It's Activism, But is it Art?

Some thoughts on the feminist art exhibition at London's Tate gallery

Shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, shoppers noticed strange changes to the price of goods in supermarkets across Russia. Chocolate appeared cheap at 14 rubles a bar, jars of coffee 400 rubles. As consumers looked at the price labels more closely they read about the 14 lorries of humanitarian aid that had been blocked from entering Kherson to reach desperate Ukrainian civilians, and they learned about the 400 people that had been sheltering in a school building as it was blown up by the Russian army.

At the start of the Ukrainian invasion the Russian president Vladimir Putin made it illegal for citizens to say anything negative about the war, cracking down hard by arresting and imprisoning people who openly protested against what was going on. Quickly seeking alternative ways to challenge this tyranny of the state, artist activists put together DIY packs of false price tags with anti-war messaging that people could print out and put up in their local shops. In a country where the government controls all media messaging, these were small, disruptive acts of protest to raise awareness of what was really happening. The intention was to get Russian civilians to question government propaganda in quiet, non-violent ways.

On Thursday last week the 33 year old artist and musician Aleksandra Skochilenko was found guilty of ‘knowingly spreading false information about the Russian army’ and was sentenced to seven years in a penal colony. After she had put up five of these labels in a supermarket in St Petersburg last year, she was tracked down and arrested. Skochilenko was using a creative visual form of communication to speak directly to her fellow Russians. This kind of activist art which is dispersed in public space, connecting person with person, integrated into everyday life, side-stepping dominant channels and institutions of power to present alternative perspectives, is vital and real. It can bring hope to people where there is little hope.

As news of this young woman’s long and overly-punitive prison sentence was breaking, I was visiting the Tate gallery in London to see Women in Revolt! an exhibition that has recently opened about the role that art played in the women’s movement in the UK in the 1970s and 1980s. It’s packed to the rafters with activist and protest art, much of which has never been seen before in a major museum like the Tate. The curator Linsey Young has researched and uncovered an extraordinary collection of artworks that document the many voices and experiences of women during this time. This art questions the systems that dominated women’s lives, and still do: legal structures, capitalism, the patriarchy, cultural expectations and attitudes about women.

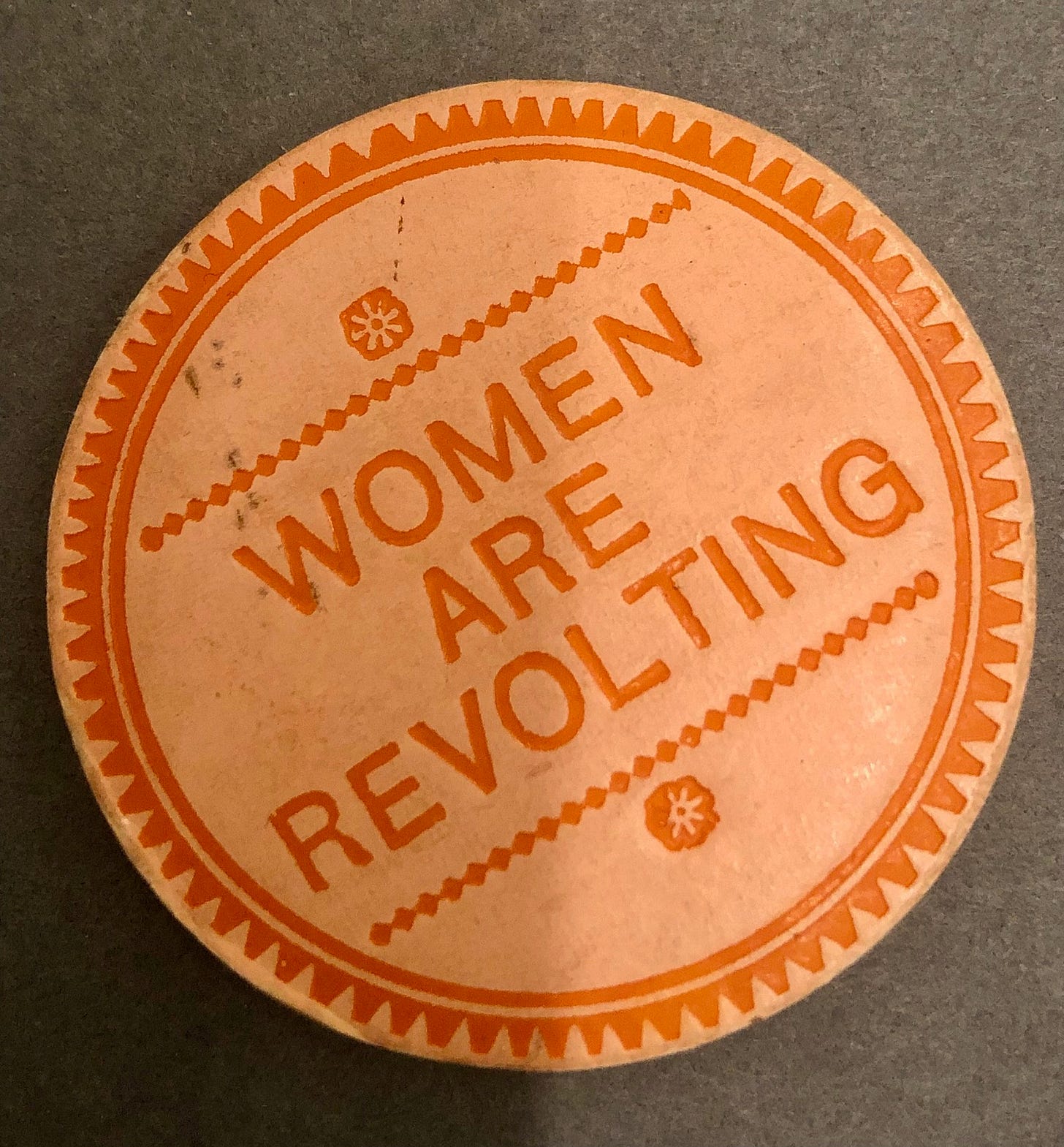

I felt total exhilaration from the minute I stepped through the doors. The first room was buzzing with people, mainly women, and there was the sound of laughter and conversation between friends and strangers discussing, reminiscing and sharing thoughts about what they were looking at. The rooms are almost bursting at the seams with all types of art — paintings, films, posters, photography, zines, badges, installations, videos of performance art, objects made from all sorts of materials, sculptures, drawings. It is a rich tapestry of visuals from this period in history. It feels to me like the curating of the show reflects a sort of explosion of frustrated voices. And I mean that in two ways — the voices of women who were expressing the frustrations of their lives fifty years ago AND the fact it has taken this long for their work to be officially recognised.

I loved learning about the female artists that I had never heard of before; and about how isolated women connected with each other through artist collectives and networks. But it wasn’t just about supporting each other as artists, it was also about raising wider awareness amongst the general public about the things that were stacked against women: misogynistic attitudes, partial access to healthcare and jobs, legal inequalities, the burden of domestic work and childcare, and so on. Sue Crockford’s documentary film A Woman’s Place from 1972 nails this complexity, combining footage from the early marches for equal rights and discussions at the first Women’s Liberation Movement conference in Oxford, with vox pops attitudes gathered from nearby streets.

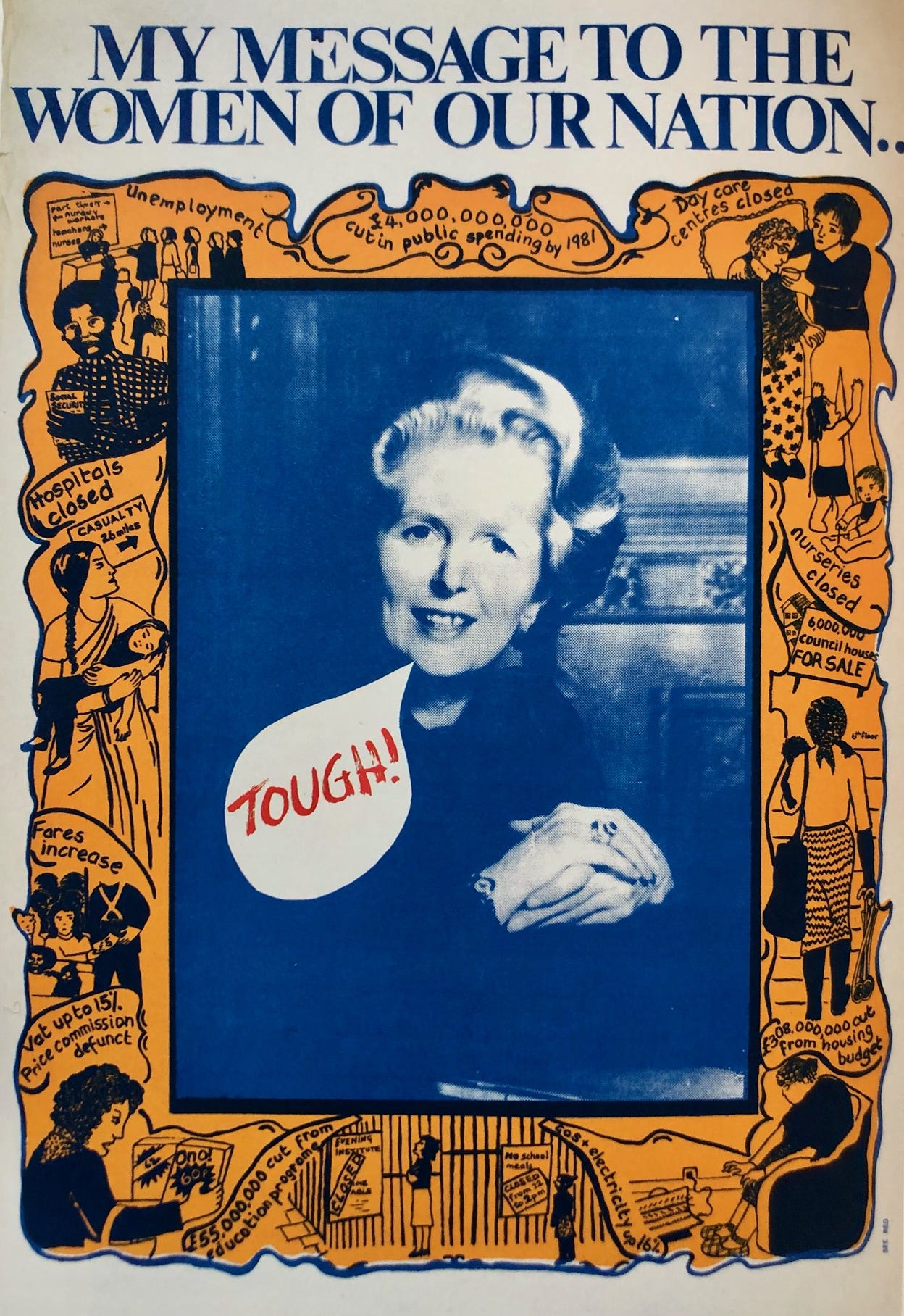

What came across loud and clear were the creative ways that women used whatever they could, whatever materials they had at hand, sometimes with very limited financial means, to express themselves, to connect and to get people to question the status quo. The See Red Women’s Workshop, for example, set up in 1974 to produce posters that explored and countered negative images of women in the media. They funded their work by selling posters at affordable prices and by doing service printing for local community groups. Over the course of sixteen years more than 45 women were part of the collective, producing posters on subjects like childcare, marriage, sexuality and discrimination.

These are striking images that made me laugh but also pack a punch in terms of political messaging. One of the See Red posters from 1979 depicts a portrait of the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher surrounded by drawings detailing the impact of her rightwing policies on many women. The headline reads ‘My Message to the Women of Our Nation…’ A speech bubble from her mouth says ‘Tough!’

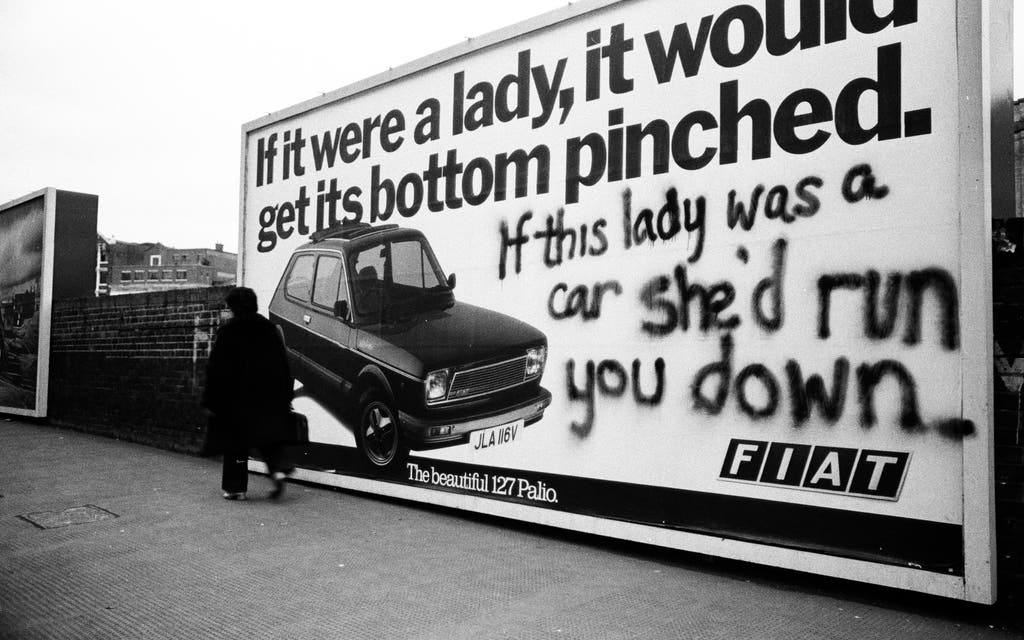

I also loved the work of the photographer Jill Posener, who disrupted sexist advertising on billboards with graffiti in the late 1970s and early 80s. In Fiat Ad from 1979, the slogan on an advertisement depicting an Italian car reads ‘If it were a lady, it would get its bottom pinched’. Underneath it Posener has scrawled in spray paint ‘If this lady was a car she’d run you down’. The black and white photograph that she took is the visual record of her protest, a feminist act that questions the sexual objectification in consumerist messaging in public space. She sold the prints as postcards to raise funds for radical causes.

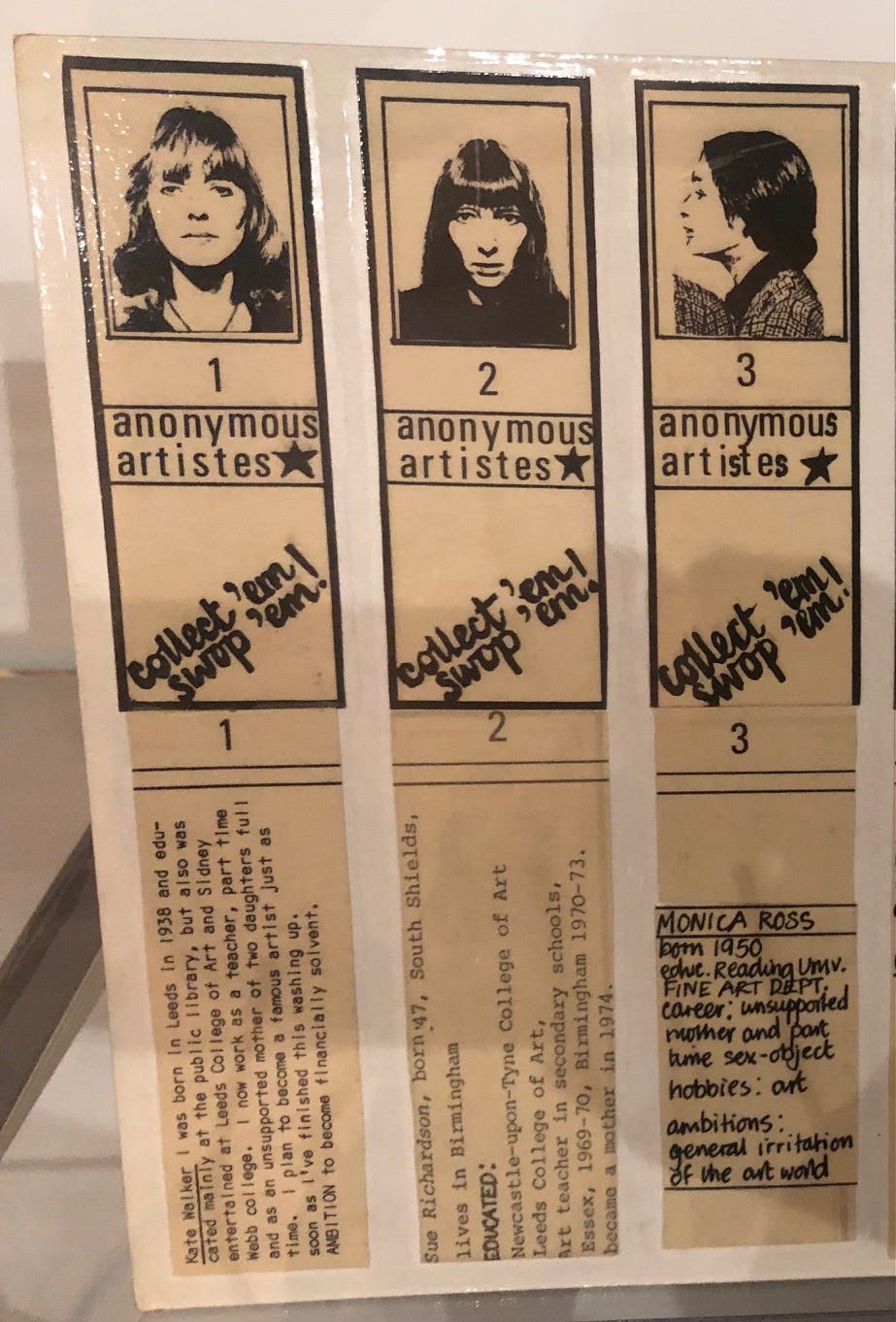

One of my favourite new discoveries was the Postal Art Event which ran for two years from 1975. The artists Sally Gollop and Kate Walker started sending artworks to each other in the post, and it quickly expanded as female artists from all over the UK joined the network. These artworks had to be small enough to post in the mail, and were made from things assembled from their homes. This was all about women connecting with women over their everyday experiences as housewives and mothers. Their boredom, isolation and frustration, and their feelings about the lack of opportunity in a male-dominated art world that excluded them.

I loved one of these postal artworks by Kate Walker titled Anonymous Artistes. Collect ‘em! Swap ‘em made of card and sticky-back plastic. There are thirteen of them that look like bookmarks, and have a profile photo and stats of different female artists written on each of them. Kate’s own card details her outstanding art education credentials and then reads

I now work as a teacher part time, and as an unsupported mother of two daughters full time. I plan to become a famous artist just as soon as I’ve finished this washing up.

The sense of frustration and the tension between being a mother and an artist is palpable in these hand-crafted objects. But just like Skochilenko’s false price labels in the St Petersburg supermarket, these artworks functioned as small acts of protest connecting woman to woman, integrated into everyday life, side-stepping dominant modes of communication to express voices and views that weren’t being heard. These women gave each other hope.

This kind of art that empowers individuals and communities is vital and life-affirming. So I was amazed to read the blistering review from the critic of the Financial Times Jackie Wullschläger on this exhibition. She says:

Tate has mustered hundreds of works so minor, and often puerile or even hate-fuelled, that it’s extraordinary to encounter them in a museum… The misjudgment of parading ephemera as gallery-worthy exhibits is fatal — and a wasted opportunity. The 1970s were an astonishing moment for women’s art, when second-wave feminism — demands for equality, reproductive rights — met the beginnings of conceptualism. It could have been a fascinating subject.

To be fair to her, she does give a nod to a few works by artists she had probably heard of before — Helen Chadwick, Linder, Marlene Smith — lest anyone accuse her of thinking that there have been no great women artists because women are incapable of greatness. But these artworks, in her words,

contrast glaringly with the majority of obscure, humdrum, make-and-mend pieces which have no aesthetic distinction.

I’m just gobsmacked by this dismissive description of the remarkable creative output of these women. Wullschläger seems to question whether some of it is even art at all. I thought we had established long ago that art now comes in many different media and means of distribution, and that it isn’t necessarily about demonstrating the skilled hand of the artist but rather about communicating ideas in visual form. And I certainly thought we had wrapped up the debate on whether art can or should be judged on culturally shifting standards of beauty. Art is not just for decoration. Hers is an outmoded, elitist view of what art is and what it’s for.

Of course it’s fine to think that some artworks are bad, but there’s something about the tone of Wullschläger’s review that suggests this exhibition has a woke agenda that is providing a false platform to raise up artists who are not worthy of our consideration. She describes the exhibition as a ‘politically-driven, incoherent mess’.

It was my friend Hall W. Rockefeller who alerted me to this review, knowing it would absolutely infuriate me as it did her. Hall is an art critic and writer specialising in the work of female artists, and she’s the founder of the Less Than Half Salon, a virtual community that brings together women artists for connection, inspiration and shared resources. Follow her Substack here. She’s a fearless champion of women’s art practice, and constantly works to raise awareness of the fact of systemic sexism in the Art World, which is notorious for gender inequity. Recent studies have shown the extent to which women are underrepresented and undervalued in museums, galleries, and auction houses. Add race into the mix and it’s a double whammy. It’s almost as though Wullschläger is ignorant of all the structural reasons why women have been largely invisible in art history, and doesn’t understand her own role as an art critic in compounding that. As Hall says,

the idea that women and people of colour are included in the canon just because we have to ‘look good’ and do ‘the right thing’ is such a pernicious and harmful idea that we have to be so careful when we even suggest that as a possibility in writing about art.

Wullschläger seems to have missed the point of the exhibition entirely. I think it’s a tour de force in the way it interweaves British social history with what was happening in the visual arts. Of course it doesn’t tell the whole story, no history can. But more knowledge about the visual expression of that fight for equal rights by women complicates and adds nuance to our understanding of our recent past. It enables us to be more critical in our thinking about the present and to understand ourselves better. What is so clearly demonstrated in the uncovering of these artworks and artists’ stories is precisely how patriarchal mechanisms in society operated at the time to keep this postwar generation of female artists on the peripheries — and since then to keep them out of institutions and art historical narratives too.

By suggesting that this activist/protest art is not worthy of being collected by one of our national cultural institutions, Wullschläger raises the question of what we value as a society. As an historical researcher I’m always aware and thinking about what has been preserved and what is left out of archives — and why. Who decides what is worth keeping? Thanks in part to this research project by the Tate, we’ve now made inroads into the permanent preservation of records celebrating the lives and creative achievements of more women. That’s a significant thing in art history, although it’s already too late for some. On the patchiness of the remaining archives, Linsey Young writes in the exhibition catalogue:

I have had sleepless nights about who has been excluded; some artists could just not be found, some have died prematurely, and a number of artworks have been lost forever because many women artists were not able to afford storage for their work, or simply found the effort of maintaining hope that someone would one day pay attention too exhausting.

It’s true that the art in this show is often overtly political in subject matter, and many of the artists featured were socialist and anti-capitalist in their views. But does that mean that our national institutions should steer clear of researching these artists and buying their work? Things have changed significantly over the past fifty years — laws have changed, employment opportunities for women have changed, social attitudes have somewhat changed. But what is really interesting is how relevant much of what these artworks communicated then is still today, how live and ongoing the issues are: continuing male violence towards women, endemic misogyny, women’s greater burden in domestic work and childcare, the sexual objectification of our bodies, the wage gap, the lack of women-only spaces, the double discrimination of being black and female. The exhibition shows there is still a long way to go in the fight for real equality between the sexes. And the queues of people waiting to see it speak volumes.

As always I’d love to know your thoughts on any of these artists and ideas so please click on the comment button below to leave a message.

If you love what you’re reading from me, become a paid subscriber and get special access to everything I send out, and the entire back catalogue of my writing. It’s a fiver a month.

Lovely piece (and great job with your voiceover, too). This reminds me of an old debate from graduate school, about whether cultural artifacts such as advertisements might be "texts." I enjoyed experimenting with that cultural studies approach as a teacher, and while I think it has some limits, you've outlined fantastic examples here. I'm reminded of an exhibit I once saw in Philadelphia with many artifacts from the 1910s, leading up to the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote in 1920 (so recently). The one that struck me the most was a Christmas stocking that said, simply, "Bring a vote for Mother."

Here's another gem: https://tinyurl.com/4yknu8k3

This point of invisibility can’t be stated enough. You really pack punch into your criticism of this FT Review, and rightly. What really strikes me is the way you felt immersed in the experience of this exhibition. It’s as if the reviewer went alone or after hours -- how could one ignore the buzz you describe? Your article brings up so many important points and questions, especially about the necessity of the continuation of this dialogue.

Trying to squeeze in a visit myself!