Banned Body Bits

Censored art, religious graffiti, Monet and more!

Coming up this week in The Gallery Companion:

I’ve been thinking about the mountain of criticism that the new exhibition opening today at Canterbury Cathedral has already received. What’s it all about and is the anger justified?

An exhibition in New York is showing art that has been censored in the US in recent years. Which got me thinking (again) about art we’re not allowed to look at, specifically work that represents the more intimate parts of the female body.

Plus my list of must-see exhibitions, and a new section introducing you to artists from The Gallery Companion’s readership.

Graffiti and grace

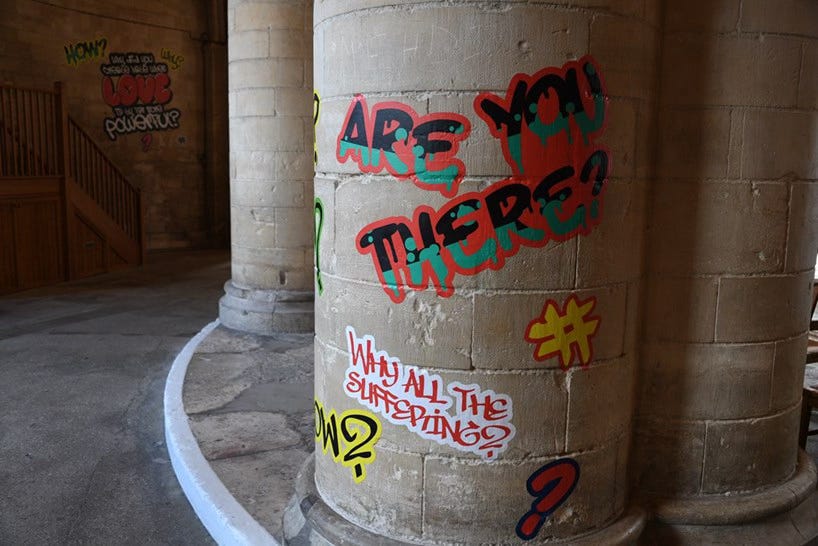

This week there have been more raised eyebrows about the ‘progressive’ tendencies of the Anglican Church. After recently appointing a woman who’s fine with same-sex marriage as the Archbishop of Canterbury (the spiritual leader of the Church of England), a new exhibition opening today at Canterbury Cathedral is drawing yet more heated / angry comments. HEAR US features graffiti-style works created in community workshops in response to the question, ‘What would you ask God?’

The installation, which incorporates messages from marginalized groups, including the Black and Brown diaspora, neurodivergent, and LGBTQIA+ communities, aims to foster inclusivity and amplify diverse voices within the cathedral space. The dean of the cathedral emphasised that the exhibition builds ‘bridges between cultures, styles, and genres’ and highlights contributions from younger participants.

Critics have denounced the graffiti-like aesthetics and questioned the appropriateness of altering a historic religious site. Worshippers have called it ‘sacrilegious’, ‘awful’ and ‘more suited to an underground car park’. Online, Elon Musk called it ‘shameful’, and the US Vice President JD Vance wrote on X:

It is weird to me that these people don’t see the irony of honoring ‘marginalized communities’ by making a beautiful historical building really ugly.

These criticisms of the project are way too harsh. It’s not that I’m wild about the graffiti style — in fact I think it’s very basic and school-project level in its sophistication.

But what I do like about it is that it challenges traditional notions of beauty in a space which is loaded with ideas about authority, taste and history. There’s no attempt to fit in to the look of the building — the soaring Gothic features, the intricate decoration, the stained glass, the gold of the chalices, candlesticks, altarpieces. The exhibition disrupts the cathedral’s polished harmony, transforming its architecture from a grand historical monument to a down-to-earth space for dialogue. Against the sand-coloured stone walls and pillars, the colourful artworks positively demand to be engaged with — you just can’t miss them.

The exhibition also raises questions about site-specificity, context, and audience expectations: how does the meaning of art change when installed in a sacred, historical space rather than a white-walled gallery? What might seem reflective or critical in a gallery can take on greater emotional intensity — or provoke discomfort — in a consecrated space.

These artworks resist the critical distance that art history usually gives us. It’s hard to look at them without becoming entangled in the living language of Christian belief, in contrast to the cool, historical gaze through which we now encounter, say, an early Renaissance painted altarpiece.

I can’t quite work out how I feel about this exhibition. It interests me because it (possibly unintentionally) sticks two fingers up at authority and taste: I love how it riles people. But the Christian context and messaging also makes me feel slightly uncomfortable, like I’m intruding on other people’s faith.

I wondered what you thought about it? Let me know in the poll below and in the comments.

No pubes in art, please.

Over in New York, an exhibition titled Don’t Look Now, is featuring artists and artworks that have been censored in the US in recent years. On first reading about it, I naturally thought: ‘Yes please! Tell me more! Show me the images!’ Because of course when art is censored it attracts more curiosity than it might otherwise.

What struck me as I perused the list of artists and looked up some of the artworks is how visually gentle so much of it is. There’s nothing that’s actually intolerable to look at (for me at least) — the artworks are more poetic and beautiful than outrageous.

Don’t Look Now demonstrates that censorship happens more frequently today than you might think. I was aware of several attempts in the past fifty years to censor art made by women in particular. Margaret Harrison’s 1971 exhibition of drawings critiquing the objectification of women in popular culture, which was shut down by the police after just one day, is one famous example. Still, it did surprise me how much imagery representing the female body by relatively unknown artists has been censored even in the past ten years.

The perceived threat from female sexuality and the idea that women might want to control their own bodies has driven this censorship. Take Marilyn Minter’s Plush series from 2014, for example, which depicts female pubic hair, and which has been regularly censored from exhibitions and social media.

Minter is an American artist known for her work exploring women’s bodies. If you’re not familiar with her art, here she is talking about some of her recent work. On the Plush series Minter said,

Pubic hair has been erased in all of art history because it was deemed too vulgar. In 2014 I saw young girls were lasering off all of their pubic hair. So I decided to make pictures of beautiful pubic hair, representing all races and colours.

Art gets censored when it exposes the fault lines of power — works that confront dangerous subjects, taboos, things that we don’t want to talk about or acknowledge as problematic. By depicting parts of the female body rarely shown in art, Minter challenges powerful cultural ideals about beauty that women are so often expected to meet. And she pays the price for it.

One more brief example. This work by the textile artist Yvonne Iten-Scott, titled Origin, was banned from the American Quilters’ Society exhibition in Florida in 2024 because it was ‘representational of a part of a woman’s anatomy’. Was this censorship something to do with the politics of reproductive rights in a conservative State perhaps?

So it seems it’s a ‘no’ to pubes and wombs (or clitorises if that’s what you also saw) in art in the 21st century. Remove them from our view lest they force us to confront uncomfortable truths!

I can’t see anything graphic or violent about these artworks. In fact I would describe them as quite mild. What’s shocking isn’t the imagery per se, but how easily even the most restrained depictions of women’s bodies still manage to feel threatening to some people.

If you’re interested in seeing more examples of recently censored art (and you can’t get to the exhibition in New York) look through the Don’t Look Now website — it’s fascinating stuff. Honestly, I can’t quite believe what gets banned. As always I’d love to know your thoughts.

Three exhibitions I’d like to see

Monet and Venice, Brooklyn Museum, New York until 1 Feb 2026. Surely there’s nothing new to say about Monet? But like research on WWII, fresh perspectives keep coming. So, if you’re into Monet and/or Venice, get yourself a ticket to this mega-show.

Seeing Each Other: Portraits of Artists, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, England until 2 Nov. Last two weeks of this exhibit of portraits of artists by artists, from the early 20th century through pre-war modernism, pop art, the London School, and the YBAs. Rammed with big-name British artists. Plus a jolly nice day trip from London.

Lee Miller, Tate Britain, London until 15 Feb 2026. Comprehensive exhibition of Miller’s remarkable career from Vogue model to surrealist pioneer to WWII photographer, including her iconic self-portrait in Hitler’s bathtub. Unmissable IMHO.

Show Us What You’re Making

Share what you’re working on, thinking about, and creating! If you would like to introduce your art to The Gallery Companion’s readership, reply to this email with a short summary of what your work is about, where you’re based, and your links.

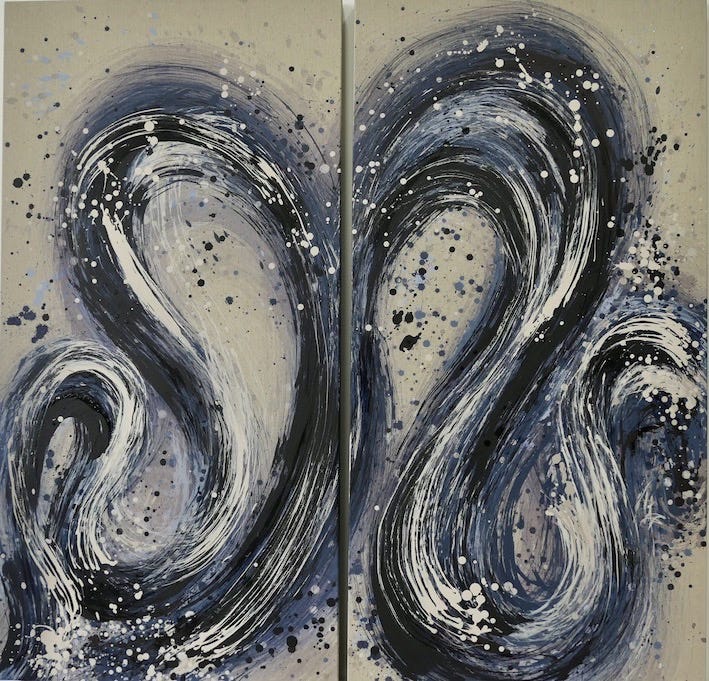

Caroline Banks is an Anglo-French artist based in London whose work explores the circularity of energy, time, and interconnectedness through expressive, calligraphic mark-making. Using the circle as a recurring motif, she reflects on life, death, regeneration, and collective unity in an era of division. Her dynamic yet contemplative works, often painted in gesso, ink, and acrylic, capture gesture, memory, and transformation. It’s beautiful stuff. On the work pictured above, Storm and Gloss, which she finished last week, Caroline said:

I draw one thing then see another: in this case a drawing of a dancer’s gesture becomes a painting reminding me of a watercourse. Painting with hand-made brushes reduces the level of precision: I’m operating from experience and skill yet also from the moment. Time is very important to me: its elasticity and depth which I express in the gesture.

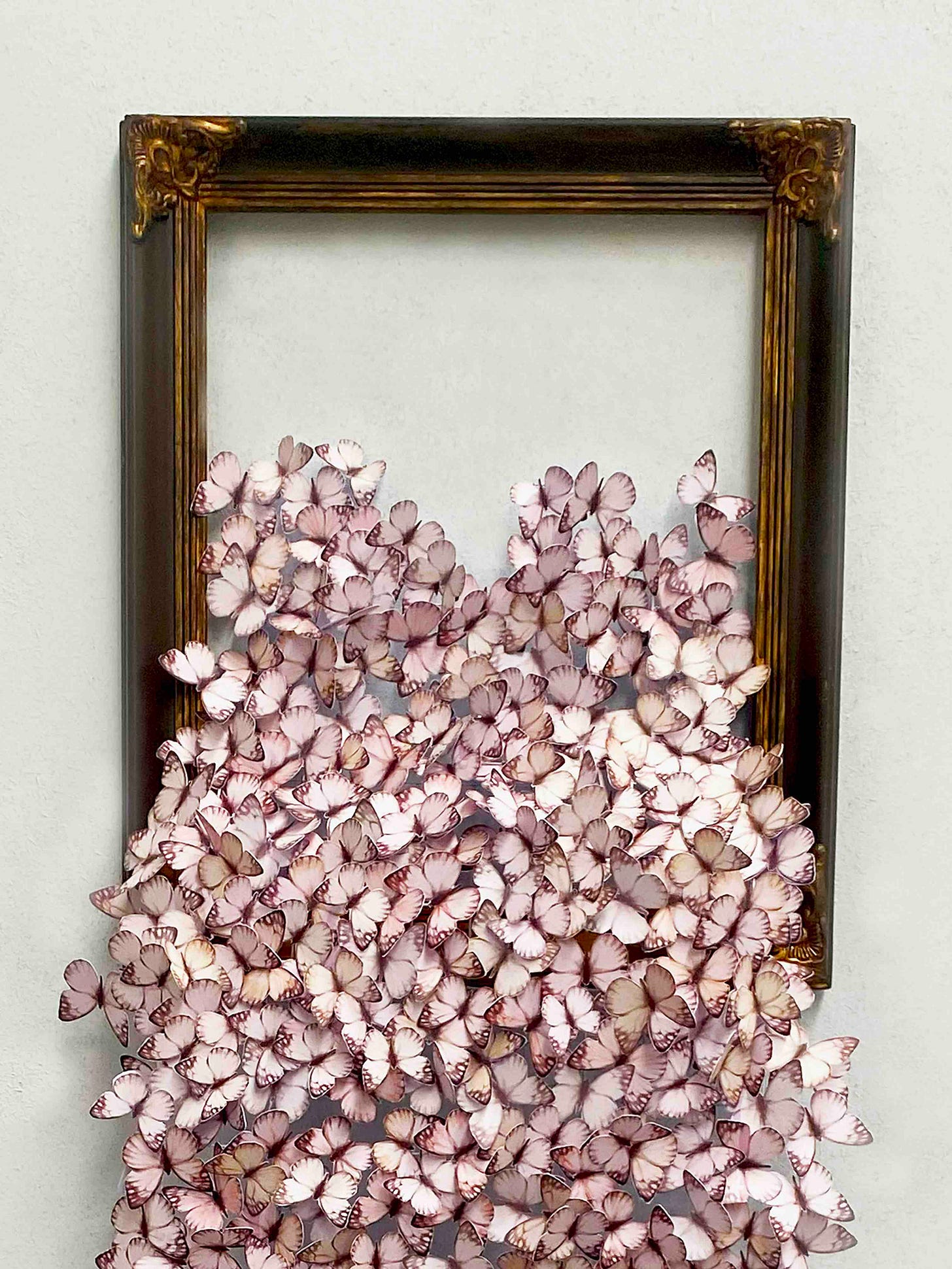

Jen Selmore is an Australian artist who uses recycled and vintage materials reminiscent of fabrics, textures and colour palettes from her childhood. Jen’s practice has evolved into what she calls paper entomology — using delicate, hand-drawn butterflies to explore serious social themes through small, beautiful, and seemingly fragile forms.

She recently completed this wonderful work, Living on Mute, which marks a shift for her away from social critique and nostalgia, toward something more hopeful. The work, a dense cluster of hand-drawn butterflies spilling from their frame, captures the moment of transformation that comes with self-acceptance and risk. Jen painstakingly made it over the course of a year, and it’s both a celebration of growth and the beginning of a new direction towards larger, more ambitious installations. Love it.

That’s all for today, GC readers.

Please help me spread the word about this newsletter by clicking like or restack. Or better still, share it with someone you think will enjoy what’s going on here.

Thanks for reading!

I don't like graffiti at all, and am particular about cathedral aesthetics, but I think this is brilliant and in perfect keeping with what christianity, and churches, are supposed to be: a home for the marginalised and voiceless. To bring these voices in and let them speak using a mode of artistic expression that is truly their own is the best thing I've seen in a long time and a powerful reminder of whom the church is supposed to be serving. That it makes pompous money-grubbing racists like JD Vance and Elon seethe is absolutely the cherry on the cake.

It’s amazing that Kim Kardashian's Skims just dropped thongs with fake pubic hair. Is more acceptable to the average person.And it’s all over the Inter Web and the media.But anytime you hang art of related subjects you get pushback from the public.