How Old is an 'Emerging' Artist?

Age barriers in the art world, Judy Chicago in Israel, maths+science+art, and more!

Coming up this week in The Gallery Companion:

What does ‘emerging’ mean anyway? A GC reader shared a recent article with me this week on age barriers in the art world, and I wondered what you thought.

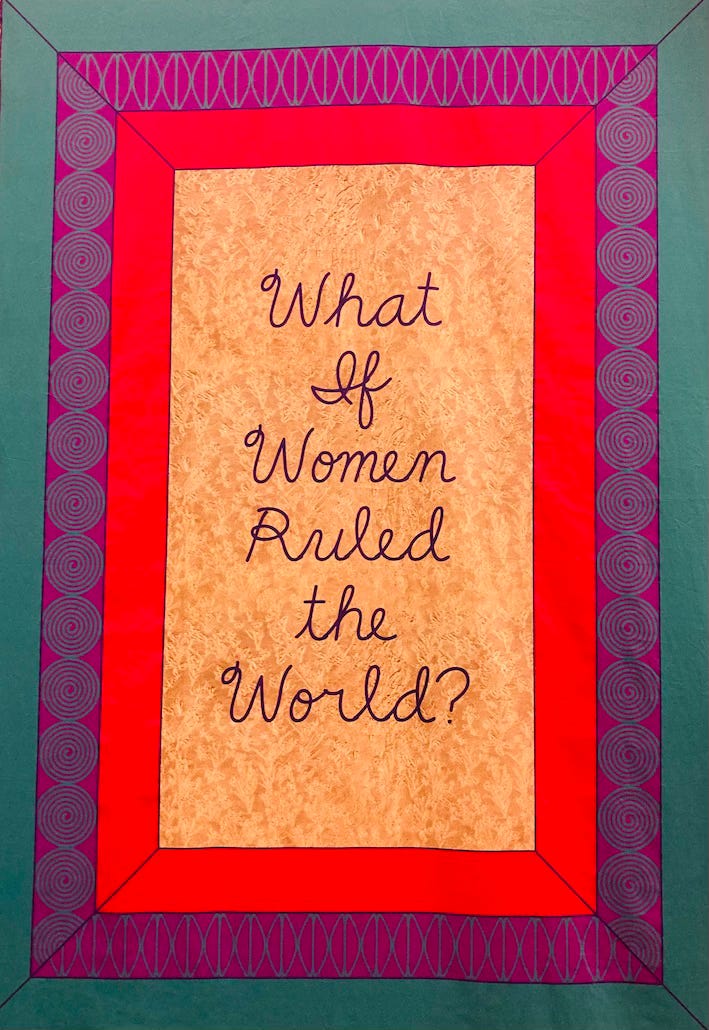

American feminist artist Judy Chicago holds firm in the face of public criticism of her exhibition What If Women Ruled The World? at the Tel Aviv Museum in Israel. And I wondered what you thought about that too.

And I dream about a little trip to Finland to see British artist Keith Tyson’s current exhibition. Once dubbed the ‘mad professor’, Tyson’s into maths, science, physics, astronomy, philosophy, computer technology, and machine systems, and brings all that good stuff into his art.

Plus my list of must-see international exhibitions.

How old is an ‘emerging’ artist?

Last week an article appeared in the online art magazine Hyperallergic about what it really means to be an ‘emerging’ artist. The author shared a story about applying for a fellowship, which supports early-career artists from underrepresented communities in New York. He applied and… Bam! Rejected. Not because his work wasn’t good, not because he wasn’t dedicated, but because he was literally seven days too old. Just a week over the arbitrary age limit, and that was it.

It’s not only the networking and financial opportunities that come with residences and fellowships that older artists are often excluded from. A lot of commercial galleries gravitate towards younger artists to find the next exciting talent.

All of this is a stark reminder of how the art world often equates ‘emerging’ with youth, even though artistic careers are rarely linear. Some artists do follow a straight path from undergraduate to postgraduate to landing gallery representation or residencies and fellowships, sure. But many others start later, take detours, or juggle caregiving — and yet the system still treats them like they’ve missed their chance. As the author argues, there’s an age-constricted conveyor belt that brings legitimacy to an artist:

emerging by 30, mid-career by 40, late-career by 60. If you fall behind, step off, or return later, the system doesn’t know what to do with you.

I can’t tell you how many artists I know who have started their art practice seriously in their 50s and 60s, or later. Some went to art college at the ‘right’ age, before the pragmatics of earning money redirected them to other paying jobs, or the demands of motherhood and family life limited them from being able to pursue their art. Only with retirement, financial stability, or children reaching adulthood have many artists been able to seriously engage in developing their practice and career.

I’m not talking here about those artists who have consistently made art for years, who throughout that time faced exclusion and rejection from the art world, and then found success in later life. There are many examples of these artists, such as Phyllida Barlow, Howardena Pindell and Faith Ringgold.

I’m talking here about artists who have started or returned to art practice in later life and who have managed to successfully navigate the art world for those highly sought-after things: exhibitions, fellowships, project funding, gallery representation, income from sales, reputation. The later-life thriving artists seem to me to be much rarer.

One example is British artist Rose Hilton (1931-2019), who trained at the Royal College of Art in her youth, and whose art career was largely put on hold during her marriage to the painter Roger Hilton. She returned to painting seriously aged 43, after her husband died, and eventually had a retrospective at Tate St Ives in 2008. In this video she talks about her experience as an artist:

But I’m struggling to think of many others. Can you? Hilton seems to me to be one of the exceptions that proves the rule.

I would love to know what you think about this subject. Are you an artist who has begun or returned to art practice later in life? Have you experienced age-related barriers in accessing residencies, fellowships, or gallery representation? Or has your experience been different? Have you ever identified yourself with the term ‘emerging’ artist? Please let me know in the comments!

Judy Chicago at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art: yes or no?

A group of 50 artists and cultural figures has urged American artist Judy Chicago and Pussy Riot’s Nadya Tolokonnikova to cancel the exhibition which opened yesterday at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, accusing them of “artwashing.” In a public letter, they argued that staging a feminist project in Israel is hypocritical given the country’s role in the Gaza conflict, where UN Women reports over 28,000 women and girls have been killed since October 2023. They argue that,

To speak about feminism within an institution of a state that perpetrates such atrocities while ignoring them is hypocrisy.

But the other side to this argument is that cancelling the show risks silencing precisely the kind of voices that insist on questioning power structures.

Freedom of expression means allowing art to exist even in moments of political tension, especially when it is uncomfortable. Judy Chicago’s practice has always been about confronting inequality — gendered, social, and political — and to withdraw her work from view would deny audiences in Israel the chance to engage with feminist ideas at a time when dialogue is urgently needed.

Museums are not governments; they are cultural spaces where contested ideas can be debated. To demand the closure of an exhibition because of the political context blurs the line between criticism and censorship. Rather, it can be seen as an opportunity to bring feminist discourse into a fraught environment, to make visible any contradictions, and to provoke conversations that might otherwise be suppressed. Protecting artistic freedom — even in, or especially in, difficult contexts — is fundamental if we believe in art’s power to question, disrupt, and imagine alternatives.

Pussy Riot’s Nadya Tolokonnikova, who has become an international symbol of resistance, free expression, and feminist protest, collaborated with Chicago in the making of the artwork What If Women Ruled the World, a physical and digital quilt. She responded to the letter by saying that she ‘is not currently involved in any decisions connected to the work or where it is shown.’ Given that Tolokonnikova has been imprisoned by Putin’s regime for her art performances (I wrote about it here in 2023), I’m not sure what to make of this response.

No matter what you think about the Gaza conflict, should we not reject the idea of restricting art from viewers? Censorship of art shuts down ideas and reduces opportunities for reflection. Let me know your thoughts in the comments.

Dreaming of Finland

If ever there was a reason to take a little trip to Finland, seeing British artist Keith Tyson’s latest exhibition at the Serlachius Museum is one of them. Tyson is in the category of ‘late career’ artists, and his work just keeps getting better in my opinion.

If you’re not familiar with his art, here’s a quick what-you-need-to-know: he has been into computers, coding, and maths since childhood; early in his career he was dubbed the ‘mad professor’ and the ‘wacky boffin of art’ for his artworks exploring scientific and mathematical concepts and systems; he won the Turner Prize in 2002; his work is about life, nature and the forces that make things come into being; his practice is diverse, including painting, sculpture, drawing and installation; although he doesn’t really have a recognisable style, there’s a spiritual theme that runs through all the works.

Tyson talks about his ‘strategy’ for making art which uses computers, machines and chance to produce art that pushes and pulls between order and chaos. He once said,

I’m fascinated by science’s dogmatic determinism, the belief that any action, however complex — a Mozart concerto, a terrorist attack — arises from hydrogen atoms bashing together after the Big Bang.

But rather than accept that everything is already mapped out, Tyson uses his art to test those boundaries, building unpredictability into his process.

One of the things I love about his work is that you can see the passage of time passing over the years as he incorporates new technologies and scientific ideas. His 1990s Artmachine, drew together knowledge from books, algorithms and software he coded himself to create a ‘database of the world’ (this was before the wide-spread use of the internet and search engines). It churned out random prompts for him to create artworks from, such as a painting composed of 366 painted breadboards. The Artmachine was pretty basic by today’s standards, but reflected the excitement around knowledge and the potential of computers at that time.

Some of his more recent works use AI in their creation. I think Tyson’s incorporation of this new technology into his art succeeds in being interesting in a way that eludes other artists. 16m³ of Ocean (Atlantic), for example, is a bronze sculpture that captures a frozen moment of the ocean, translating its ever-moving energy into a static cube. Tyson used a photograph from an Atlantic crossing along with AI and modelling software to recreate the surface of the sea and the hidden motion beneath the waves. In this artwork he was confronting the age-old artistic challenge of depicting life’s constant dynamism in a single, still form.

It’s a lovely object, and the explanation of it is much more engaging when he talks about it himself in the 12-minute video below. He also discusses some of the threads that run right the way through his oeuvre from his earliest pieces to his most recent AI artworks. And he almost bubbles over when he explains the scientific and systems thinking behind some of the works in the exhibition. I have to admit I’m not a science boff but I love listening to his explanations of the process of making each artwork:

Let me know what think about Tyson’s art. If you’re an artist and you have themes or processes in your work that relate to his, reply to this email — I’ll share it on Substack Chat for all Gallery Companion subscribers to see.

Three exhibitions I’d like to see

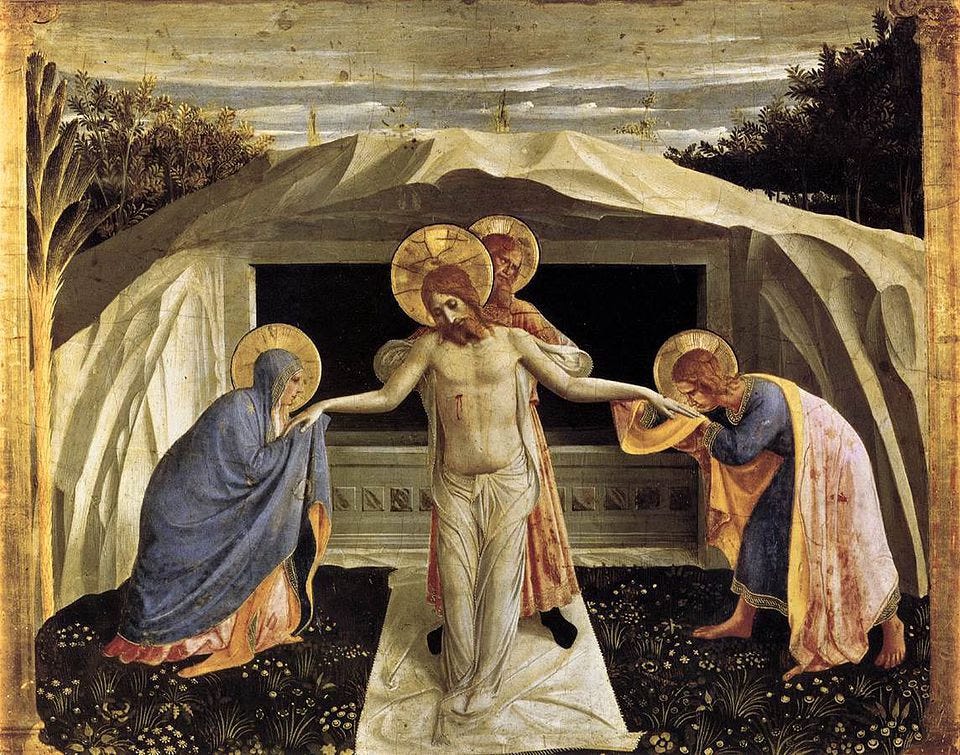

Fra Angelico, Palazzo Strozzi and Museo di San Marco, Florence, 26 Sept-25 Jan 2026. OK, this is exciting. Fra Angelico, who was one of the first artists to play with linear perspective and bring light to life in fresco and panel painting, is getting a huge double-venue show of over 140 works. It’s the most complete look at his career yet, and a chance to see just how modern and dynamic this early Renaissance master really was. Definitely a reason for a little trip to Firenze…

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy of Arts, London until 18 Jan 2026. Marshall makes large-scale paintings of black Americans, drawing on art history, civil rights, comics, science fiction, and personal memory. It has been described as ‘the show of the season’, so get yourself a ticket.

Ai Weiwei: Three Perfectly Proportioned Spheres and Camouflage Uniforms Painted White, Pavilion 13, Expo Center of Ukraine, Kyiv, until 30 Nov. I think this is one just for my Ukrainian readers. In this single work exhibition, Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, has responded to the war with a monumental artwork of three spheres wrapped in camouflage fabric patterned with animals, creating a symbolic structure that reflects on war, nature, and human connection.

That’s all for today, GC readers.

I’d love to know what you think in the comments about any of the things I’ve talked about this week. Or give me a like, if you like it. Or restack my post on Substack. Or help me spread the word about The Gallery Companion: if you know someone who would be into this newsletter please share it with them. Thanks for reading!

Conversely!

I recently received an email from the Pilgrm Hotel in London advertising their Autumn Exhibition. "A celebration of New & Emerging Artists".

Two of the artists in the show have been dead for at least 10 years!

https://thepilgrm.com/article/the-autumn-exhibition-at-the-pilgrm

I came back to art later, after pragmatism and chronic illness took me down a few other paths. And then, suddenly, art was all that mattered. And yes, it’s bloody hard. The art world seems to be geared almost entirely towards younger artists, with a high percentage of residencies and prizes having a cut-off at 25-30. I was also told at an open where I was exhibiting recently that mentorships were really there for younger artists! How depressing, *especially* as a woman…