Art for the Tech Bro Era

Plus Venice Biennale fury, AI murals, David Hockney and more!

This week in The Gallery Companion:

There’s anger at the choice of artist for the US pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2026. But is it justified?

KAWS at SFMOMA. An example of red-chip art. Like blue-chip but hollow and really hot-commodity.

Plus a mysterious AI mural in London. Who, what and why? And more importantly, is it interesting or good?

And my list of must-see exhibitions this week.

Deeply dispiriting art?

This week the largely unknown artist Alma Allen (I’m afraid I can’t point you to his website as he doesn’t seem to have one) has been announced as the choice to represent the USA at the Venice Biennale in 2026. The Biennale is the Olympics of the art world — a sprawling, century-old exhibition where countries send artists to represent their national identity on a global stage. The national pavilions carry huge symbolic weight: they are part cultural diplomacy, part artistic bragging rights, and part weather vane for what each country wants the world to think it cares about.

Allen’s work is characterised by large-scale organic, biomorphic sculptures in wood, marble, volcanic rock, and bronze, shaped by a mix of hand-carving and modern digital techniques. I’ve never seen any of Allen’s work in person, but critics have described his art as having the rare quality of feeling both ancient and contemporary, grounded in material but full of quiet energy and life.

Describing the choice of Allen for the Biennale as ‘deeply dispiriting’, the Senior Editor at ARTnews took aim at the Trump administration:

This is disappointing, not because Allen’s work is bad (there are plenty of worse choices), but because the work has nothing to say about the state of our country at the moment. Perhaps this isn’t surprising. The US State Department runs the proposal process, so no one would expect a pavilion about crackdowns on migrant communities, rampant racism and transphobia, isolationist economics, censorship of the arts and the press, and a President who has been credibly accused of being a fascist. And the newly created nonprofit body responsible for funding the pavilion — the American Arts Conservancy — appears to be stocked with Trump allies.

In other words, Allen is being judged not on the quality of his work, but on its perceived political relevance, or lack thereof. And furthermore, the work’s failure to overtly critique the current US administration. The implication is that Allen’s art is conservative and safe, and the US pavilion is likely to present an apolitical, aesthetically neutral image of America, sidestepping the country’s pressing social and political crises.

But to court controversy for a moment, this angry backlash over Alma Allen’s selection made me roll my eyes. The criticism circles around these points: he’s a white male, he’s not waving an obvious political banner, he’s not the ‘right’ kind of symbol for the culture-war moment. It’s an argument that assumes a national pavilion must always be a referendum on identity politics. But once you step outside that narrow frame, Allen starts to look like an unexpectedly strong choice — maybe even a refreshing one.

Because if there’s one thing Allen isn’t, it’s an establishment insider. His whole biography pushes against the perceived notion that the art world only uplifts its own. He’s the definition of self-made: left home early, didn’t go to art school, taught himself everything he knows by working with whatever he had, sold work from the back of his truck, spent years making things in relative isolation, and quietly built a language of form without the gloss of big institutions or galleries supporting him.

The fact that he’s only recently hit wider visibility isn’t proof of privilege — it’s evidence of how long and how hard most artists work before anyone pays attention. He represents the 99% of artists who slog away outside the spotlight, not the curated few groomed for biennales since graduate school.

And maybe that’s the real political message here, even if it’s not wrapped in the language people expect. Allen’s work — slow, intuitive, grounded in labour and in listening to materials rather than ideologies — offers a counter-story about American creativity. It’s not about branding identity; it’s about building a life through persistence, instinct, and a refusal to quit even when no one is watching. The hard graft of making art is a subject I’ve written about before. Choosing Allen signals that the US pavilion can champion unknown artists whose work demands quiet contemplation. He’s an unlikely choice from the margins, but that’s precisely what I like about this selection. In a climate obsessed with optics, that feels like a far more radical gesture than the outrage gives it credit for.

Art for the tech bro era

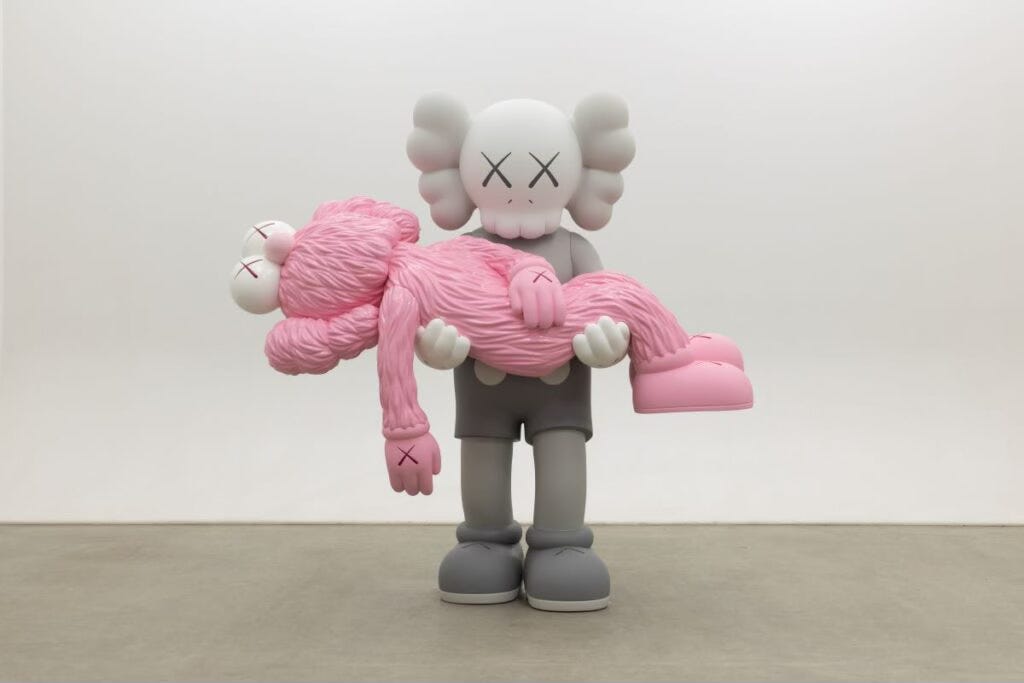

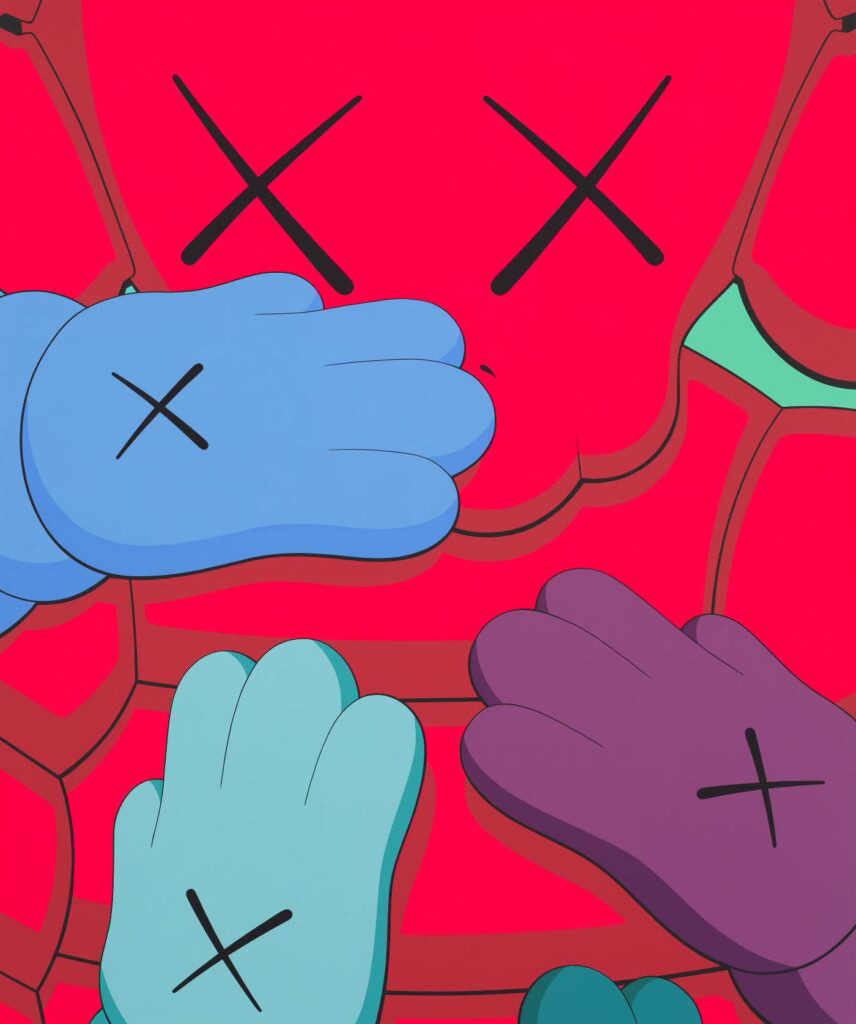

Moving swiftly on to other art which has been slammed as empty, this time with perhaps some justification. The American artist KAWS (aka Brian Donnelly) currently has a survey show KAWS: FAMILY at SFMOMA, which surprised me at first since he’s a bit more toy-store-pop-phenomenon than museum heavyweight.

KAWS is known for his cartoon-inspired characters, X-ed out eyes, and slick, pop-culture-infused sculptures. Starting out as a graffiti artist who subverted advertising posters, he moved into toys, fashion collaborations, and large public sculptures that blur the line between street culture and high art. His work is instantly recognisable, hyper-marketable, and hugely popular worldwide, though it’s often criticised for being more about branding and commercial appeal than deeper artistic or political engagement.

In truth it is all pretty vacant, derivative stuff (his forerunners were Andy Warhol, Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons). In this rather acerbic review of the exhibition in Hyperallergic, his work is summed up as ‘art for the tech bro era’. It’s an example of what has come to be termed ‘red-chip art’ — in other words art which explodes in value thanks to aggressive gallery backing, social-media buzz, celebrity collectors, or speculative flipping. Rather than having any sustained critical depth or museum-level significance, red-chip art is often glossy, accessible, pop-culture adjacent, and easy to sell. It’s art made for the market moment rather than the ages.

The vapidity, however, is precisely what’s interesting to me about KAWS’ work. There ain’t no quiet contemplation of deeper meanings here. And yet it’s so popular. Queues have extended around the block for tickets to this show. Why? For a start it reflects a broader desire among institutions, brands, and collectors for work that is culturally legible, easily marketable, and detached from any challenging social questions. In other words, it’s safe and accessible. No thought required.

But perhaps more significantly it reflects the state of the global art market, which has become increasingly financialised, favouring works that can function as stable, brand-like assets. In this climate, easily recognisable, influencer-friendly aesthetics are more attractive because they translate smoothly across international markets and social media ecosystems, reinforcing demand. Depoliticised, instantly legible art thrives precisely because it fits the structural logic of the market.

His fans will no doubt drop a shed load of cash in the gift shop, and this might go some way to explaining why SFMOMA have hosted the exhibition. Now that really is deeply dispiriting.

Brueghel-inspired nightmarish AI mural

I’m always on the look out for AI art that is actually interesting. A sort-of-Christmassy, mysterious public mural created using AI and recently put up in a London suburb, has been causing a stir with local residents. Click here to see and read more. I’m sort of intrigued by it. What do you think — interesting or not?

Three exhibitions I’d like to see

David Hockney: Some Very, Very, Very New Paintings Not Yet Shown in Paris, Annely Juda Fine Art, London, until 28 Feb 2026. Playing with colour, perspective, space. It’s homage and reinvention from Hockney. 88 and still knocking out brilliant paintings.

Wright of Derby: From the Shadows, National Gallery, London, until 10 May 2026. 18th-century master of dramatic candlelit scientific experiments, with a dose of some darker stuff underneath — death, doubt, melancholy, and the sublime. A bijou one-room exhibit, but worth the 12 quid.

Paula Rego: Drawing from Life, Cristea Roberts Gallery, London, until 17 Jan 2026. Featuring over forty drawings from 2005–7, some shown for the first time, and a partial recreation of her studio filled with the dolls and creatures that inspired them. Includes a commissioned set of drawings for wine bottle labels that were too shocking to use.

That’s all for today, GC readers.

Let me know your thoughts! And please help me spread the word about this newsletter by clicking like or restack. Or better still, share it with someone you think will enjoy it.

Thanks for reading!

Love your points about Alma Allen. Maybe the usual tastemakers and cultural influencers are just mad they didn't get their usual way. And I say this as someone who can't stand the Trump administration but also can't stand the myopia and self-interest of the insider art scene.

Hi.

Nicely judged argument with regard Alma Allen’s inclusion at the Venice B.They look like work intensive forms as you say. I think I could like them very much if I viewed them for real.