outlay at the start because they needed to convert shelters into individual units, and then train up support workers. But the cost savings now are 15,000 Euros per person every year because tenants are no longer drawing on expensive emergency services from the police and the health sector, and very few now end up in prison. Some of these people become completely independent again, although others need support for the rest of their lives. What I loved about this story was the acceptance in Finland that that’s ok, and is the reality of complex societies in which we collectively provide a safety net for the most vulnerable.

I wonder how this sort of policy could work here in the UK given that there still exists a strong current of Victorian sentiment focusing on individual responsibility as the solution to poverty, and that people who draw heavily on social support are ‘lazy scroungers’. So I was pleased when I googled ‘housing first’ to discover that there are in fact pilot schemes in a number of locations in England and Scotland.

But a different kind of homelessness is now emerging here because of government policies over the past few years that have led to a chronic shortage of affordable housing and steeply rising rents. The profile of people who are losing their homes is moving beyond those who would usually be perceived as most at risk. Increasing numbers of individuals and families can no longer keep afloat with the rising cost of living. They can’t make the rent, no matter how many hours they work, end up getting evicted and then can’t find other affordable accommodation to move into. The problem is particularly acute in London.

Local authorities in the UK have a legal obligation to help homeless people find shelter, which is increasingly hard to source. Many have been put up in ‘temporary’ accommodation such as hotel rooms and BnBs, and end up staying there long-term. Meanwhile, charities have been warning that food banks are at breaking point with millions using the services every week. Something is going very wrong in our system when so many people find themselves in such a precarious position that they can no longer cover the basics of food and shelter. ‘Housing first’ isn’t the solution for this variety of homelessness.

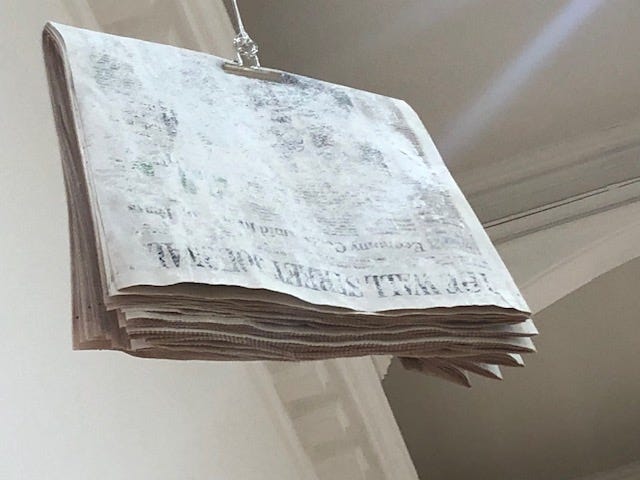

Yesterday as I was walking around the exhibition of work by the American artist Pope L. at the South London Gallery, I was struck by how much his art resonated with these issues. The exhibition is called Hospital, and in the main gallery there is a huge sculptural installation which looks like some sort of dystopian ruin. It is a towering mess of tangled wood, old plastic bottles, newspapers, broken fishing rods and overturned toilets dangling precariously in mid-air, all covered in a white powder, accompanied by amplified creaking sounds and the smell of alcohol. On the walls a sticky brown liquid is dripping down from glass bottles on shelves. The structure looks ready to fall, like it is on the point of collapse. And in my mind, with all the stuff on homelessness I’d been thinking about this week, it felt like a sign o’ the times.

Pope L. (1955-2023) was a multidisciplinary artist (writing, painting, performance, installation, video and sculpture) and although he isn’t a household name with audiences, his influence on other artists over the years has been profound. He died last month aged 68. Back in the late 70s he started to make a reputation when he did a performance called Crawl (1978). In this work he dressed himself in a cheap suit bought from a charity shop, sewed a yellow square on his back, and crawled the length of 42nd Street in New York on his hands and knees. Passers-by were forced to confront the incongruity of a man in a business suit crawling along the busy sidewalk.

It was a genius performance, which drew attention to the homeless people that the average upright citizen walking along the street often tries to ignore. And it probed assumptions about race, poverty, and how we should and shouldn’t behave in public space. At the time several of Pope L.’s close family members were living on the streets. Afterwards he described the response he got from onlookers and the police, who had tried to move him on. He said,

People got pissed off because I’m black. If you’re not drunk, if you’re not ill, if you’re not crawling to Jesus, what are you doing?

It was uncomfortable to watch, and it got right under people’s skin in the way that only the most powerful art can.

He repeated Crawl several times over the years and the meanings shifted in different contexts. This is the way in which Pope L. worked throughout his career, creating what he called ‘families’ of artworks. Hospital is part of a family that started back in 1991 when he did a performance called Eating the Wall Street Journal. It was in response to an advertising campaign that suggested that a subscription to this American business newspaper would bring you great wealth. You didn’t even need to read it.

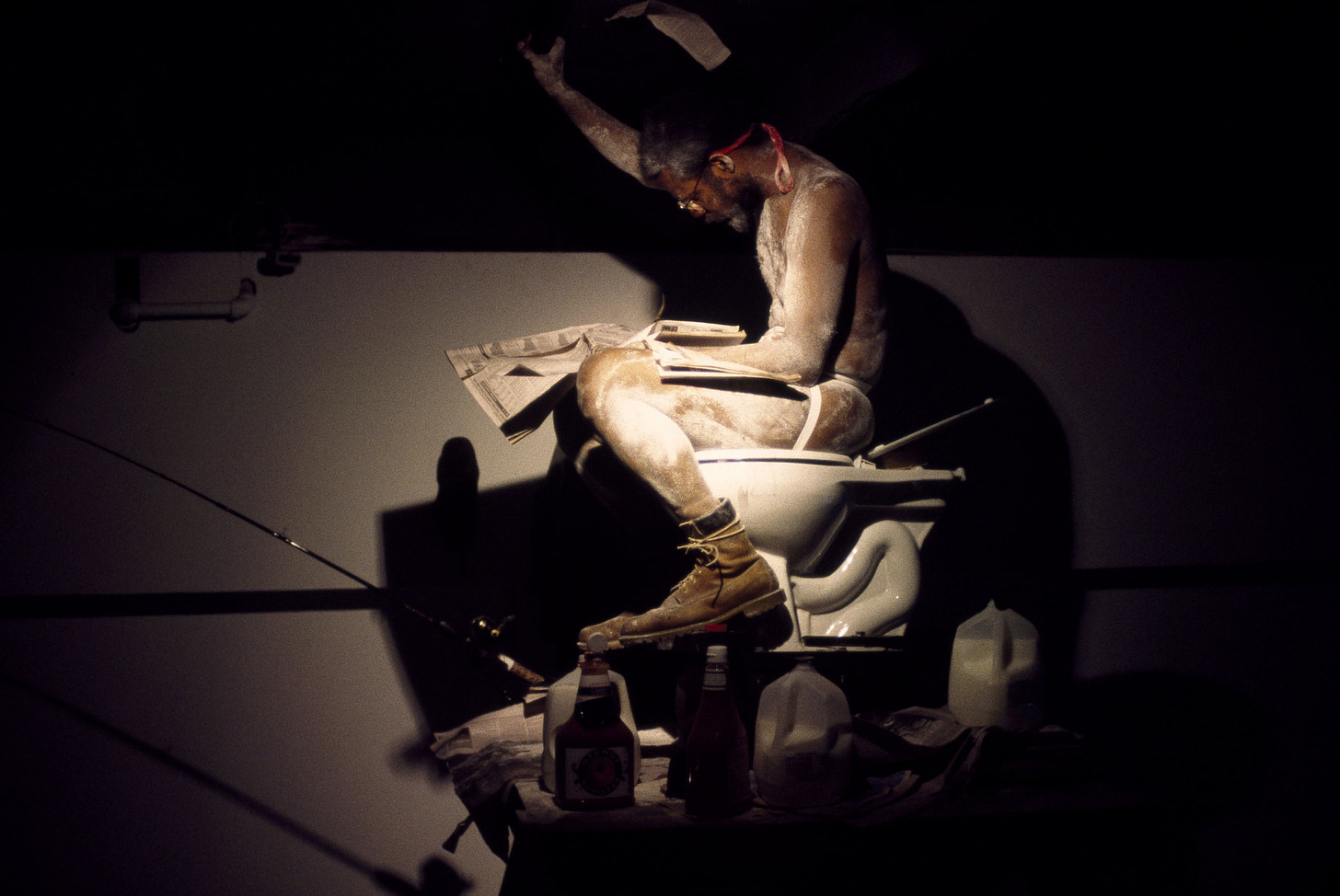

Taking this assertion to its absurd conclusion, Pope.L created a series of performances in which he ate pieces of the Wall Street Journal whilst sitting on a toilet on top of a tall wooden tower, wearing just a jockstrap and doused in white flour, a manufactured and consumable form of whiteness. He added milk to lubricate his chewing in an attempt to ingest the wealth that the advertising promised. The work was a critique of capitalism, and the systemic inequities that shape the lives of the disenfranchised.

In this version at the South London Gallery the context and the meanings have changed from these earlier works. Pope L. himself wasn’t performing, but he intended the materials to do that performing instead. The huge wooden structure is teetering like it is about to give us its final dramatic act of collapse. You might read it as a metaphor for the systems in our world that we are told are on the verge of collapsing too — not just the housing system, but capitalism itself, democracy, and the delicate balance of the natural world.

None of it has collapsed yet though, and there’s something quite playful about this particular piece. My young gallery companions quickly spotted the bowl of flour and the invitation to grab a handful and chuck it over the installation. Perhaps it was Pope L.’s suggestion that we have some agency still in all of this, and that we can make change happen.

I think his work is really interesting and layered with lots of meanings. There’s no easy or clear reading of his work; it doesn’t give you immediate answers. It’s not pretty and it’s not comfortable. But if you stay with it for a while it gives you a feeling of something that sort of makes sense, if you know what I mean. And that’s the kind of art I really connect with.

As always, Gallery Companions, I’d love to know what you think about Pope L.'s work and any of the ideas I’ve talked about here.