The Art of Stealing Images

Richard Prince and the complexities of appropriation

In the early 1980s, whilst working in the cuttings department at Time-Life Inc., the artist Richard Prince began developing a series of photographs which came to be known as Untitled (Cowboys). It was during this time, as he rifled through the pages of American weekly magazines, that Prince started to get hooked into the visuals of the Marlboro cigarette ads. These adverts depicted scenes of cowboys on horseback wearing boots, leather chaps and Stetson hats, wielding lassos as they rode through the Western wilderness. They represented an idealised image of macho American masculinity, one which values adventure, freedom and self-reliance. It was one of the great 20th century advertising campaign successes, and Prince was fascinated by the illusion of these alluring images.

After cutting out the editorial columns, Prince was left with a pile of adverts which he took home from work. He stuck them on his wall, carefully cropped the images in his camera’s viewfinder so that none of the advertising text was visible, and rephotographed them. Prince then exhibited the new photos as his own work. His original contribution, he said, was to select the images, crop them, intensify the colour, change their size, and show them in a different context.

With its powerful message about the fantasies we are sold and the truths that are concealed by media imagery, the Untitled (Cowboys) series eventually came to be seen as an important body of work in the history of contemporary art. In 2016 Time magazine added one of the artworks from this series to their list of 100 most influential images of all time.

This brazen borrowing of images without asking permission or giving credit to their original creators has been the pattern of Richard Prince’s artistic output. And it has got him into legal hot water, particularly with professional photographers whose livelihoods depend on being compensated for their work. In response Prince has always claimed ‘fair use’, a legal doctrine in the United States that allows artists to use copyrighted material without first having to seek permission from the copyright holder.

A key consideration of ‘fair use’ is whether the new artwork is ‘transformative’. In other words, the artist must demonstrate that the original has been sufficiently changed with the addition of something new. Essentially what the law does is to allow a degree of flexibility so that creativity isn’t stifled before the artist even leaves their studio.

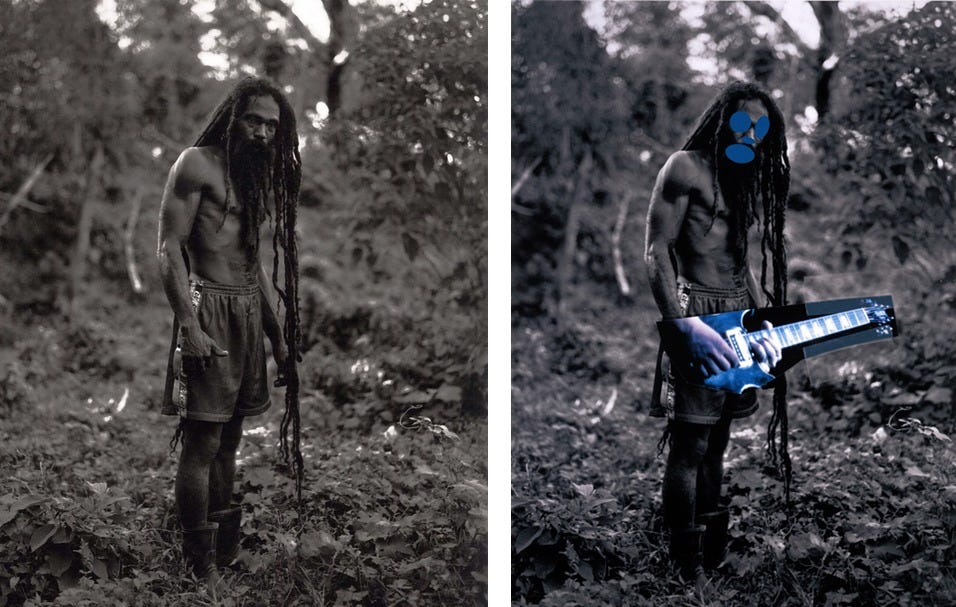

What exactly defines ‘transformative’ is hazy, and judges have historically struggled to navigate it coherently. One test that judges use in fair use cases is whether the artwork is ‘recognisably derived’ from the original, although even this is subjective and has led to contradictory rulings. When the photographer Patrick Cariou filed suit for copyright infringement in 2008 after Prince used 35 photographs of Rastafarians from a series he had shot in Jamaica, a US District Court judge ruled against Prince. Despite cropping, blurring and adding elements to the original photos, Prince did not alter them enough. But that decision was reversed on appeal when another judge decided that most of the images had been sufficiently altered. Five less transformative artworks were sent back to the lower court for review, and the case eventually settled out of court in 2014.

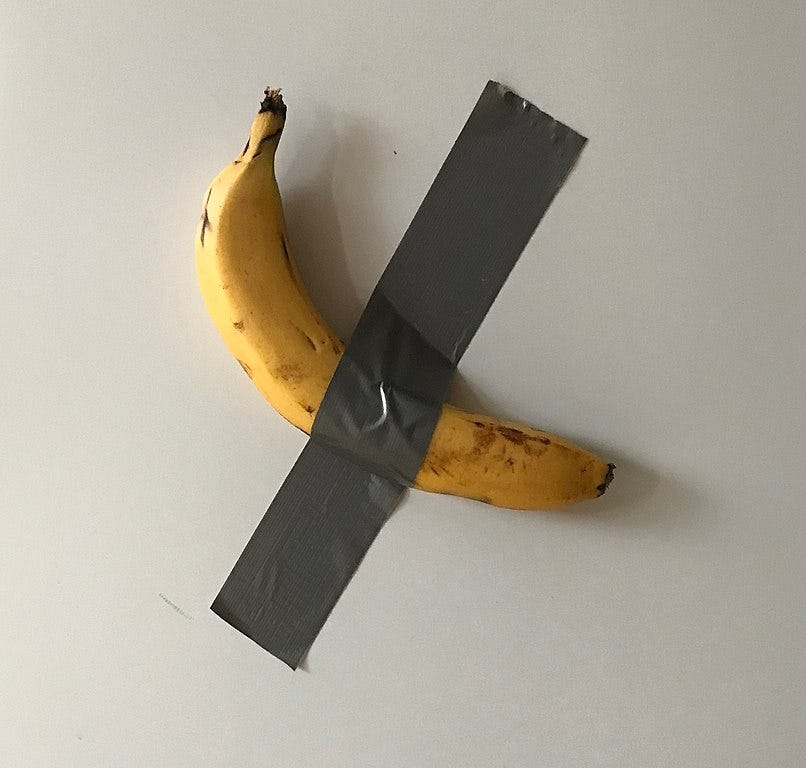

The conceptual artist Maurizio Cattelan is amongst other leading artists who have also fallen foul of plagiarism laws. Cattelan is in a legal pickle with claims of copyright infringement over his most famous artwork Comedian from 2019. The artwork consists of a fresh banana duct-taped to a wall. He is currently battling through the courts in the US against the artist Joe Morford, who claims that Cattelan ‘plagiarised and copied’ his artwork Banana & Orange (2000). Morford’s work consists of two pieces: an orange attached to the wall with tape and a separate work showing a banana affixed to the wall.

The price tag for Comedian was $120,000 for an ephemeral artwork that was doomed to rot away to nothing. In this piece Cattelan was questioning what we value. Even if he did see Morford’s work before he came up with this genius concept, there are visual differences between them as well as differences in their meanings.

The history of art is littered with plagiarism. One idea gets moved on to the next idea, which then gets picked up by someone else. All art is a conversation between artists over time. They borrow, reinterpret, nudge forward, look back. Our visual culture is now more than ever a pick-n-mix, cut-and-paste mashup of billions of images. Recently the British artist Gavin Turk cast a bronze banana in response to Cattelan’s controversial piece. Moving it on, continuing the work, shifting the meaning. Here he is talking about it in a video:

What I love about Turk’s comments in this video is how clearly it demonstrates the creative dialogue that happens between artists. He celebrates the messy layers of complexity and embraces new meanings from small changes.

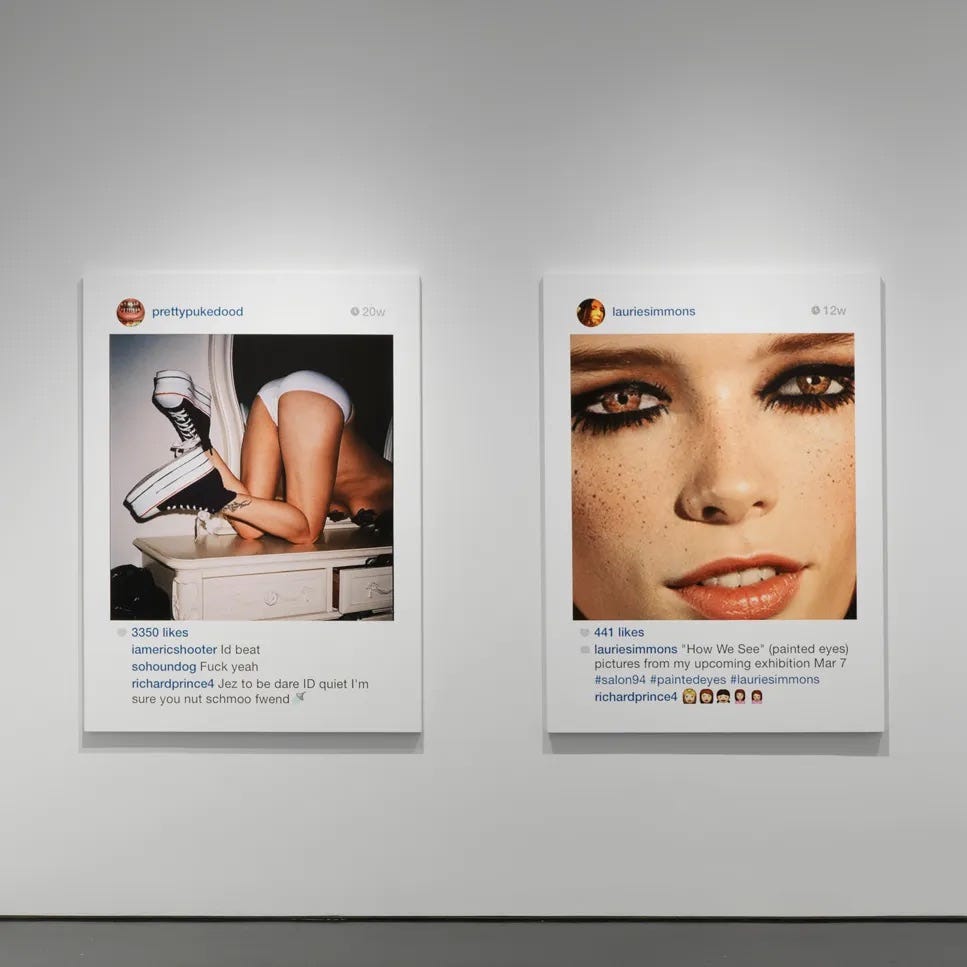

Richard Prince is now back in court again with another two copyright infringement claims for a series of artworks that he made back in 2015 called New Portraits. These works are basically Instagram screenshots enlarged and printed up on canvas. Prince’s creative process involved taking screenshots on his phone from Instagram feeds he was scrolling through. He then cropped them to include the recognisable framework of the Instagram app and some comments underneath the image from followers.

One of the images he screen-shotted was a portrait of Kim Gordon from the music band Sonic Youth, which she had posted on her feed. The professional photographer Eric McNatt had originally taken the portrait for a magazine commission back in 2014, and filed suit against Prince for copyright violation.

In discussing the artistic process behind the creation of the New Portraits series, Prince talked about the way in which he carefully selected the images, the rabbit holes he had been down to find them, how he selected comments and thought about the cropping of the images. This was his own unique contribution. He described it like this:

People on IG lead me to other people. I spend hours surfing, saving, and deleting. Sometimes I look for photos that are straightforward portraits (or at least look straightforward). Other times I look for photos that would only appear, or better still exist on IG. Photos that look the way they do because they’re on the gram. Selfies? Not really. Self-portraits. I’m not interested in abbreviation. I look for portraits that are upside down, sideways, at arm’s length, taken within the space that a body can hold a camera phone.

Once again Prince has used ‘fair use’ in his defence of the Instagram series, claiming that he transformed the images by framing them and using text alongside them, which shifted their meaning sufficiently even if he didn’t change the main photographs in any way. Last week a District Court judge in Manhattan complicated the arguments further, stating that anything additional around the original image is irrelevant, and that the image itself has to be sufficiently altered in order not to violate copyright. Essentially what this does is to remove any consideration of the artistic value that comes from changing the meaning of the image when another artist puts it in a different context. This seems bonkers to me.

Richard Prince is a conceptual artist. His work is all about ideas. One of the reasons many people consider Prince to be a hugely significant artist is because his work consistently makes you think and reflect. It draws attention to the pervasive and often insidious role of the media in our world, the fictions that we consume through imagery, the constructed way we present ourselves and the world around us, the way that power circulates, the myths that perpetuate through the media.

The New Portraits series is interesting precisely because it reflects back to us the experiences most of us are having and the imagery we are consuming on a daily basis. He re-presents us to ourselves. He’s done an Andy Warhol job on Instagram. These artworks also speak to some of the fast-moving big issues in our culture brought about by the massive, open database that is the internet. Questions about truth, privacy, crossing the line, authenticity, authorship, tradition. He makes us think about how we can ever really expect to control imagery when it goes out into the digital space. With the advent of AI imagery, that’s even more pertinent.

By blowing his Instagram images up big and putting them on a canvas in a different context Prince is slowing all of this down for our contemplation, asking us to think about meanings beyond the surface. OK he could have altered the Kim Gordon photo a bit. But wouldn’t that just be a box-ticking exercise to avoid being sued? There’s no question in my mind that his work shifts the meanings of the original imagery that he carefully selects, even if he doesn’t change the image much, or at all. But shifting meaning alone will now potentially be out of bounds for artists if the current court case goes against Prince.

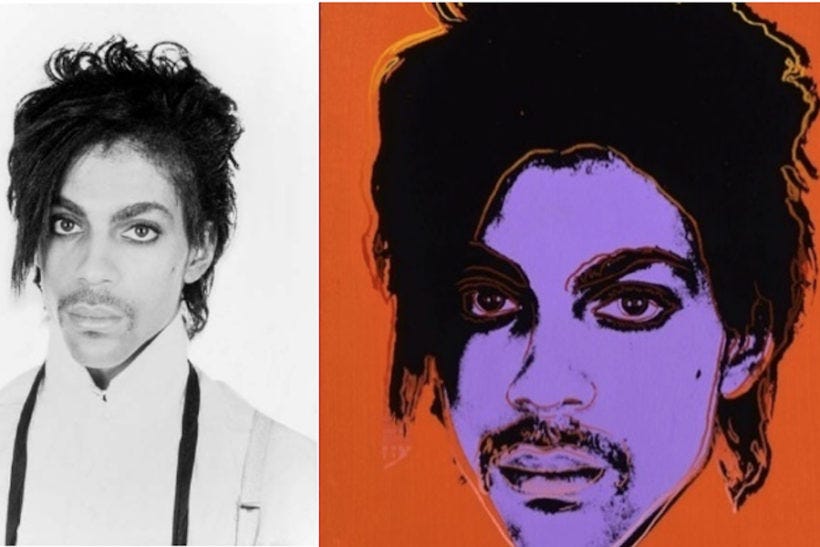

Meanwhile a US Supreme Court judgement last week ruled on a copyright infringement case between the photographer Lynn Goldsmith and the Andy Warhol Foundation over Warhol’s images of the musician Prince. Warhol’s artwork cropped a black and white portrait photograph of Prince that Goldsmith had taken in 1981, to which he applied his recognisable half-tones. The legal case centred around whether the Warhol Foundation should compensate Goldsmith for licensing this Warhol image to Vanity Fair magazine back in 2016 for a commemorative issue. Justice Sotomayer argued that both parties were engaged in the commercial enterprise of licensing images to magazines, and therefore it would be dangerous to authorise copying in this way. Disregarding the idea that Warhol’s later work exists on its own terms, she wrote:

As long as the user somehow portrays the subject of the photograph differently, he could make modest alterations to the original, sell it to an outlet to accompany a story about the subject, and claim transformative use.

Not all of the Supreme Court judges agreed. Justice Kagan suggested the majority needed to go back to school to learn about art history. She wrote that this decision

will stifle creativity of every sort… will impede new art and music and literature… will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.

The different sides of this argument are brought together neatly in this video about Richard Prince’s 1989 Untitled (Cowboy) artwork, in which he talks about his motivations and processes in making art. His ideas contrast sharply with the views of the photographers whose work he has appropriated:

I’m all for artists being paid for their creative work, but I do wonder whether the Supreme Court’s ruling is more likely to hurt artists rather than help them? Should our laws instead work to enable artists to express their ideas freely without having to look over their shoulders all the time? As the media attorney Paul Szynol recently argued in The Atlantic, ‘without strong fair-use protections, a culture can’t thrive’. I know this is a subject that divides opinion, and as always I’d love to hear your thoughts on it.

I recently explored a similar topic “Everything is a Remix” which you might enjoy: https://kenshostudio.substack.com/p/everything-is-a-remix

I'm going to toss this in the mix. I think it's a fresh perspective. Nina Paley on copyright. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XO9FKQAxWZc