Reading the Riot Art

Alternative representations of civil unrest

Twenty years ago the French street artist JR began a photographic project called Portrait of a Generation with his friend, the film-maker Ladj Ly. It was JR’s first major project in a career that has seen him become one of France’s leading contemporary artists. Back then both young men were full of hope about making change happen in the marginalised Parisian communities where they had grown up, and with this project they wanted to create a body of work that communicated alternative narratives and representations of their friends and families.

JR was brought up in the concrete jungle of housing estates on the outskirts of Paris, far from the city’s middle-class central districts. Ladj was also from one of these Parisian suburbs, Les Bosquets, a community largely made up of people from African descent living in run-down tower blocks. At that time these were neighbourhoods with many underlying problems and social issues that had gone unaddressed over the years. Huge tensions had been building up in the local population due to limited education options, poor employment opportunities, lack of transport infrastructure, and bad community relations with the police.

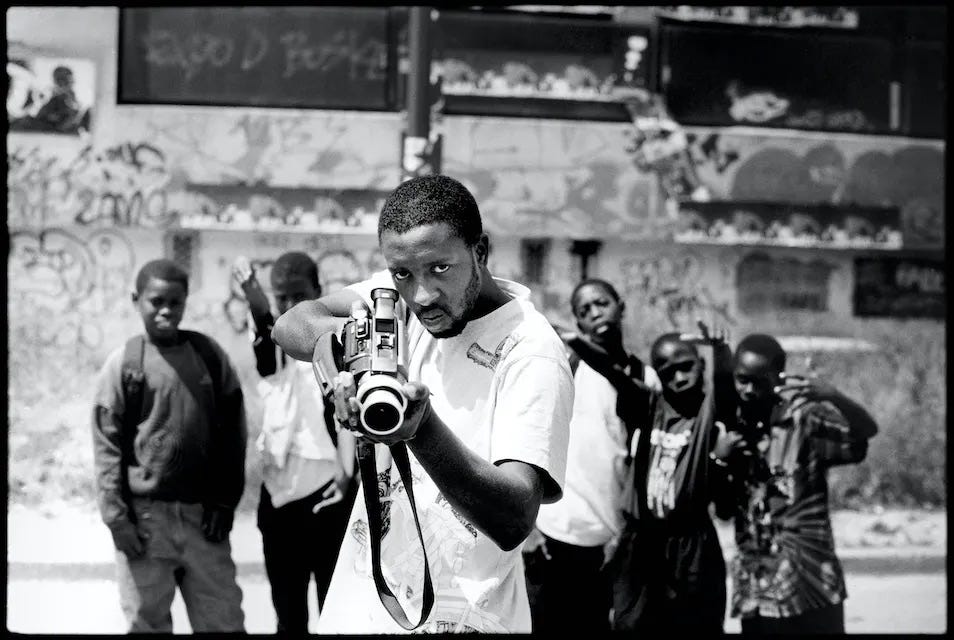

The two friends made their first portraits for the series in Les Bosquets in 2004, taking close-up images of its young inhabitants, who played to the cameras and pulled silly faces. In one striking black and white photo Ladj is standing in the foreground pointing what looks like a gun straight out at the viewer, his eyes intensely locked on you, his mouth screwed up tightly in a grimace. In the background stands a crowd of kids, slightly out of focus, striking street-style poses.

It’s a scene that could be interpreted as threatening, except on closer inspection you notice that the gun is actually a video camera, and the kids have cheeky smiles on their faces. They can’t hide their enjoyment of the situation. It’s a perfectly-framed, brilliant photo that aimed to provoke French viewers to question their assumptions about young Black people from the suburbs.

Instead of seeing wild criminals, they might see youngsters with aspirations, creative ideas, agency, and tongue-in-cheek humour. And the photo communicates something about their desire to tell their own stories and to choose how they present themselves in the face of negative media representation. JR printed up their images on big posters and pasted them on walls around the neighbourhood, giving these young people a sense of ownership and self-worth through visibility.

The following year, in October 2005, Les Bosquets exploded in riots after the deaths of two teenagers who had tried to hide in an electricity substation whilst being chased by the police. The violence quickly spread through Paris and beyond. Over the course of a month rioters burned nearly 9,000 cars across France, ransacked buildings and looted shops. The media coverage ramped up fears about out-of-control immigrant youths, the public was outraged and fearful, and politicians condemned the rioters.

I’ve been thinking about this particular photo and JR’s project in Les Bosquets this past week as riots have again erupted in the Paris suburbs and have spread across France. This time the triggering event was the death of a 17 year-old boy, Nahel Merzouk. Footage shows him being shot at point blank range by a policeman after being pulled over in a routine traffic stop in the suburb of Nanterre. The collective complaint of the rioters is once again about the level of police violence and harassment against members of their community, and more broadly the crippling discrimination they experience in French society.

The carnage of the 2023 riot mirrors that of 2005, as does the response from politicians, who have been passing blame again. Over the last few days I’ve heard French politicians claim that it’s the parents’ fault for not controlling their unruly children (some as young as 13 out on the streets); that these lazy and entitled youths should be applying themselves at school instead and developing a good work ethic; that they have been playing too many video games; that their behaviour demonstrates an ingratitude for the help they have been given, and if they don’t like it here they can go back to their own countries. The young people involved in these riots have been described by politicians as ‘vermin’, as ‘flocks of sheep’, as ‘zombies’, and as the ‘mindless mob’ who are out for cheap thrills and opportunistic looting. Essentially they are mad and bad people out of control on the streets.

There have undoubtedly been hooligans operating in the crowds of rioters. But political explanations of riots that reduce them down to criminality alone deflects from serious engagement with what is actually going on. A 2019 report published by Sussex University looking into the causes and spread of the riots in London and across Britain in the summer of 2011 challenges the established view of riots as meaningless mob mentality. One of the report’s authors, Stephen Reicher, Professor of Psychology at the University of St Andrews argues that if we take crowds seriously we will ‘learn a hell of a lot about what’s wrong in our society and what we need to put right.’ The three-part podcast series in which the authors discuss their findings is a fascinating listen.

The report argues that nearly all crowd behaviour is meaningful. Only certain people get drawn into riots, only in certain geographical areas, and only certain targets are attacked. Riots speak of the psychology of the powerless and how social identities can drive patterns of collective action that enable them to reverse power relations, if only temporarily. And crowd events aren’t just about the crowd, they are also interactions with the police. There is a dynamic at play in the meeting of both sides, which has an impact on behaviour and whether violence escalates.

What stands out in this study is just how complex the causes of riots are, how there are no simple explanations. The intensifying use of the police stop and search policy in the months leading up to the summer of 2011 was the foundation on which people were able to coalesce an identity that enabled them to oppose the police in the first stages of the riots. And the initial police interventions amplified the situation, enabling an agency to emerge that underpinned the capacity of those riots to spread.

Clearly good relations between police and communities are fundamentally important for social order. But the authors argue that the history of riots has shown that this is not only about policing. Structural factors like poverty and deprivation, racism, and restricted access to wealth and resources, are all part of the complex mix. Riots don’t happen without at least some of these elements.

All of this made me think about the film Handsworth Songs by John Akomfrah, the artist and film-maker who has been commissioned to represent Britain at the Venice Biennale next year. Akomfrah began his career in the early 1980s as part of the Black Audio Film Collective, a group of artists who were exploring what it meant to be Black and British at a time when the country was in the midst of a race relations crisis: Thatcher’s government was pursuing an anti-immigration agenda, the far-right British National Party was on the rise, unemployment was high, and there were severe tensions between police and Black and Asian communities.

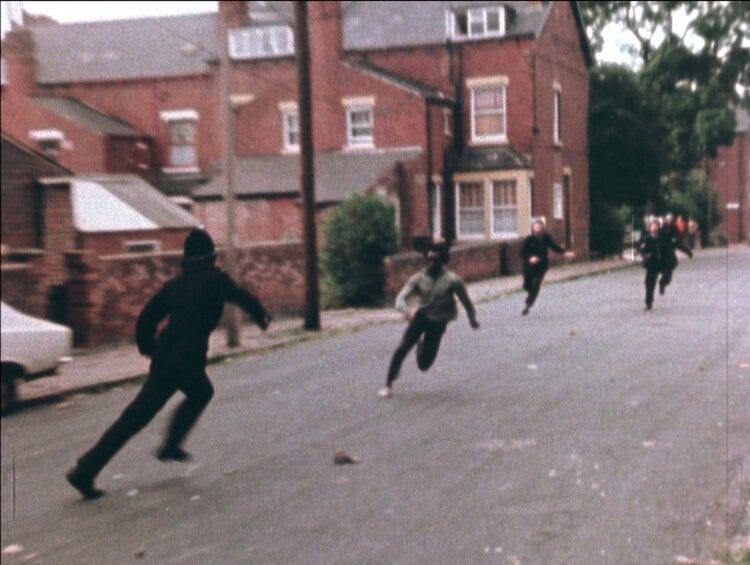

In this social context John Akomfrah directed Handsworth Songs in 1986, a defiant and thought-provoking documentary about the riots that had taken place in Birmingham the year before. Tensions over police harassment and brutality had reached such a pitch that one particular arrest triggered riots in which hundreds of young Black youths attacked police and destroyed property in their neighbourhood. Many politicians and media outlets condemned the rioters as criminals, suggesting that they were copying civil disorder in London and elsewhere because they were bored.

I’ve seen this film a couple of times in my life, but I watched it again this week with fresh eyes and new thinking. It’s an extraordinary, richly-layered depiction of the Birmingham community, and brings together archival footage of the Windrush generation, media coverage of the riots, poetry, music and interviews with local residents. The heavy presence of the police dominates the film.

Handsworth Songs is a visual text in which geographical context is important, both in its focus on the Birmingham riots in the 1980s and in its exploration of the history of Black migration to the UK in the 1950s and 60s. But it also points to a broader pattern of struggles faced by ethnic minority communities across time and place. All the ingredients that we see in other riots are there: economic disadvantage, social exclusion, and heavy-handed policing strategies.

What I love about Handsworth Songs is that it is art as a record of resistance and solidarity. But it also clearly demonstrates the ways art challenges mainstream narratives and offers alternative perspectives, presenting the viewer with the complexities of race, power, and representation rather than a simplistic reduction. In this sense it makes me think of the great 1967 masterpiece by the American artist Faith Ringgold, #20 from her American People Series.

In this painting Ringgold depicts a violent scene from a civil rights protest she had found herself caught up in during the summer of 1967. The image shows both White and Black bleeding bodies strewn across the canvas, everyone is affected by the struggle, no one gets out of it unscathed. It’s a representation of the dynamics of power and the ways in which Black and White Americans were locked in that struggle together. Ringgold’s work speaks to an idea that Martin Luther King Jr had written about in his Letter from Birmingham Jail, which he wrote in 1963 while he was imprisoned for participating in civil rights demonstrations. He said,

We are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.

In other words, we all have a responsibility to one another, our lives are interconnected. The struggle for equality must be a collective endeavour and will benefit everyone in society as a whole.

A year after the French riots in 2005, JR returned to the suburban neighbourhood of Les Bosquets to continue his photographic project Portrait of a Generation. Although he was conscious that the subjects of his photos weren’t all squeaky clean and angelic, he nevertheless wanted to challenge the idea that the young people of this neighbourhood were ‘scum’, a term the French Minister of the Interior had used to describe the rioters.

JR took close-up, full-frame face portraits of the neighbourhood residents pulling distorted faces to caricature themselves. And then he pasted them up on enlarged posters all around Paris. On each poster was the person’s name and address. It was an attempt once again to question entrenched ideas by bringing the individual back into the picture. Here is a real person, this is their name and where they live.

I’m not saying art’s the answer to the deep social problems in France by any stretch, of course it’s not. But art does have the gentle power to move people towards a different position through language that is beyond words. Artists like JR, John Akomfrah and Faith Ringgold put art to work in service of us, to remind us of the things we have in common. And this is something that often seems absent from difficult political discussions that increasingly seem to polarise us.

As always I’d love to know what you think about these artists and any of these ideas. And please share any other artists whose work is relevant to this theme in the comments.

I’ve also read another thoughtful post this morning on Substack about both this sad death and the reason behind the riots -- linking below.

JR’s art is a beautiful form of passive resistance (on the words of MLK). I wonder what will make these politicians listen. Art is one way to attempt for them to feel the meaning of having this existence in France. Really interesting to see the art from the 60s and the way it affects us all. Thanks for writing about this.

https://open.substack.com/pub/hannahmeltzer/p/refusal-to-comply?r=rtf40&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post

One of my favorite MLK quotes is: A riot is the language of the unheard.

It's a rich statement.