Uncertainty Is Essential: It's How We Make Sense of the World

The US midterms, William Kentridge's apartheid-era art, and finding hope from history

I often find hope in the precariousness of our present day by turning to history and looking at what has happened in the past. There’s a precedent for most scenarios.

Yesterday Americans cast their votes in the midterm elections, the results of which politicians and commentators have been warning could be catastrophic for political stability in the US. Democracy is under threat with the rise of the Far Right. The rhetoric of hate is prevalent in public discourse. Guns are everywhere. And with the memory of the attack on the US Capitol on January 6 2021 still fresh, it feels like a tinderbox situation.

The majority of Republican candidates running for office in this race are election deniers, and more than half of those are expected to win their seats. It remains to be seen whether the rest will accept the results if they lose. The reality is that election deniers don’t care about people’s rights because they don’t hold themselves accountable to voters. When politicians who don’t respect the results of the ballot box are in charge, we’re in the realms of authoritarianism.

For people who follow American politics closely, the uncertainty of the US midterms is unsettling to say the least because it has not only domestic but also international implications. Who steps into the breach as the bastion of democracy when the USA is no longer able to be?

But we have been here before. In the 1930s and early 1940s sitting members of Congress were involved in a plot to overthrow the US government, and far right insurrectionists, inspired by the Nazis in Germany, were criminally charged with plotting to end democracy.

If you haven’t yet listened to the podcast series Ultra by the American journalist Rachel Maddow I would highly recommend it. She grippingly narrates the true story of the battle for democracy in the years before the Second World War. It was an eye-opener to learn about this particular chapter in American history given that the dominant narratives of WWII are about the heroic involvement of the USA in the defeat of the Far Right in Europe.

American extremism is nothing new, and back then the forces of fascism did not prevail. Of course the context is different now, but it does nevertheless give me some hope that democracy will win through in the end.

With all these ideas swirling around my mind, I recently went to see the William Kentridge retrospective at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. And boy! did his art make me think.

Kentridge is one of South Africa’s most important contemporary artists. Born in 1955 in Johannesburg, he grew up during the apartheid era when the country was dominated socially, politically and economically by the minority white population. Kentridge is best known for his charcoal drawings and animated films, but he also works with tapestry, sculpture and prints, and in theatre and opera.

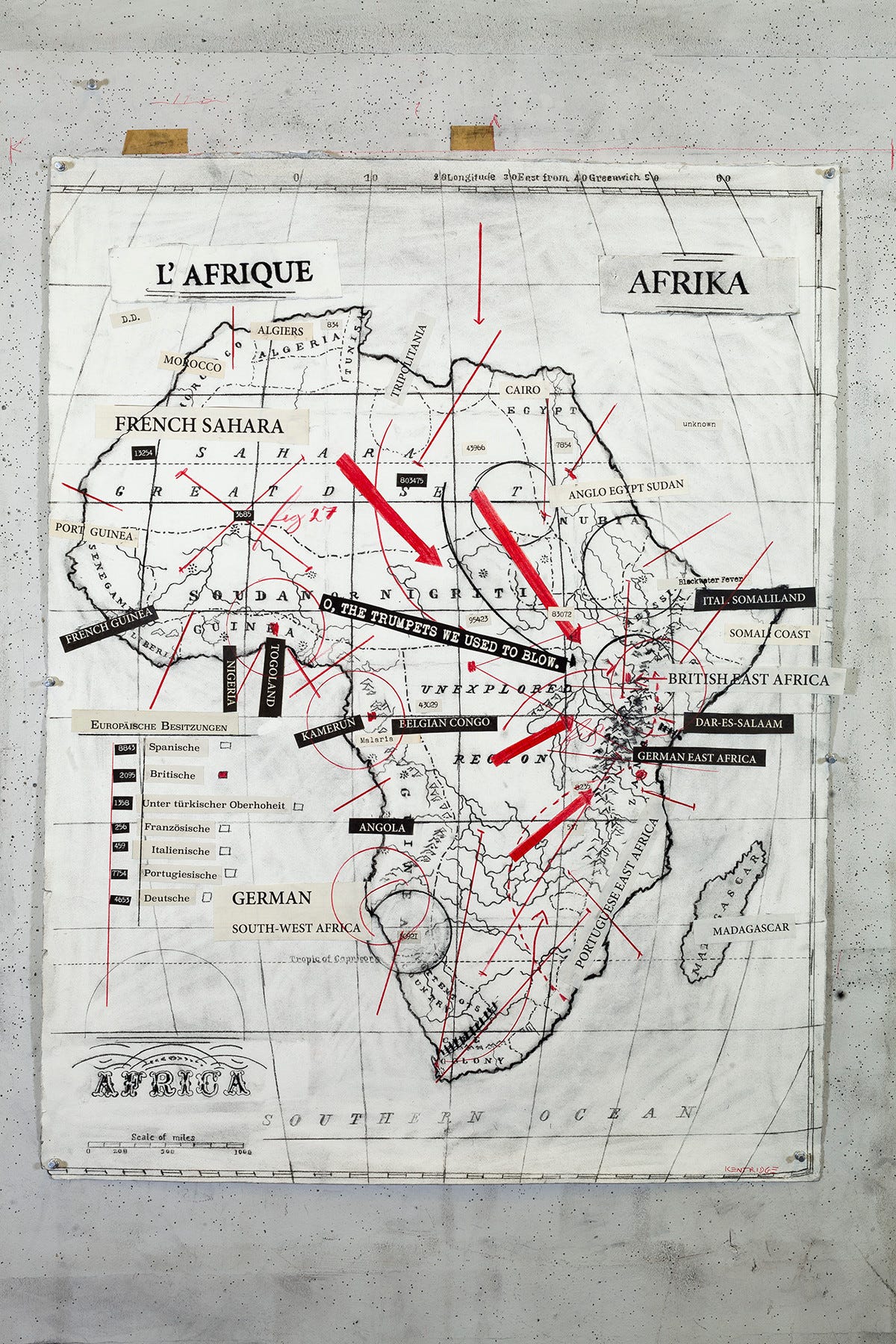

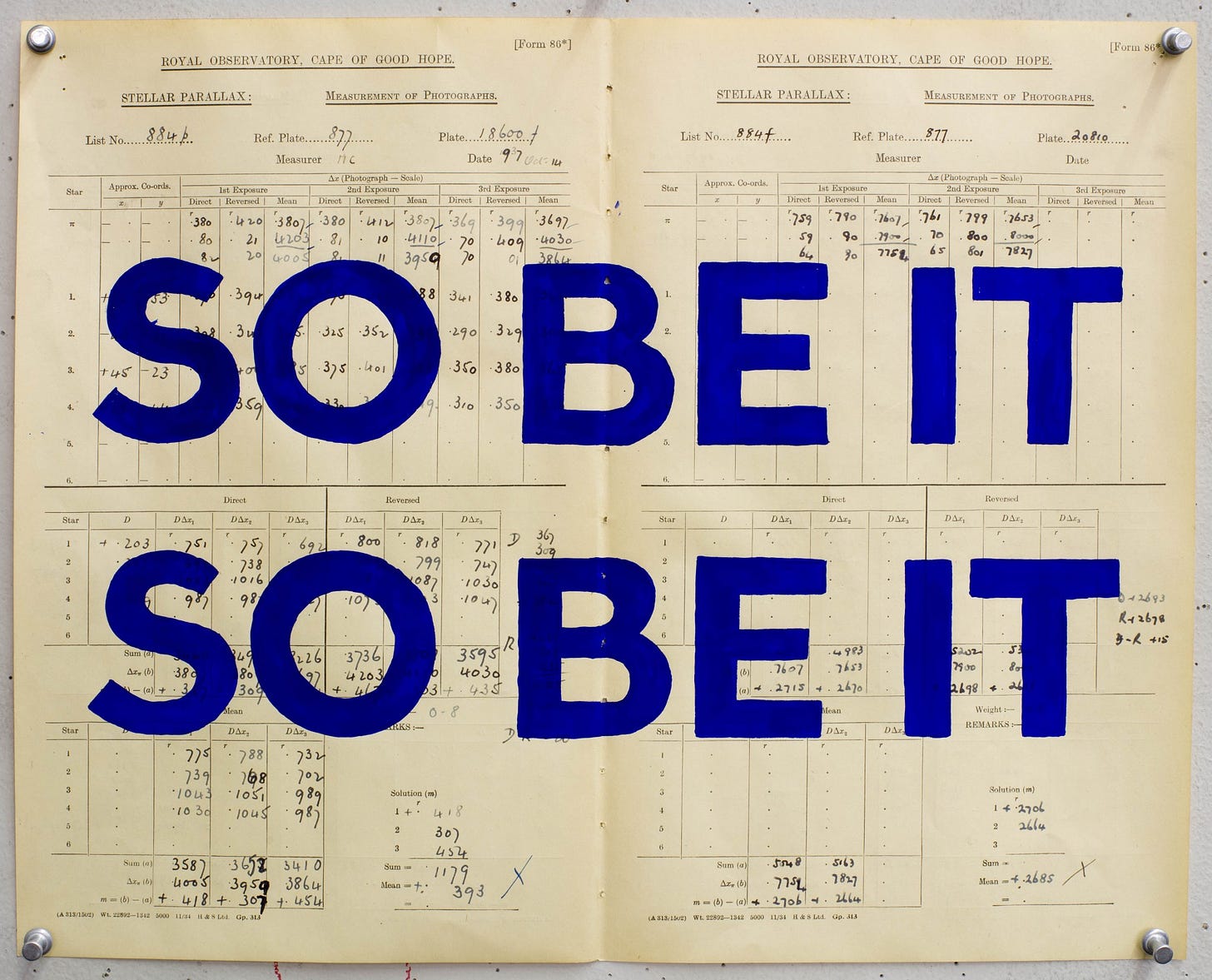

At university in the 1970s Kentridge studied political science and African history, and his work is infused with the knowledge and understanding that histories are both shameful and heroic. His art is often clearly political in its subject matter, such as this map of Africa divided up arbitrarily by lines and markers by the nineteenth-century European colonial powers. It is part of his Colonial Landscapes series of drawings from the mid-1990s based on the two volume book Africa and Its Explorations As Told By Its Explorers (1891) which reflects the European belief in their cultural superiority.

Kentridge’s short animated films are mesmerising, and remind me of early black and white Mickey Mouse Disney cartoons where you can really see the labour of the artist’s hand in the unpolished animation. The first film Kentridge made in 1989 was a story about a fictitious ruthless industrialist called Soho Eckstein, who buys up most of Johannesburg as real estate and exploits black workers to build his empire.

The characters of this early film run through many of his later films, including in The History of the Main Complaint (1996), which was a response to the public testimonies heard in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings that investigated the atrocities of the apartheid era. In this short clip Kentridge talks about the ideas in this particular film, and it gives you a sense of what his animations are like:

At one level you can read his films as a crushing commentary on the white supremacist politics of South Africa in the apartheid era. But there’s meaning on another level in all of Kentridge’s films, in the philosophy behind his process of making art. He constructs his films by drawing on paper using charcoal that he then photographs before rubbing out part of the drawing and changing it slightly, rephotographing it, rubbing it out and redrawing again, and so on. It’s a laborious process. Kentridge calls it ‘Stone Age film-making’.

That hand-made process creates an uncertainty in his images and a constant shifting of views in the film. I don’t know how to express the experience of watching it other than to describe that uncertainty as ‘palpable’. Kentridge has talked about how he is interested in ideas about the process of how we think, how we take fragments and re-interpret them retrospectively to make sense of the world. Back in 2014 he said this:

Uncertainty is an essential category. As soon as one gets certain their voice gets louder, more authoritarian and authoritative and to defend themselves they will bring an army and guns to stand next to them to hold. There is a desperation in all certainty. The category of political uncertainty, philosophical uncertainty, uncertainty of images is much closer to how the world is.

Seeing Trump call in his far-right violent extremist groups to the Capitol last year, and hearing reports of vigilantes intimidating with their guns at polling stations, these words relevantly speak to this political moment. So I’m going to embrace uncertainty, and long may it continue, because the alternative cannot be the option.

There’s so much more to say about William Kentridge’s art, and I’ll return to it again in future posts. If you’re in the UK and you’re able to get to the exhibition at the Royal Academy before it closes in December I would strongly recommend that you do. It is one of the best exhibitions of contemporary art that I have ever seen, and that’s partly because of his thought-provoking, visually stunning work. But he was also heavily involved in the hanging and curating of the exhibition, and it shows.

If you can’t get to the exhibition I suggest spending some time on his website because there’s loads of his work on there, and tons of videos of him talking about art and ideas. He’s just simply a brilliant artist.

I’ve enjoyed taking a look at Kentridges work this week, thank you for the introduction ☺️. I’m unlikely to get to London before the end of the year but the exhibition looks epic.

I find his work really multidimensional, so much going on in each piece. Theres an interesting contrast between the gnarly films with distorted movements from the rubbing out and /redrawing and the image of the Comrade Tree collage for example. I think it’s the ugliness that sits with nature that makes me think of dystopia/handmaids tale. He’s presenting all of these pieces, his lens of the world, as individual scenes - but you know that they are all based on one lived context.

The colonial landscapes feel like they’ve been washed in a distorting ‘film noir’ filter.

The image of the woman waving the big red flag 🚩 on the gallery website made me think of ‘les mis’ and revolution, yet that image of Black Box/chambre Noir’ made me instantly think of the popular TV version of Atwoods handmaids tail when I entered the webpage!

This was a fantastic piece, and Kentridge's work is incredible! I want to see it in person. I don't know if you follow Ray Dalio, but most disturbingly he methodically lays out the statistical probability of an impending civil war due to all the reasons you mention re: polarization and the fact that the Supreme Court for the first time has rulings that are/will be disobeyed (abortion & gun control). But back to art, I keep thinking of that quote from The Third Man about all the art that came out of the Borgia's reign of terror and bloodshed.