Public Art and the Slow Creep of Gentrification

Lauren Halsey and other artists on preserving the memory of community

Recently I’ve really been counting my blessings. I live with my family in a three-bed terraced house in Bristol, a large city just over 100 miles west of London, close to the border with Wales. We moved here in 2016 after being caught in London’s housing trap of sky-high rents and 6-month leasing agreements. With two young sons, it was increasingly unaffordable and precarious for us to continue living there.

So we made the decision to leave our community, our friends, and the streets we knew to start from scratch somewhere else. For less than the price of a one-bed flat in London, we were able to buy a house in Bristol which was big enough for both our boys to have a bedroom of their own.

Our local neighbourhood is a familiar story of gentrification. When we first moved here the ward was one of the most deprived areas in south west England. But things are slowly changing, and the population is becoming ever more white and middle class. More fancy restaurants, coffee shops and organic delis are moving in, whilst lower income residents, mostly of Middle Eastern and South Asian heritage, are moving out.

In just seven years the value of houses in our ‘hood has increased well beyond what we were once able to afford. Our neighbours used to be familiar faces. But as local landlords have increased rents, no one seems to stay long in the overpriced house shares around us. Every so often another white couple from London buys a property down the street.

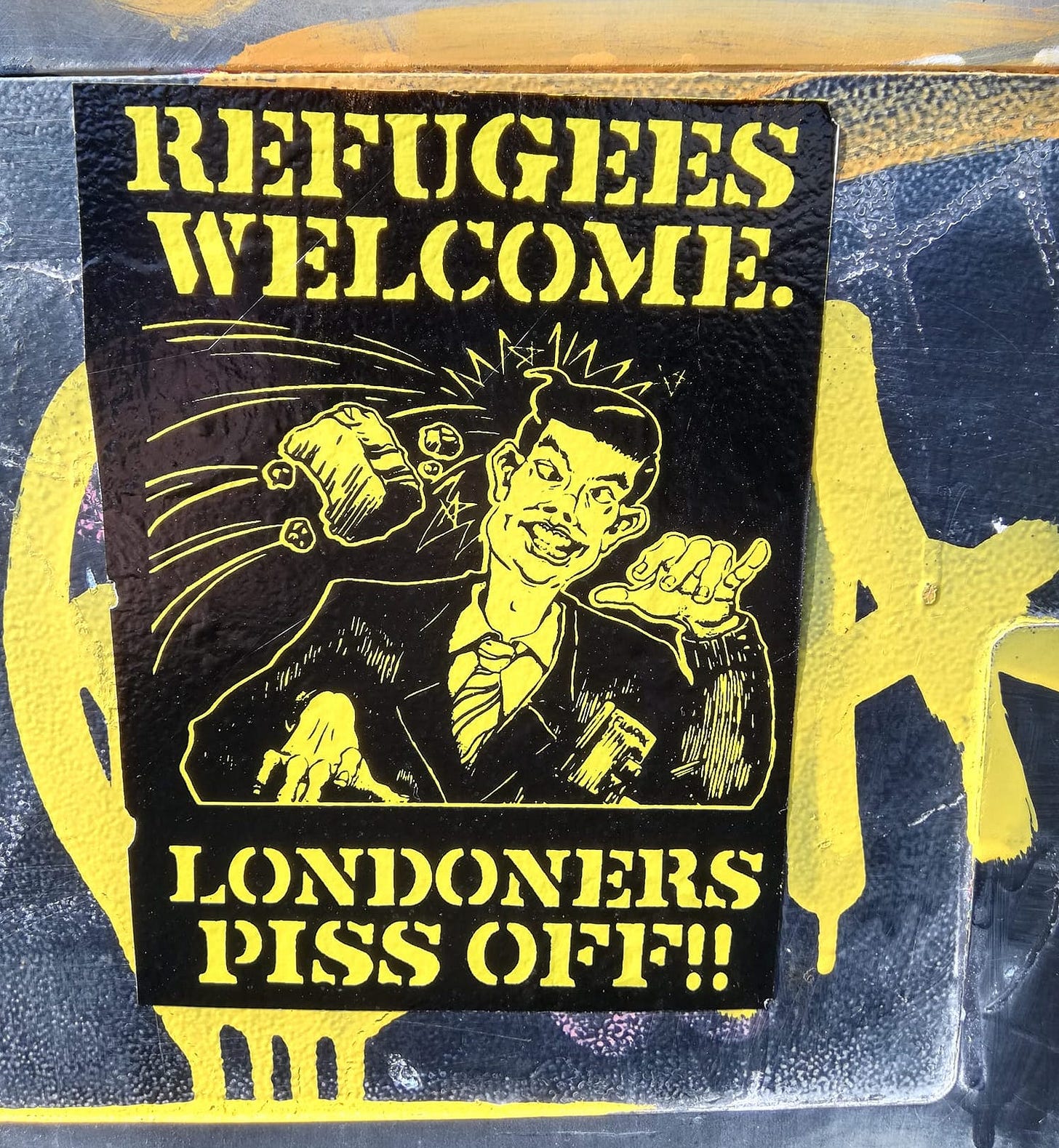

Even as I’m grateful for the security we now have, that we managed to find a permanent home just in the nick of time, I’m aware that we are part of the reason why locals who have been here for years can’t afford to be here anymore. In classic Bristolian sardonic style, stickers and graffiti protest the problem: ‘Refugees Welcome. Londoners Piss Off’.

Stories about the UK’s housing shortages, the sky-rocketing cost of mortgages and rental properties are constantly in the news at the moment. Unless you’re earning mega-bucks it can be a real struggle to find somewhere affordable to live, and for many people it means moving away from a community that has provided friendship, familiarity, support and structure. All of these things matter to our sense of belonging, connection and identity, particularly for marginalised groups who feel strength in numbers in visible communities.

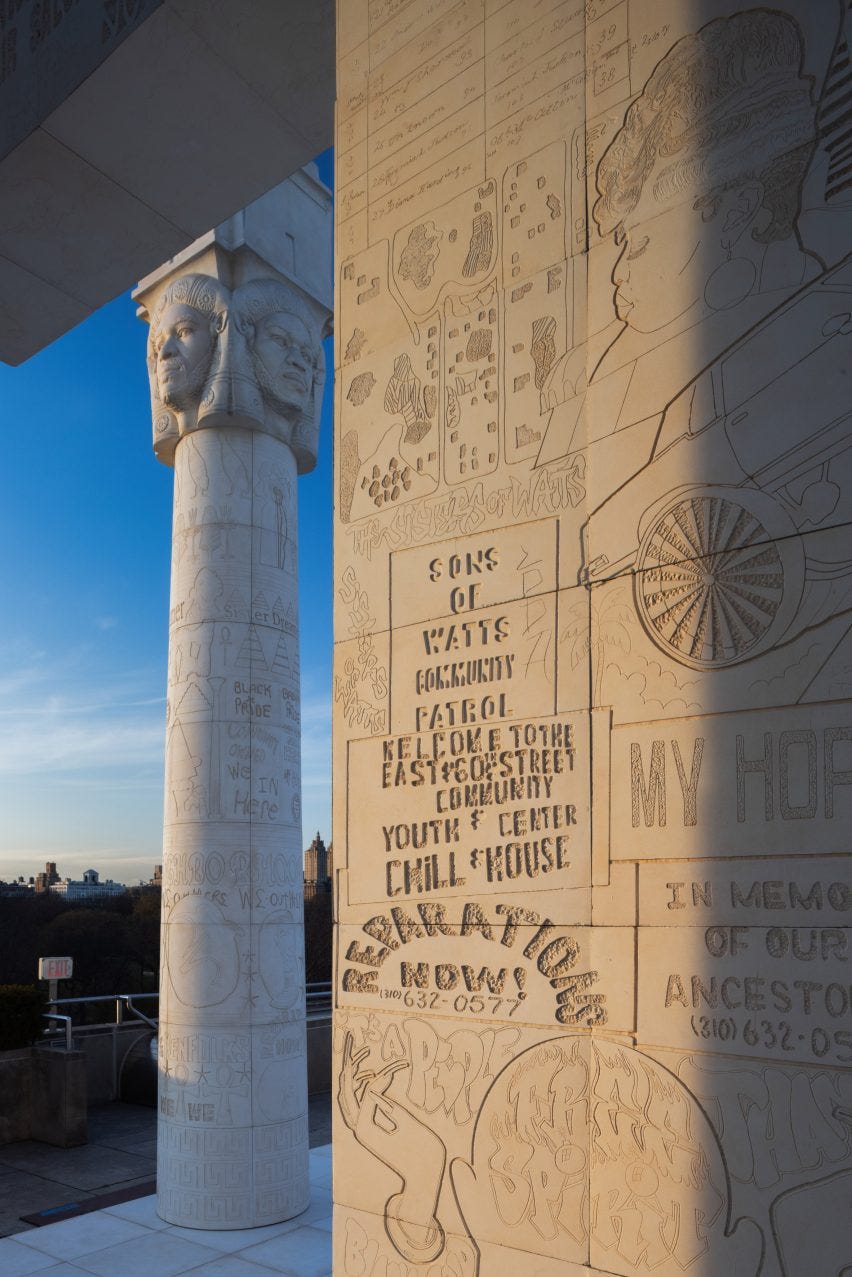

I was thinking about this as I was watching the Los Angeles-based artist Lauren Halsey talk about her recent work, a sculptural installation on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum in New York this summer. It’s a sort of Egyptian-style temple, with sphinxes guarding the entrance and hieroglyphs covering the stone facades. But as you look closer, you start to see signs of contemporary urban culture in the faces of the mythic statues and the imagery and words inscribed on the walls.

The sculpture is an homage to the local community of South Central L.A. where Halsey grew up and still lives. It’s inspired by the ancient Egyptian collection at the Met, but the details are contemporary and personal to the artist. The faces of the sphinxes and those at the top of the columns are portraits of members of her family and friends.

The inscriptions on the walls are local and personal too. Carved into the stone are familiar street and shop signs, graffiti tags, fliers, images and phrases documenting and celebrating contemporary Black and brown L.A. culture. Halsey’s art practice is archival in nature: she has been collecting these documents since 2007. In this artwork she remixes and re-contextualises them into freestyle compositions.

After its temporary installation in New York the sculpture will transfer to L.A. where Halsey intends to find a permanent location for it on a main boulevard in her local neighbourhood. She dreams of it being a site where Black and brown Los Angelenos can think about the visual richness of the area’s culture and community.

I love so many things about this sculpture. First and foremost it’s a treat to explore with the eyes. It’s for deep looking. And I like the way in which Halsey is using art here to try and shift long-held ideas about race and violence in this area of L.A., highlighting instead through the visual imagery the strength of personal and cultural ties that underpin strong community. The sheer size and weight of the sculpture represents the presence of her community in solid form.

But just like my neighbourhood in Bristol, South Central Los Angeles is in the process of gentrification. Halsey’s community is already under threat and is slowly dispersing. Housing pressures in L.A. have led to recent changes in planning regulations for building new homes, and the COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced economic inequality in Los Angeles. Now million-dollar houses are the norm even in South L.A., pricing out its long-time residents in the rented sector, and tempting existing home-owners to cash-in and ship out.

Perhaps it is inevitable that this community will eventually disperse. There are many examples of tight-knit social groups breaking down and moving on throughout our history, all over the world. Signs of wealthy communities often stay visible in the built environment over time, but the traces of marginalised communities are much less likely to be preserved. Which makes it all the more important that Halsey’s sculpture finds a permanent home in the streets of L.A.

Halsey’s art makes me think about the New York-based artist Abigail Deville, whose work reclaims the histories of marginalised people who have left no visible trace on the urban landscape. She creates site-specific immersive installations using discarded materials to mark their presence in the places they occupied and to acknowledge their role in shaping them today.

In a 2014 art documentary DeVille pushes a cart filled with rubbish around Harlem, an area of New York under constant pressure from development and gentrification. She visits her grandfather’s childhood home, now much altered, before going to the site of an African burial ground at the base of the Willis Avenue Bridge, where free and enslaved families buried their dead. The site dates back to the seventeenth century, and is a neglected no-man’s land when DeVille creates a sculptural installation here using old bits of wood, rusty metal, mannequin heads, and rubbish bags - trash that for her represents the way her ancestors were treated.

For me the interesting thing about this film, aside from Abigail DeVille’s sublime way with words, is the idea of the importance of marking place to make visible what is invisible. To acknowledge the presence of those who have gone before. This abandoned burial ground dates back centuries, but it still has real meaning in the present. And not just for DeVille, whose family has lived in New York for generations, but for everyone. It says a lot about what we have valued - and not valued - enough to preserve.

It speaks of the long history of African Americans in the USA, and the sidelining of this history in favour of historical narratives written by and about white people. This is an ongoing issue in the USA. The history that American children are taught is very much still a matter of contention. In Florida earlier this year the high school curriculum on African-American history was revised after conservative critics complained it amounted to ‘woke indoctrination’. This is a pattern now increasingly seen in other states across America.

A broad knowledge of history, including the history of minority and marginalised groups, enables us to be more critical in our thinking about ourselves and the world. And it can empower those who have felt oppressed. DeVille has talked about the powerful moment she first heard Dr Martin Luther King’s I Have a Dream speech when she was at school as a ten year old kid. It gave her validation and a sense of her place in history.

Public art also has the power to validate in this way. This is what happened in New York recently with the public sculpture Day’s End by the influential artist David Hammons. The huge artwork was erected in 2021 on the west side of the River Hudson, mapping the exact dimensions of the Pier 52 shed which was torn down 40 years ago. The sculpture consists of the architectural outline of the pier shed constructed in steel tubes. It was inspired by a work of the same name by the American artist Gordon Matta-Clark, who carved huge holes in the walls of Pier 52’s dilapidated warehouse with a chainsaw back in 1975.

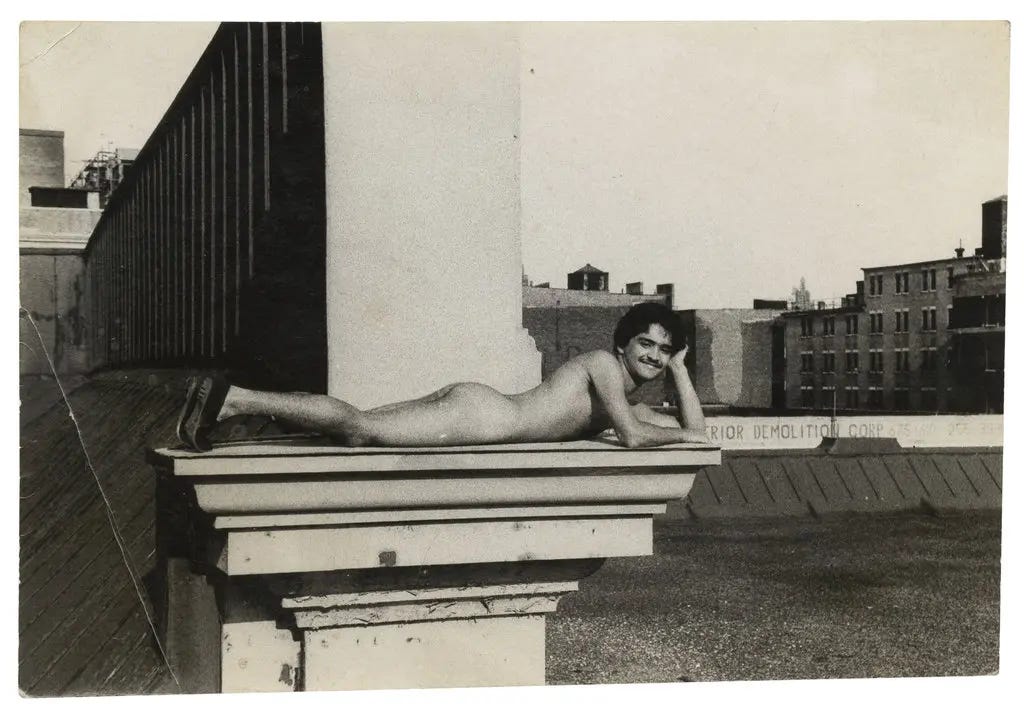

Hammons’ sculpture certainly gives a nod to a great artist who died young. But it also marks a New York site that has a rich queer history. Pier 52 was part of the world’s largest port from the start of the 20th century, and after it was abandoned and fell into ruins became a site of socialising and sex for the gay community in the 1970s, prior to the AIDS epidemic. Thanks to the American photographer Alvin Baltrop we have documentation of this bygone subcultural world. Through his photos we see individuals and their personalities, as well as the aesthetics of the abandoned building.

In a moving video produced by the Whitney Museum, members of the LGBTQ community discussed the meaning and significance to them of Hammons’ public sculpture: it serves to remember them and permanently marks their presence in the urban landscape before development and gentrification swept away the safe haven they had created. It’s a quiet, graceful monument that values their place in the city’s history.

Cities are always changing, nothing stays the same. The slow creep of gentrification seems inevitable in our current economic system, and I don’t know what the solutions are to the problems I’m part of. But I do think it’s important to preserve the memory of marginalised communities visibly and permanently in public space. Lauren Halsey’s Egyptian-inspired sculpture brilliantly speaks of these issues.

As always, I’d love to know your thoughts on any of the ideas I’ve discussed here, what you think of the housing crisis, gentrification, or any of the artists and artworks I’ve talked about.

Another excellent, thought provoking article and introduction to artists making important, valuable work.

I agree with Tyler's comment that gentrification is just the symptom of a deeply flawed political system that enables, encourages (& even ultimately forces) the security of a lucky few to be at the expense of those in the margins who must accept an increasingly precarious rental system. This could be reversed if the government - and therefore the people, chose to vote that way.

Thanks for this essay. The gentrification issue is one I've thought about a lot over the years and I can relate to the tension of having certain privileges that contributing to the process of displacement, even unintentionally, and being aware of that while feeling frustrated about how you're placed within the cycle of gentrification.

There's also a hierarchy to gentrification, which means that those with some means, but not the most means, often lack the full range of options, and thus move into more affordable areas, but as a result of certain status(es), make the area more amenable to more privileged classes. Low-income artists are a famous example of this, as they're drawn to neighbourhoods that have the space and 'character' they like but in moving into such areas, make it "cool," causing middle-income professionals to move in, before the wealthy make their claim. You see this in expensive cities from Vancouver to Melbourne, but also in relatively "affordable" cities as you've noticed with Bristol.

Ultimately, I think a lot of folks get stuck on "I don't know what the solution is." And honestly, I don't have all the answers either, as I'm still learning and pondering. But we're often looking for incremental changes or reforms to the existing system so that the comforts of those who can have a say aren't disrupted too much in the process (not saying this is you or anyone in particular). The housing crisis is a major issue across the world and isn't being fixed by density bonuses and YIMBY-at-all-costs rhetoric.

If we can agree that housing is a basic human right, which most seem to, then it begs the question of why we've allowed it to become so commodified and treated as an asset or investment above all else. This process should be ridiculed as much as the left (and centre to some extent) ridicule encroaching healthcare privatization. The solution to this conundrum is to de-commodify housing as much as possible. Which is, yes, radical, and probably something most with the ability to move the needle on this don't want to do because they tend to have greater access to wealth in our society. But, if we can decouple housing from capitalist frameworks, it can lead to healthier, more sustainable communities that can maintain themselves without the threat of a bike lane causing a rise in rents. Because we should all have bike lanes in our neighbourhoods. In the Anglosphere, we've moved so far beyond this that it seems unrealistic or far-fetched, but it wasn't that long ago that governments were investing much more in public housing, and in some places, they still constitute a significant portion of homes (Austria, Singapore).