Women Taking Up Space

Visibility and the black female body in contemporary art

Today I want to tell you about an exhibition I saw at the Courtauld Gallery in London last weekend. It was a show of work by the British artist Claudette Johnson who makes large-scale drawings, mostly of black women. I’ve seen examples of her work before, but never in this quantity. She draws with pastel, which gives a lot of movement to her line and a richness of colour that makes it feel like the subjects are barely contained within the frame. Johnson describes these drawings as her attempt to ‘project the presence of the person’.

Like so many other black female artists Johnson’s work has only recently started to be properly recognised by the Art World establishment despite a decades-long career. She was born in 1959 in Manchester, the daughter of Caribbean immigrants, and began her career as a visual artist in the early 1980s. It was at that time she met other radical young artists including Lubaina Himid, Keith Piper, and Sonia Boyce who were beginning to explore issues of race and gender during a period of heightened racial tensions in the UK. These artists were founding members of the Black British Arts Movement, collaborating and exhibiting together against a backdrop of government rhetoric that was outspokenly anti-immigrant, when relations between the police and black and Asian communities were strained to breaking point, and at a time when fascism was on the rise.

In her work Johnson wanted to represent what she couldn’t see at that time either in contemporary art or in art from the past: images of people who looked like her. Instead of representations of slaves or maids, she wanted to put the presence of real black women back into the picture.

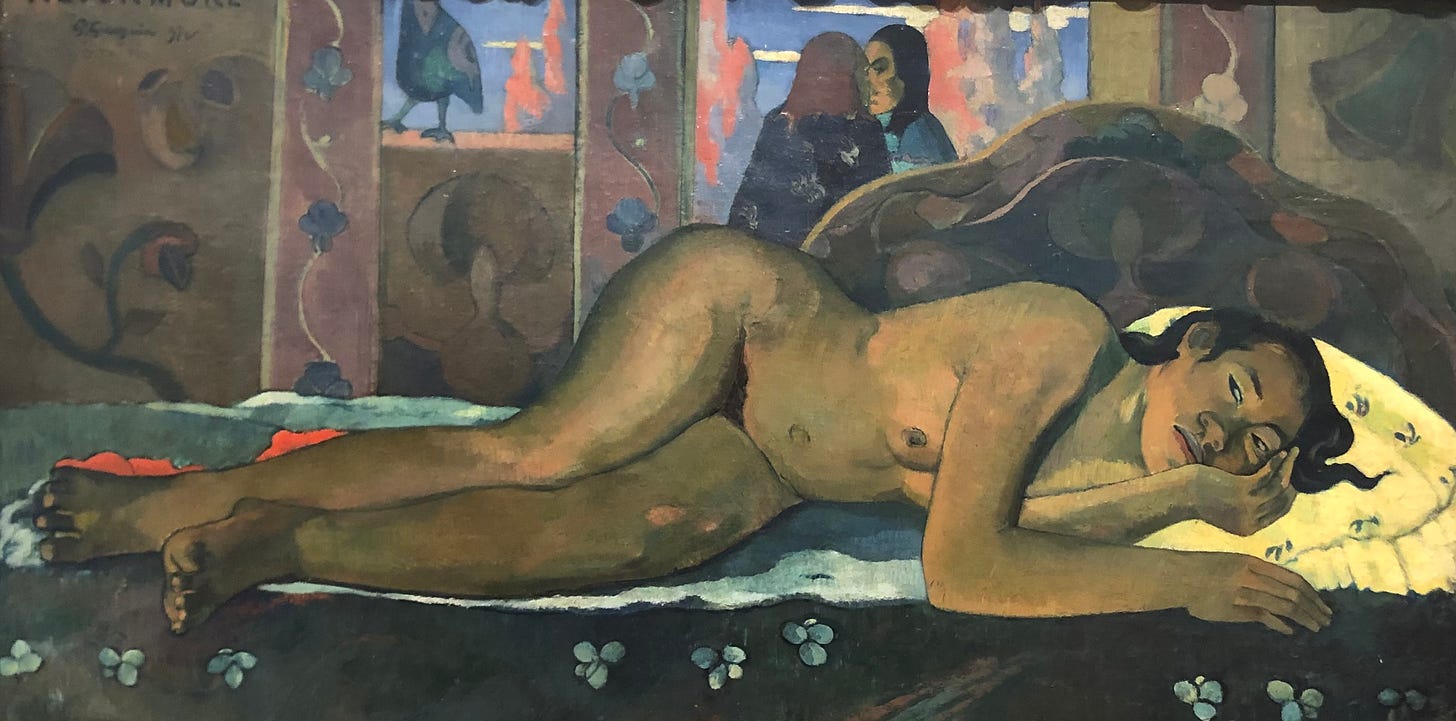

There’s so much to say about Johnson’s work, so many different directions I could go in. For a start, there’s her deep knowledge of modernist art and her feminist challenge to it which you can see in the visual references to Picasso and Gauguin in the drawings in this show. This is one of the reasons why the setting of the Courtauld Gallery, with its world-leading collection of 19th and early 20th century art, is so appropriate for an exhibition of her work.

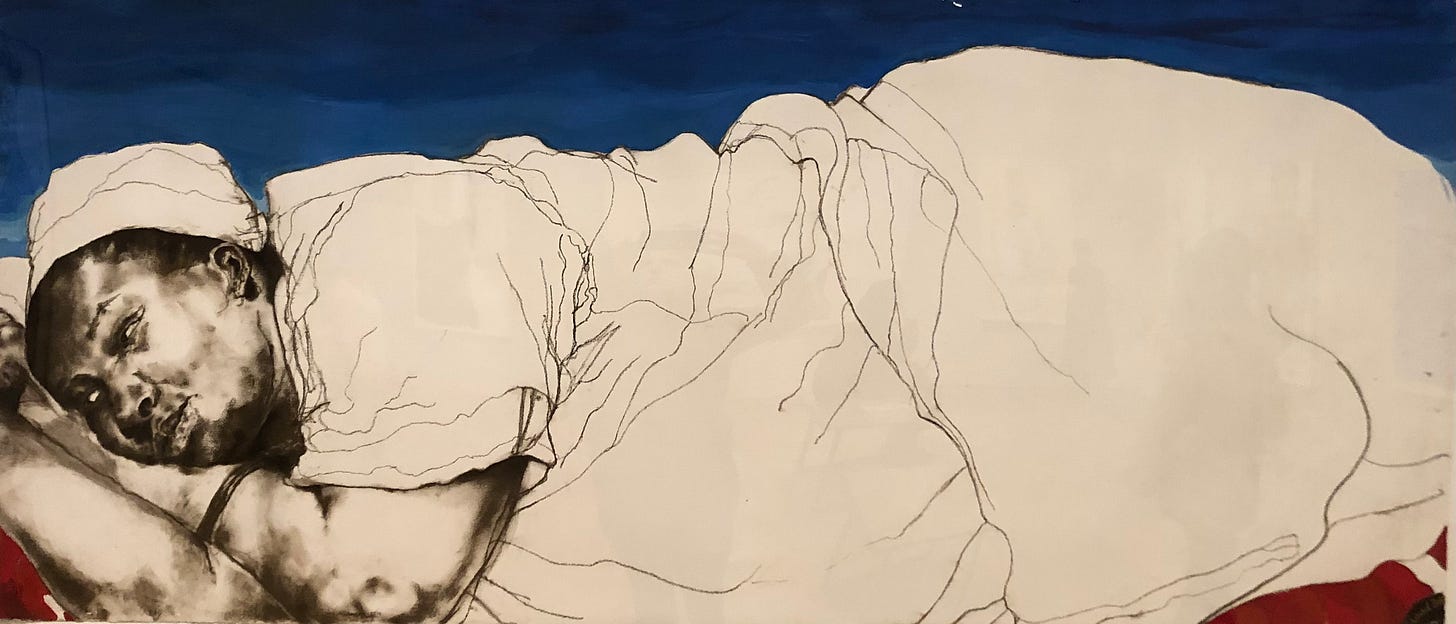

The contrast between her Reclining Figure (2017) and Gauguin’s 1897 painting Nevermore, which is an exoticised representation of a Tahitian female nude seen through a Western male gaze, strikes you harder when you’ve just walked past the actual nineteenth-century original.

Johnson’s drawing is based on a photo that reminded her of the position that her mother ‘would adopt in the evening when she was tired and would lay down on the sofa after a long day’. Her face is in focus, eyes not quite closed as though she’s still vigilant, heavy head resting on clasped hands; her body is clothed and left uncoloured, an empty white space on the huge horizontal canvas, delineated by just a few black pastel strokes. There’s nothing sexual or fetishised about this representation of the female body; instead, it communicates an insider’s understanding and empathy with the subject.

There’s also something about this artwork that speaks of the group of black women who are the undervalued and invisible backbone of our economy, low paid shift-workers, cleaners, care workers. Johnson’s work counters this invisibility. In her drawings the black female body uncompromisingly takes up space. One of the first works you see when you enter the exhibition is called Trilogy (Part Two) Woman in Black, in which the female figure is standing facing forward, staring defiantly out at the viewer, her arms raised and hands placed behind her head. She’s towering. Asserting her right to be there and to be seen.

Johnson’s work is partly about her own awareness of negotiating public space in a black female body. She talks about viewers entering into a space that is bound up with her experience as a first-generation daughter of Caribbean parents, growing up in a Britain that was only just getting used to the visible differences in a multicultural society. It was a place, she says, that didn’t quite know what to make of her. In one particularly moving account, Johnson vividly recalls an experience she had as a child in the 1960s:

I can remember sitting on a bus and my seat being the only one that was empty on a wet, rainy day in Manchester. The bus was crowded, people getting on, but the only space that was available was next to me. I was a child, but this woman did not want to sit down beside me. Maybe she had some other reason. But I felt it was this issue of not wanting to be up against a black person.

In this public space on the bus it’s as though Johnson was both hyper-visible and invisible at the same time. In contrast she describes the sense of liberation she felt on her first trip to Jamaica as a young woman, perceiving a freedom in the way people moved together. She says it was a place in which she didn’t detect any fear or revulsion coming at her from others:

This feeling of difference, the sense of shame Johnson describes about her experience of her body as she was growing up is not surprising given the hostile environment facing immigrants of the Windrush generation in Britain in the 1950s and 1960s. The historian David Olusoga has shown that despite immigration policy which encouraged workers from the Commonwealth to come and help rebuild Britain in the aftermath of World War II, a genuine welcome was only extended to those workers who were white. Successive governments after the British Nationality Act of 1948 fretted about what they regarded as the threat posed by black and Asian immigrants to the British way of life and its cultural cohesion.

Narratives about immigrants as cheats and lazy scroungers coming to the Motherland to take advantage of the new welfare state system dates back to this era. Politicians including Winston Churchill and Enoch Powell stoked public fears with rhetoric that contributed to an atmosphere of open public hostility and racism towards black British citizens. Many of the Windrush generation recall being shouted and spat at by white people, chased off the streets, and told to ‘go home’.

Like Claudette Johnson, Barbara Walker explores ideas about the marginalisation and invisibility of the black subject in the history of art. I first saw her work a few weeks ago in the excellent exhibition currently on show at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. It’s about this museum’s relationship with the history of slavery and explores how the historic objects and images in its collection were made to shape and reinforce societal attitudes of prejudice and racism. Walker’s work addresses the erasure of black lives within European visual culture by reproducing old paintings that mask out everything except the black figures.

This year Walker has also been shortlisted for the prestigious Turner Prize for her recent work about the Windrush scandal. Many readers will be familiar with this sorry story which began in 2012 when the so-called ‘Hostile Environment Policy’ was first introduced by the current British government. This policy implemented legal and administrative measures to make it more difficult for illegal immigrants to live and work in the UK. Thousands of people who had legitimately moved to Britain from the Caribbean in the post-war years before 1973 faced being kicked out of housing, fired from their jobs and prevented from accessing healthcare because they were unable to prove their citizenship. Some were even detained by the authorities and deported. This was surely the apotheosis of the continued call over the decades to ‘send them all back where they came from’, ignoring the uncomfortable truth that ‘they’ come from down the road.

Walker’s body of drawings for the Turner Prize, which she has called Burden of Proof, is a powerful statement about the distressing process that thousands of black British people were subjected to by the UK Home Office in order to ‘prove’ their right to remain in their own country. Those caught up in the scandal were required to submit several official documents from every year that they had lived in Britain, some dating back 60 years and more.

On top of meticulously hand-copied facsimiles of documents Walker has drawn portraits of real people whose lives have been turned upside down by this policy. Walker describes them as ‘mundane documents’ that have become ‘oppressive instruments to prove legitimacy.’ In the layering of imagery and words, the person and document, Walker challenges the viewer to think about how our systems reduce down the individual to the dehumanising level of administrative box-ticking and paper-pushing. She has translated the portraits from these smaller works on paper to a monumental scale on the walls of the gallery. In this way she brings the powerless who were quietly being erased behind the scenes back into view in a very visible way.

Like Claudette Johnson, Barbara Walker talks about her work as being partly about her own visibility as a black woman. It brings to mind a story that the actor Coco Sarel told a few months ago on her brilliant podcast Closet Confessions, which she co-hosts with the writer Candice Brathwaite. In this show Sarel and Candice discuss the realities of their lives as dark-skinned black British women and what they constantly have to bring to be seen and heard in the world and to carve out legitimate space for themselves.

In this episode Sarel describes how her elderly mother had recently gone on a journey on public transport across London with a young white female friend. Usually her mother is ‘fighting her luggage’ on the Tube, but on this occasion men were tripping over themselves to help her. It was a revelation to her to experience it differently with the presence of her companion; normally, unless she specifically asks for help, it’s almost as though she doesn’t exist.

Of course there are many reasons for this. It’s partly the invisibility of all older women, but as Candice suggests it’s also perhaps partly about the kind of energy you give out when you don’t truly believe you have the right to take up space. That energy comes from years of socialisation in attitudes that are threaded right through our culture, and have a long history. How we as a society undo that is a good question, and it’s a task that feels almost impossible at times.

As always I’d love to know your thoughts on any of these artists and ideas so please click on the comment button below to leave a message.

I just watched both linked videos and so appreciate hearing these artists’ perspectives. Their messages are so powerful and important. Learning about the black experience (in the UK and USA) has been so enlightening and enraging, especially realizing how sheltered many (most?) white people are from it by design. These amazing women are doing the social, political, and cathartic work (beautifully and skillfully) that will truly change the world for the better. At least I hope. Thank you for shining a light on them and bringing them into my schema.

Is the exhibition at the Courtauld still on (I'm googling) but it looks fantastic. Thank you so much for this, I hadn't heard of either of these artists before. The Gospel Oak letter is heartbreaking