Who Controls the Narrative?

Art, storytelling and conspiracy culture

Listen to this as a podcast on Spotify or Apple, or search for The Gallery Companion on your podcast player.

I’m running a bit behind schedule this week because I was in London for the Independent Podcast Awards this past Monday night. The awards celebrate all those small indie podcasters who don’t have mega-budgets, or production companies behind them, or celebrity hosts. It’s for people like me who lovingly create content in our spare time, recording episodes huddled under the duvet for better sound quality.

I was absolutely thrilled that The Gallery Companion made the shortlist, and it was a real buzz to have that validation from the podcasting industry. Every week the number of people following my podcast ticks up, and it’s really exciting to see it grow. So thank you for listening and please please recommend it to other people you think will enjoy it. Word of mouth is the secret sauce for finding new audiences.

This week I want to talk about a really interesting book that I’m reading at the moment by the Canadian author Naomi Klein. She’s a journalist and activist, and Professor of Climate Justice at the University of British Columbia. I’ve loved Klein’s work ever since her first book No Logo came out back in 1999, in which she explored consumer culture and branding, investigating the ways in which Big Business exploits workers in third world countries in pursuit of profit. It was such a brilliant critique of globalisation and the way in which late capitalism functions that Nike, one of the companies she focused on, had to move into damage-limitation overdrive and issue a point-by-point response to protect its reputation.

Klein’s new book Doppelganger is a fascinating dive into the online underworld of conspiracies and misinformation, a subject which has become increasingly visible in the wider public consciousness since Covid (here’s a really interesting recent podcast from the BBC about conspiracy theories, for example). The starting point of the book comes from her experience of frequently being confused with the feminist author and now mega conspiracy theorist Naomi Wolf. They are both journalists, they are both Jewish, they are both around the same age, and of course they are both called Naomi.

But Naomi Wolf, whose breakout book The Beauty Myth was first published back in 1991 to wide acclaim, has been going down some dark rabbit holes in recent years. She’s now almost a daily guest on the podcast War Room, hosted by Donald Trump’s former advisor, the right wing political influencer and Conspiracy-Theorist-in-Chief Steve Bannon. Earlier this year research from the nonprofit public policy organization The Brookings Institution crowned Bannon’s show as the top peddler of false, misleading and unsubstantiated statements from Apple Podcast’s list of the 100 most popular political talk shows.

Having a doppelganger whose reputation is for spreading batshit crazy conspiracy theories both alarmed and intrigued Klein. And in true investigative style, with the grace and sophistication she has for weaving together facts and concepts into words that make sense and motivate, her book takes you on a journey into conspiracy culture.

The three most popular subjects for conspiracy theories at the moment are climate change denial, election fraud, and various stories about the Covid pandemic. But they all have the same basic ingredients. There are baddies at the heart of all of them: the hidden villains, the ‘elites’ controlling everything behind the scenes (for QAnon conspiracists these days it’s a cabal of satan-worshipping paedophiles operating from the basement of a pizza restaurant in New York). Then there are the victims: the people who are being taken for a ride and being fooled by these evil people. And finally there are the heroes who have figured out the truth, who are going to save everyone, and who are working to unmask the baddies and bring them to light.

Conspiracy theories are powerful because they mix grains of truth with make-believe and out-and-out lies. The most effective ones are examples of compelling storytelling that have the potential to reach our implicit biases and to rile us up emotionally. As Klein says,

conspiracy theories often get the facts wrong but get the feelings right — something is being hidden from us, something doesn’t add up, there is impunity for the powerful.

It’s good to have a healthy scepticism about those in power, because power corrupts, and corruption very frequently goes unchecked. But this healthy scepticism can tip into something more sinister that we collectively need to combat. We are yet to see the results of the massive battle underway in the USA in defence of democracy and the rule of law with the legal cases piling up against Donald Trump. He is the ultimate storyteller with a sing-song voice, a shrewd political operator whose nonsense constantly taps into conspiracies, spreading hate and division, and scapegoating certain groups of people. It’s unlikely that Trump actually believes the lies he peddles, but he has certainly worked out that he just needs to sow enough doubt to make people question what the truth is. When that is to question the structures of democracy itself, we are in really dangerous territory.

We’ve seen this happen throughout history when charismatic leaders and politicians understood that power lies with those who can control the narrative. It’s exactly what happened in Nazi Germany in the 1930s. Hitler blamed the Jews and the Communists for social and economic problems in Germany that were in fact systemic with deep historical roots, and he led a destructive narrative from the top with persuasive storytelling and misinformation.

But conspiracy theories are ultimately a distraction. They allow people to look away from the unbearable realities of our world: the horror of war, the injustice of social inequality, the frightening prospect of climate change. They thrive amongst the discontented, the anxious and the marginalised, who turn to them to explain away problems that are actually a result of economic and social structures and systems that are complex and hard to understand, or that involve us facing up to inconvenient truths.

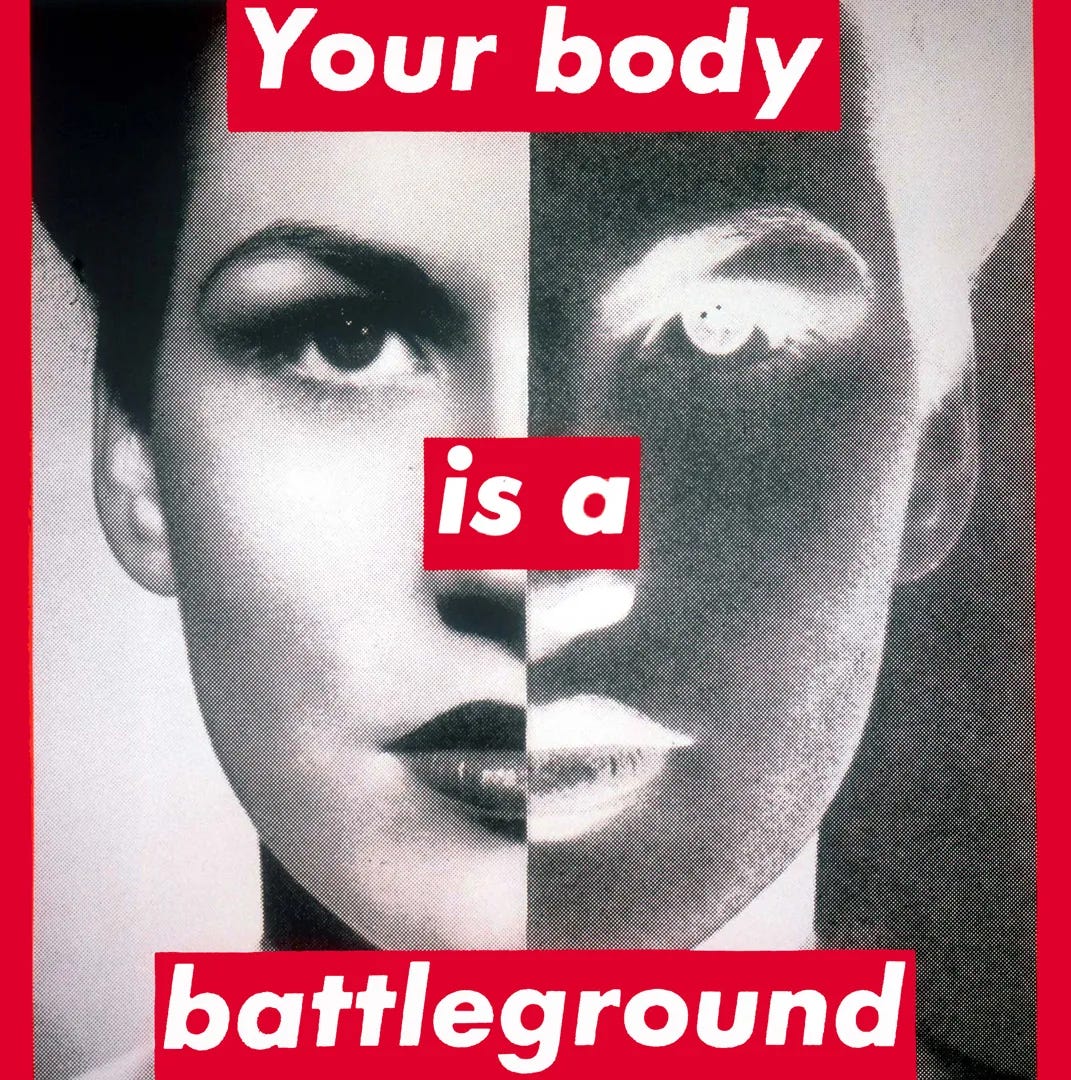

As Naomi Klein says, ‘all of this is about not seeing’. As I have been reading her book I’ve had that image by the American artist Barbara Kruger in my mind, The Future Belongs to Those Who Can See It from 1997 (image above). It’s a black and white close-up photo of a woman’s face in profile looking upwards, with a hand above her eye holding a pipette. Kruger is one of the leading artists of our generation, and it’s likely that you’ve seen her work circulated on social media. Probably her most famous artwork is Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground), which she produced for the Women’s March on Washington in 1989 in support of reproductive rights. It was resurrected and went viral last year when the US Supreme Court voted to overturn longstanding abortion legislation.

Kruger’s work is all about holding power to account, questioning what we think we believe, and what we read in the media. Her signature style is white text on a red background, as though she has cut out headlines from a magazine, which she pastes on top of black and white photos, putting together ideas and images that don’t sit comfortably for the viewer. There’s something a bit uneasy about The Future Belongs to Those Who Can See It. For me it is both sinister (what is being dropped into the woman’s eyes exactly?), and it’s a call to be clear-eyed. To keep questioning what we see, to think about who or what is feeding us the narratives we hear, the images we look at, the messages that we consume in the media on a daily basis and for what purpose. It suggests that those who understand what’s going on have a better chance of influencing what will happen - for better or for worse.

There’s a difference in the speed and reach of conspiracy theories that circulate now compared to the past, and it’s due to the new Attention Economy that dominates all of our lives. That’s one of the many interesting layers that Klein discusses in her book: she asks who benefits from our addiction to social media and the information we all incessantly consume on our phones? These platforms have incentive structures that monetise the most clickable content, and that in itself drives creators to make more and more wild and salacious conspiracy claims.

The democratisation of content creation and the ease with which we can all learn to use readily available software to produce eye-catching videos and images, has led to the proliferation of noisy distraction on social media. And they come thick and fast. If you’ve been on instagram and watched that cute dog dressed up as a postman delivering parcels, within no time you’ll have watched ten videos of dogs dressed up in halloween outfits or as contestants in beauty pageants. They are so addictive that you don’t even know it is happening till you’ve been doing it for a solid half hour. If your algorithm has got you marked as an anti-vaxxer or a climate change denier you’ll quickly be led down those rabbit holes. They are designed to prevent us from seeing information that is likely to challenge our beliefs, and to connect us with people who share similar ideas. If you like this, then you will like this. Keep watching, keep consuming. Because that’s how the companies make money.

This is the subject of a brilliant film by the American photographer Cassandra Zampini, whose work examines the role of media in shaping our understanding of the world and our place within it. In her 25 minute work Media Warfare (2020) the New York-based artist downloaded and compiled hours of conspiracy theory videos from the internet. It’s not hard to find this content: just follow a hashtag like #GreatAwakening or #SecondCivilWar. Zampini’s film is compelling viewing, as one video quickly replaces the next, giving us a window into the madness of these conspiracy messages. Just like with the videos of cute dogs on my instagram feed, I was totally sucked in and hooked by it. It’s an artwork that perfectly mirrors our online experience of algorithms, and one that speaks of the sheer volume of misinformation circulating in plain sight.

But what to do about all of this disturbing stuff? Some people argue that it’s about holding media companies to account, making them do better on content moderation and fact-checking. But as Zampini says, even when videos are censored they quickly pop up elsewhere. They get shared and reposted, out of anyone’s control.

Naomi Klein has another solution, and one that is more realistic in my opinion: education. She argues that we have to talk more about the systems and structures in our world that are causing inequality and leading us down the road to environmental catastrophe: capitalism, patriarchy, imperialism etc. And then we need to get organising collectively to solve the real problems and to bring material improvements to people’s lives. It’s all about finding political solutions.

Part of this necessary and urgent education is to raise awareness and understanding of the way in which the media operates and for whose benefit. We’ve got to constantly question orthodoxies and interrogate the beliefs that we hold. When I think about this subject my mind often goes to the work of the South African artist William Kentridge. He makes short animated films that, like Barbara Kruger’s work, ask us to question what we think we know and understand.

At one level you can read Kentridge’s films as a crushing commentary on the white supremacist politics in the apartheid era. His film The History of the Main Complaint (1996) was a response to the public testimonies heard in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings which investigated the atrocities that occurred in South Africa. In this short clip Kentridge talks about the ideas in this particular film, and it gives you a sense of what his animations are like:

But there’s meaning on another level in all of Kentridge’s films, in the philosophy behind his process of making art. He constructs his films by drawing on paper using charcoal that he then photographs before rubbing out part of the drawing and changing it slightly, rephotographing it, rubbing it out and redrawing again, and so on. It’s a laborious process, which Kentridge calls ‘Stone Age film-making’. His films remind me of early black and white Mickey Mouse cartoons in which you can really see the labour of the artist’s hand in the unpolished animation.

That hand-made process creates an uncertainty in the line of his images and a constant shifting of views in the film. I don’t know how to express the experience of watching it other than to describe that uncertainty as palpable. Kentridge has talked about how he is interested the process of how we think, how we take fragments and re-interpret them retrospectively to make sense of the world. Back in 2014 he said this:

Uncertainty is an essential category. As soon as one gets certain their voice gets louder, more authoritarian and authoritative and to defend themselves they will bring an army and guns to stand next to them to hold. There is a desperation in all certainty. The category of political uncertainty, philosophical uncertainty, uncertainty of images is much closer to how the world is.

Conspiracy theories offer certainty in an uncertain world. People like Donald Trump use them to distract from real problems that he offers no solutions for, to make money from his followers, and to maintain his grip on power by undermining faith in our democratic institutions and processes. So I’m all for embracing uncertainty and trying to encourage others to think like these artists who question the dynamics of power, because the nightmarish alternative cannot be our future.

As always I’d love to know your thoughts on any of these artists and ideas so please click on the comment button below to leave a message.

Join The Gallery Companion’s Patrons!

As a patron of The GC you become part of a private conversation space where we talk about the art we’ve seen recently, share images and links to interesting stuff, and discuss ideas together. It’s kind of like a group chat or live hangout for my VIPs. Plus the occasional meet up IRL.

In the chat thread this week, I’ve shared some thoughts on the Philip Guston exhibition at Tate Modern in London at the moment. This particular travelling show has had a difficult ride over the past few years because some of Guston’s paintings from the late 60s feature cartoon-like images of the KKK. It was postponed by a couple of museums in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and the BLM protests. Subscribe for just $5 per month and join the conversation!

Such a thought provoking topic. I hadn’t considered art’s role in exposing and investigating conspiracy theories. The Klein video is quite powerful as well. There’s a lot of Freud’s Uncanny in this post.

Congrats on the award shortlist! Such a huge accomplishment. 🎉

Congratulations on being shortlisted.

I'm interested in reading Doppelganger now, having read your review.

I hadn't heard of the people you refer to, apart from the two Rachels of course, but I hope to explore further.

What I find intriguing about conspiracy theories is how the people who promulgate them believe themselves to be immune, which means in effect that THEY are members of an elite! How ironic, and rather a pity that the irony is lost on them