What's The Point in Looking at Cezanne Now?

The blockbuster exhibition at Tate Modern made me wonder

Last week I went to see the Cezanne exhibition at Tate Modern, along with half of London it seemed. Paul Cezanne (1839-1906) was an important artist in the development of modern art, and his work straddled the French impressionist and post-impressionist movements. If you’re not familiar with Cezanne’s art, a visit to this show will leave you thoroughly saturated by the end. It’s a huge exhibition, and the curators provide lots of information about his life and times, his pioneering exploration of perception, colour, form, his uncertainties, his influence on later artists etc.

But there’s not much in this show about Cezanne that I haven’t heard before. So I found myself asking what is the point of looking at Cezanne’s art in so much detail now, in 2022? What else can we learn from him?

Perhaps it doesn’t matter because it’s just a real joy to see lots of Cezanne’s art all together like this and to be able to trace the development of his ideas and experiments over time. Saying that, I’m an art history geek. And I wondered as I looked at my fellow gallery companions drifting through this almost endless show alongside me, how many of them still cared after the umpteenth study of apples in a bowl or yet another slightly different view of Mont Sainte Victoire? How many were secretly thinking, when is this show going to end?

There was one painting, however, that stood out for me and made me think about something other than those standard Cezanne stories. In 1866, when he was in his mid-20s, Cezanne painted a representation of a black man sitting on a stool, leaning over a bale of cotton. He called the painting Scipio. It’s not an artwork I’ve seen before, and it took me by surprise given that most of Cezanne’s subject matter (mountains, apples, trees etc) is definitely not in-yer-face political.

Scipio was a model at the Academie Suisse where Cezanne studied art when he moved to Paris. France had abolished slavery throughout its empire twenty years before, but it was still a hot global topic in 1866 when Cezanne started painting this portrait: just the year before, in 1865, slavery had been abolished in the USA with the end of the American Civil War.

Cruelty is the subject of this painting. Scipio’s back is the main focus. Cezanne painted the texture of his skin with thick layers of paint to give emphasis to the flesh. There are diagonal striations coming down from Scipio’s spine, and pink blotches are visible amidst the dark brown of his skin. It’s raw and whiplashed. There’s something submissive and hopeless about Scipio’s face and his elongated, drooping, almost lifeless hand.

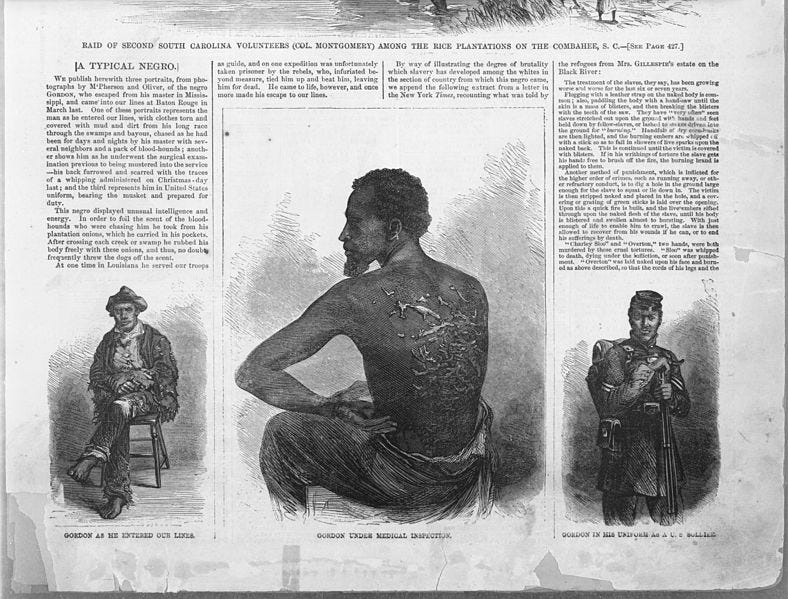

In the exhibition’s notes the contemporary artist Ellen Gallagher connects this painting with the widely circulated image of Gordon, an enslaved man whose story was told by American abolitionists in newspapers in the 1860s. It was reprinted in publications around the world. Gordon’s back is a mesh of keloid scarring. This particular illustration, which featured in Harper’s Weekly in July 1863 with the description ‘A Typical Negro’, was created from a photograph.

But Cezanne’s Scipio doesn’t just tell us about abolitionism. It also tells us about the development of new technologies in the nineteenth century that enabled the rapid dissemination of imagery across the world. New printing processes resulted in illustrations appearing in newspapers for the first time from the 1830s. And the invention of photography in 1839 quickly led to cheap reproductions which could also be developed into etched illustrations for newspaper articles, like this one.

The power of political persuasion through image-making therefore took on a new significance by the middle of the nineteenth century. This portrait is evidence of that. Perhaps Cezanne had noticed scarring on the back of the Academie Suisse model; more likely he had seen imagery in an illustrated periodical or newspaper that had inspired this painting.

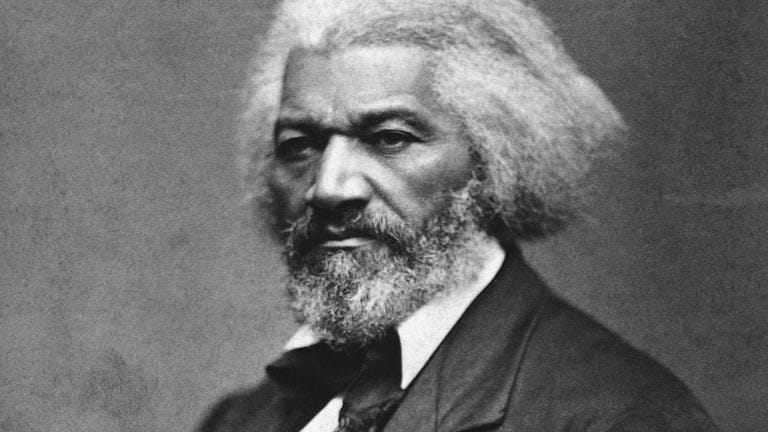

Image-making as an essential aspect of political campaigning all started back in Cezanne’s day. His portrait of Scipio demonstrates how alert the abolitionists were to the power of images. The visionary African American freedom-fighter Frederick Douglass, who was born into slavery in the USA, knew that pictures allowed him to present himself as someone worthy of respect and dignity, that they had the power to influence and change minds about slavery.

In his Lecture on Pictures from 1861, Douglass expressed his vision of how picture-making and photography could offer powerful tools in the fight for social justice and equal human rights for all. He was the most photographed American in the 19th century (and he is the subject of a recent multi-screen film installation Lessons of the Hour by the brilliant British artist and filmmaker Isaac Julien).

Cezanne’s art is in a broad sense about endlessly shifting perceptions and the construction of images, and that makes his work very relevant to us now given the power that the image-saturated media has in our culture.

This show has been getting 5 star rave reviews from the art critics and it’s not surprising given the feast for the eyes on display here. But in my opinion the best exhibitions of art from the past very gently nudge viewers towards connections we can make to our own experiences. Cezanne’s Scipio painting and the short blurb on the wall that accompanied it got me really intrigued and hungry to find out more. And for me there wasn’t enough of that in this show.

Ooh this post is so interesting! I have always struggled with Cezanne. Studying art history we learnt about his work forming the bridge between late 19th century blurry Impressionism and the early 20th century wacky weirdness of Cubism. And I honestly revere and respect him for this. But (brace yourselves) I have never actually liked his work and honestly don't know if I would have made it to the end of this vast exhibition! That said, I have never seen his painting of Scipio and it most likely would've stopped me in my tracks as it did for you Victoria. Loved hearing your thoughts on it and wish I could've walked through the exhibition by your side. It will happen one day! Right, now I'm off to look up Isaac Julien's "Lessons of the Hour" 😊

This is so great. I don’t think I’ve ever read anything that place Cezanne in any context except an art-historical one. His work always seems to be presented as sui generis. But of course he was a person in a world as complex as ours and was inevitably influenced by it.

The Cezanne portraits show in New York a few years ago surfaced some really interesting works that I’d never seen before. And there wasn’t an orange among them.