Confessions of a Would-Be Art Toucher

Plus Frank Bowling on colour, Gombrich's Story of Art, horse sculptures, and more!

2025 is nearly over, Gallery Companions. It’s been a funny old year in my life with lots of deep tectonic shifts. But one of the highlights for me was getting back to regularly writing this newsletter, and feeling like I’ve got stuff to share that people want to read. Thanks so much for opening these emails, commenting, liking and sharing. I appreciate you.

I’m really excited for 2026, and I’ll be announcing some new projects I’m developing in the new year. Meanwhile, this last missive from me this year is a pick-n-mix of all sorts, including:

A recent discovery of an English sculptor that I would love your opinion on.

An exciting, multi-sensory exhibition that invites visitors to look, listen and touch, challenging the idea that art is only meant to be seen

A feast of links, videos, quotes, thoughts and images for your contemplation.

And my list of must-see exhibitions this week.

One more thing, if you want to hear more from me, my social media posting place of choice is Substack Notes. I find it to be a much quieter, slower, more engaging, rewarding space to be in than most others. A space for conversation rather than endless, rapid scrolling. I share videos and images, my thoughts on art and other things, and interesting Substacks on there most days. If that sounds up your street you’ll need to download the Substack app if you don’t already have it. I wish more artists would tbh.

If you celebrate Christmas, have a very happy one! I’ll be back in the New Year.

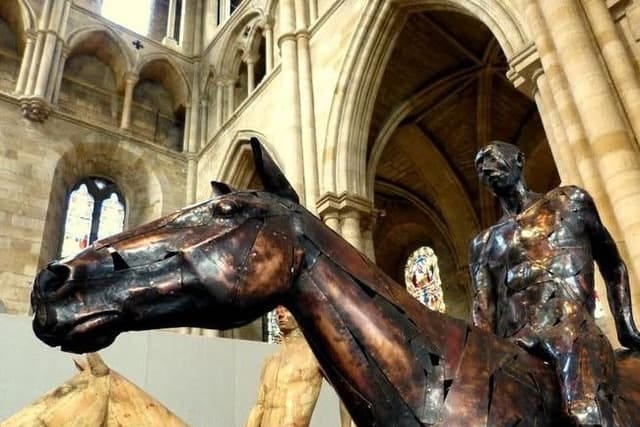

In Praise of the Quiet Sculptor

I recently discovered the work of Harold Gosney (born 1937), a sculptor who comes from the North of England, near Grimsby. He’s got a show on at York Gallery at the moment, which is how he came across my radar. Gosney is one of the many unsung artists of our generation — part of the vast majority who never reach the mega-gallery stratosphere, but instead keep quietly working, teaching, experimenting, and steadily building a practice over a lifetime. He’s my kind of artist.

Gosney’s work is rooted in figurative tradition and craftsmanship, and he’s perhaps best known for his sculptures of horses.

This video of Gosney discussing his long career and influences captures how an artist gradually accumulates layers of knowledge over time. I love watching him get his tools out to show us his process of making, working bits of wood, stone and metal by hand. It’s a delight to see the materials come alive in his process. Gosney also shares how drawing influences his practice, revealing his determination to understand each object completely before sculpting — which is, for him, the thrill of sculpture.

Plus there’s music in his art. He’s a self-taught classical/jazz musician, and is really engaging on how the crossovers between the artistic forms inform his understanding of three-dimensionality. This cross-disciplinary process is a subject I’ve written about before.

I’d love to know your thoughts on Gosney’s work and the ideas he talks about. There’s something so wonderful in listening to the joy he gets from making art:

Touching taboos

Not touching art in museums is important for the preservation of the work, but I often find myself wishing I could get my fingers onto Van Gogh’s painterly surfaces, or feel the cold and contours of Degas’s little bronze dancers. Just to really understand the piece, you know?

So this is very exciting: an exhibition where you can look AND feel. For people who are all about the haptic — knowing through touch — this will be an interesting experience. A new show at Henry Moore Institute in the UK, Beyond the Visual, challenges the dominance of sight in how we make and relate to art, inviting visitors to experience it using all the senses.

Designed with blind and partially sighted visitors in mind, the exhibition brings together historical art (some lovely pieces by Henry Moore included) with contemporary artists.

Serendipitously, MoMA just put out this thought-provoking video on the challenges they face in keeping roving visitor hands separate from precious artworks. Some art you can interact with physically, which makes that task all the harder: conceptual artists since the 60s have actively encouraged audience participation in artworks. Yoko Ono was a pioneer in breaking the ‘don’t touch’ taboo of museum artworks:

Have you ever felt the urge to touch a work of art to understand it better? If touch were allowed, which artwork would you most want to experience with your hands? Let me know in the comments!

Other bits and bobs I’ve been watching, reading and enjoying

It’s all about colour for Frank Bowling, the British-Guyanese abstract painter. And oh my gosh, what colour! He’s 91, can hardly stand, but is excited to get into his studio every day to make work. I really enjoyed the interaction between him and his studio hands in this recent video:

In case you ever wonder what’s relevant about early 19th century paintings today, here’s some great chat from contemporary artists on the landscapes of J.M.W. Turner and John Constable in the age of climate change, in this video from Tate Gallery.

Sad news of the death of Martin Parr, Bristol-based photographer who spent his career sharply observing consumerism, social class, taste and national identity, particularly in Britain. I’ve had to rewatch this half-hour documentary on his oeuvre just to get my fill again. So good. There’s another more recent documentary but you can only watch it for free if you have access to BBC player. And amidst all the glowing obits, here’s a deeper analysis of Parr’s work from Ocula Magazine on how his work forced viewers to confront the ways we judge and categorize others based on appearances. His photographs are never neutral: they record both what people do and how they are seen, exposing the social and economic structures embedded in ordinary life. Worth a read.

What a way to start an essay:

I first met Giacometti when I was married to Marc Riboud, a photographer who was a protégé of Henri Cartier-Bresson. It was 1962, and I was a young bride—a baby, really. They were close friends, and once, before Marc left on a trip to Vietnam, he said to Henri, “Take care of Barbara. She doesn’t speak a word of French.” Cartier-Bresson said to me, “Let’s go to Giacometti’s studio. Have you ever met him?” And I said, “Of course not.”

This is a fascinating read from Ursula Magazine (from Hauser & Wirth) on the sculptor Barbara Chase-Riboud’s memories of Alberto Giacometti. It’s a different age, a different world, a different Paris, recounted by someone who still remembers it.

Imagine finding an old Rembrandt original in a drawer. For goodness sake. Would you sell it?

Some excellent observations and advice for artists on the importance of having a clear work ethic to make it in the artworld from Blackbird Rook, an independent gallerist and art advisor, who also writes a great Substack. He says:

making good art is not the same as making it as an artist. Those are parallel, sometimes conflicting, vocations. The studio trains one set of muscles - discipline, invention, solitude. The art world demands a different set entirely: clarity, legibility, stamina, and the peculiar social agility required to be remembered. Not because the game is noble or even particularly rational, but because art only matters once it leaves your hands. If you want your art to be more than therapy then it must find advocates, interlocutors, collectors, critics, and the support structures that allow it a life in public view.

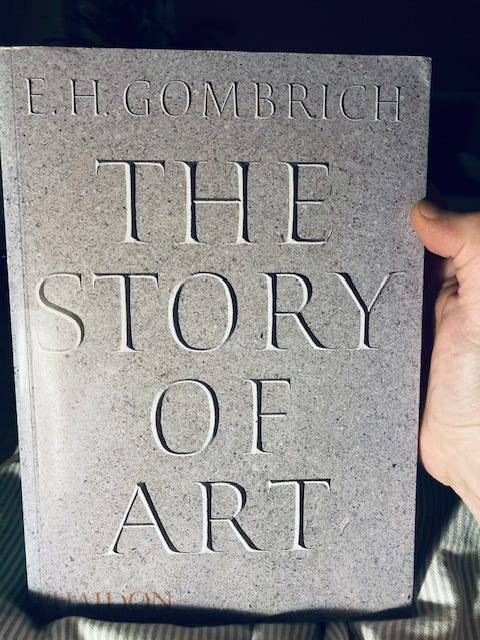

I’ve decided to start reading this big old tome again, with fresh eyes, in 2026. Haven’t read it with sustained attention since I was 19. That’s nearly 20 years ago. What an intro to art history! Somehow I thought it was a good idea to take it with me backpacking around Europe, despite it being quite weighty. My back was in better shape then. Even though there are more canons, branches and artists than this one story suggests, Gombrich’s strength was in training readers to see art as problem-solving: how artists dealt with space, light, the body, emotion, and meaning. Have you read it, what impact did it have on you, and who’s up for reading it with me in 2026?

Three exhibitions I’d like to see

Monument to the Unimportant, Pace Gallery, London, until 14 Feb 2026. Bringing together artists including Oldenburg, Thiebaud, Whiteread, Hockney and Fischer to show how the most ordinary things — cakes, pipes, weeds, household objects — can be turned into the playful, poignant and powerful.

Joan Semmel: In the Flesh, The Jewish Museum, New York, until 31 May 2026. Exploring the body, intimacy, ageing and female autonomy across more than fifty years of her practice. Unmissable. I’ve written about her here. And here’s some excellent chat about her on the Week in Art podcast this week.

Limitless Drawings: Masterpieces from the Centre Pompidou Collection, Grand Palais, Paris, until 15 March 2026. Another group show, and this one sounds like a corker. 300 artworks exploring the ways in which drawing is endlessly being reinvented. Its scope includes works on paper, murals, installations, photography, film, and digital technology by Balthus, Basquiat, de Kooning, Giacometti, Man Ray, Brice Marden, and Picasso amongst others. Eurostar here I come.

That’s a wrap for 2025, GC readers.

Let me know your thoughts on anything and everything here! And please help me spread the word about this newsletter by clicking like or restack. Or better still, share it with someone you think will enjoy it.

Thanks for reading!

I decided I’d really like to touch—pet—the horse sculptures.

What if every new artist made one piece in their exhibition just for touching? We could watch the wear and patina, satisfyingly.

I can certainly relate to the urge to touch ( or smell, or eat! ) the pieces we find very engaging. I have never questioned the practice of touching with our eyes and being moved to make something as wonderful as that piece or the next. Although I don't expect to start physically touching the surfaces but the thought is rich with mystery.