Inside the Creative Mind

Sketchbooks, gunpowder art, Giorgio Armani and more!

Coming up this week in The Gallery Companion:

First up, I’m introducing a new feature — a spotlight on the work of artists from The Gallery Companion’s readership. My emails go out to thousands of readers around the world, both artists and art lovers. So if you would like to introduce your work to this readership, reply to this email with a short summary of what it’s all about, where you’re based, and your links.

What else? I’ve been thinking about the value of sketchbooks to artists, inspired by GC reader Ann Pham’s sketches.

And in response to Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang’s recent controversial Rising Dragon firework piece I’ve got some questions about the ethics of making art today.

Plus my list of must-see international exhibitions and news from Gallery Companion readers from around the world.

Some thoughts on artists’s sketchbooks

Hearing an artist talk about their ideas and the process of making, and seeing those ideas gradually emerge in visual form in sketchbooks, is where the magic of art lies for me.

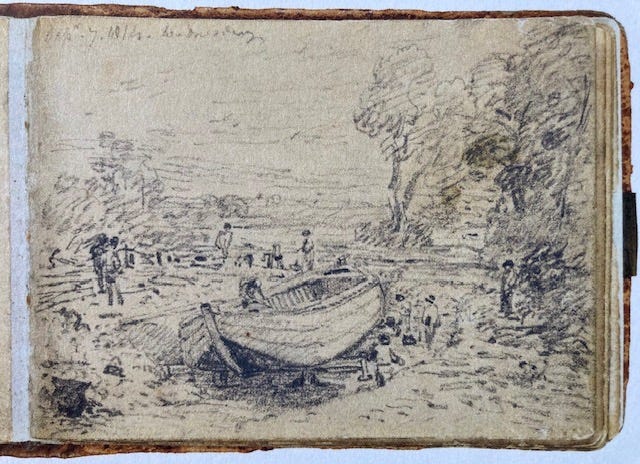

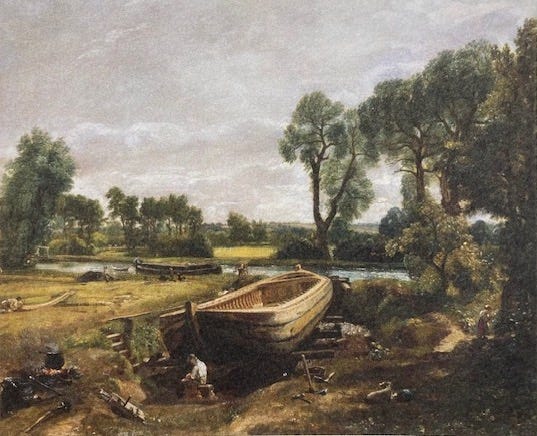

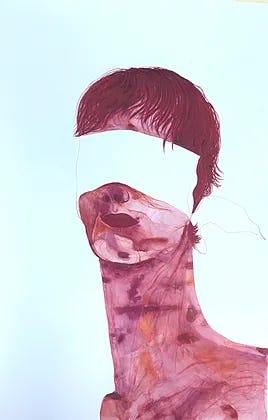

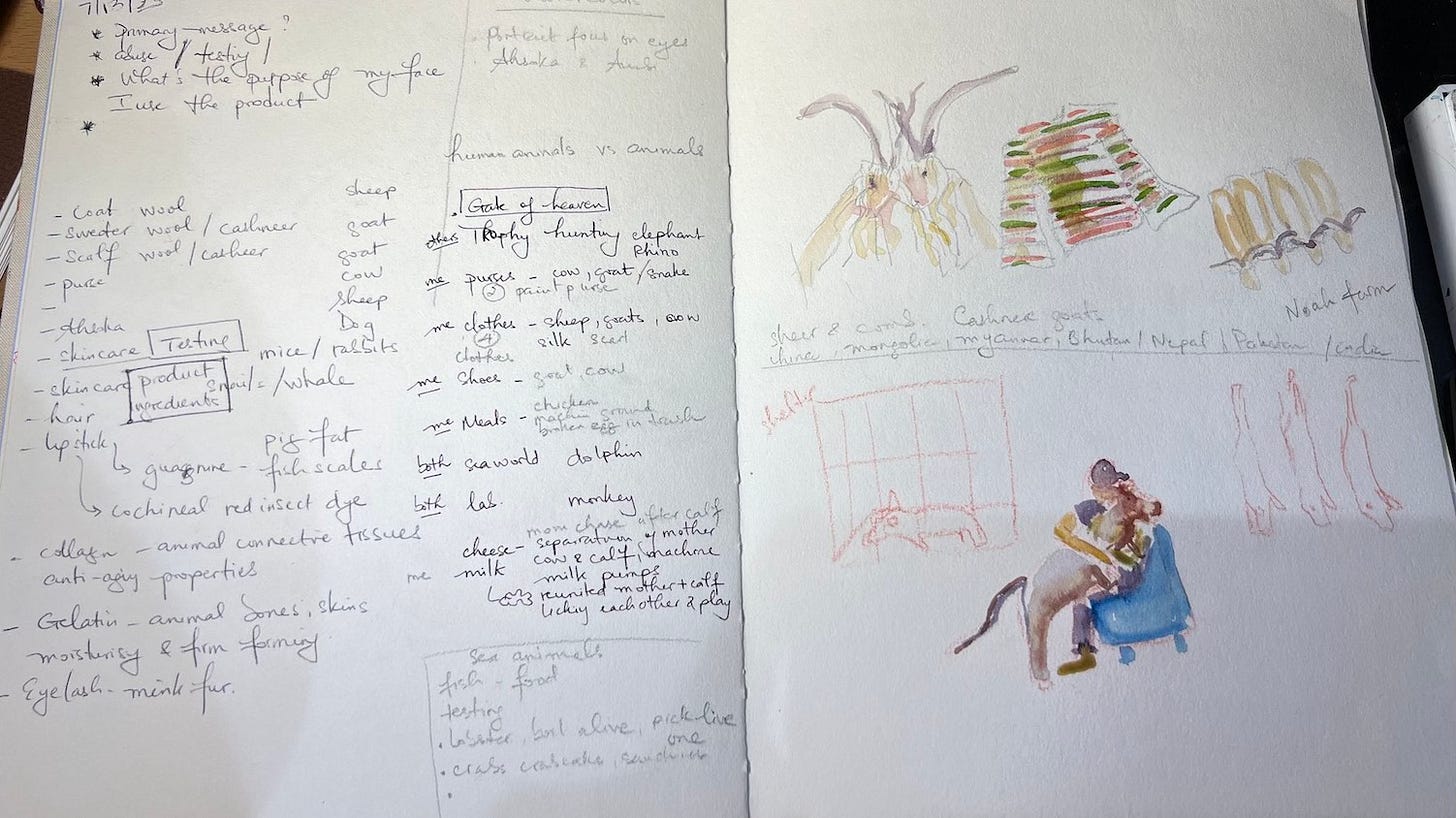

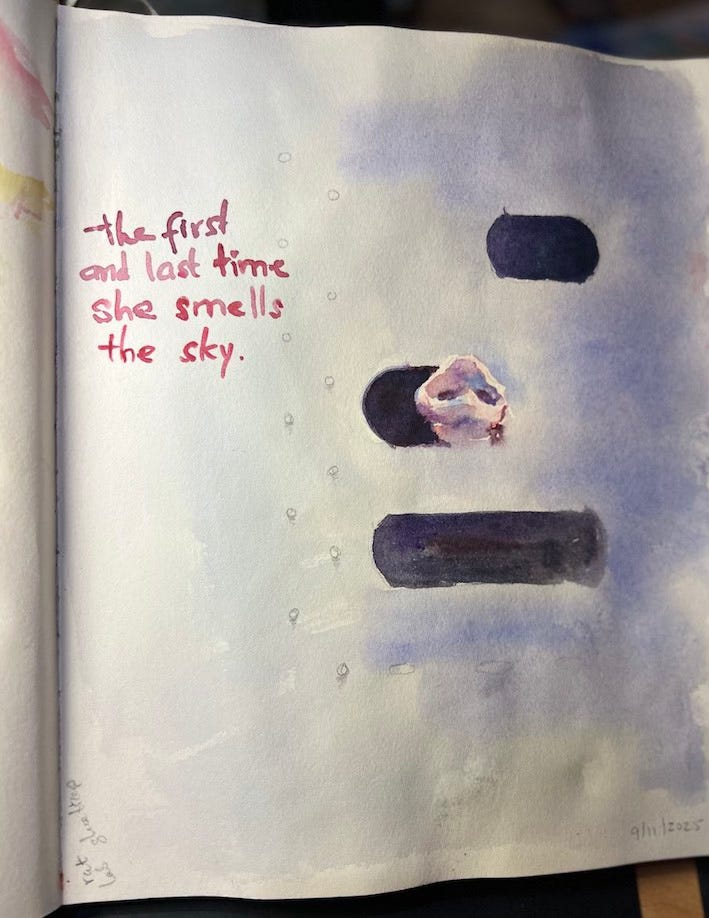

A couple of weeks ago in this newsletter I included a sketch made by David Bowie, which prompted one of my readers, Ann Pham, to share some of her sketches with me. Ann always carries a travel watercolour set and a sketchbook with her, and uses any gaps in time to draw and write — when she’s travelling, in a cafe, between meetings. Her current body of work is about animal welfare, and she makes written notes on the research she does alongside her sketches.

Ann’s pages here epitomise the idea that the sketchbook is where you see the artist thinking it all out. It’s not the polished canvas or the finished sculpture, but the place where ideas tumble onto the page as visual notes, half-formed thoughts, and experiments in line and colour. It’s an intimate visual diary, a way of working through the world with a pencil or brush in hand — observing or imagining a figure, a landscape, an animal, copying a favourite artwork.

Sketchbooks are visual journeys and memory banks: they store details, impressions, and fleeting ideas, often laced with scribbled text or pasted-in images or photos. Sometimes they drift into something else — when does a sketchbook become an album? That in-between quality is part of their fascination.

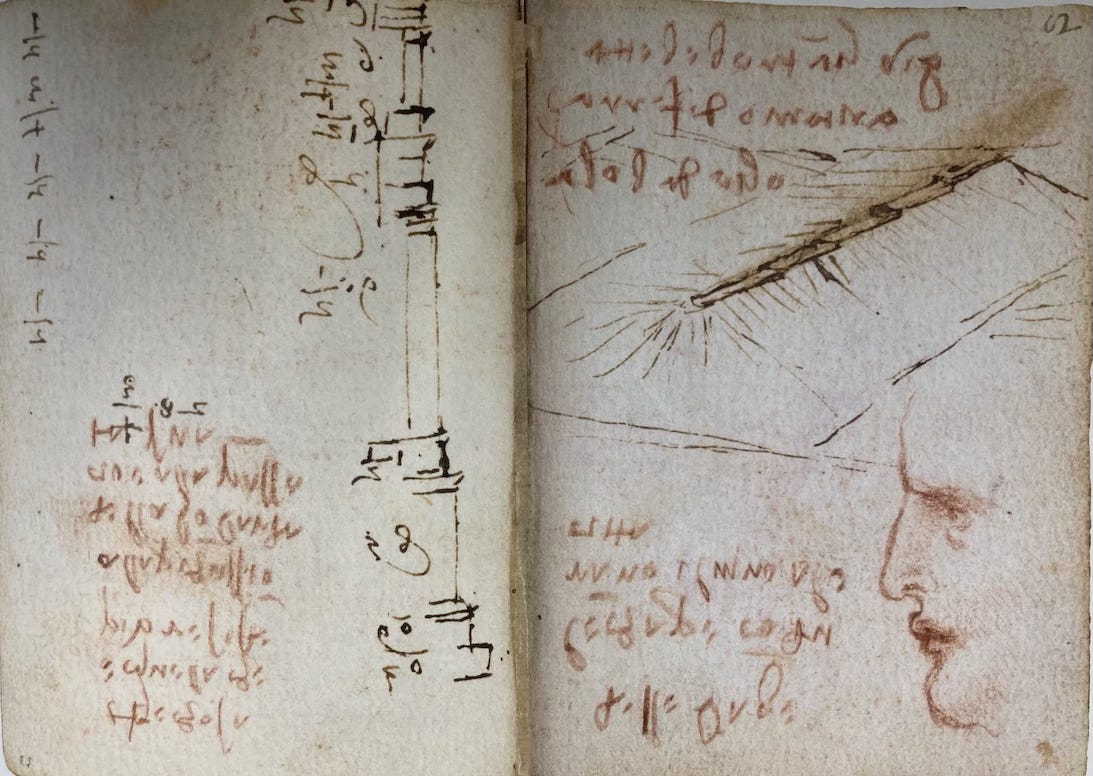

We know that sketchbooks in their bound form have been around since the 15th century as demonstrated by Leonardo Da Vinci, but they became widespread in the 18th century, when mass-produced paper, pencils, and portable watercolour boxes made them affordable companions. Suddenly, everyone from the amateur traveller to the professional painter could carry one.

Today the tradition has expanded: digital sketching apps have turned tablets into portable studios, with artists like David Hockney enthusiastically embracing the iPad as a 21st-century sketchbook.

Artists, do you carry a sketchbook with you all the time or is it a studio thing? Are your sketchbooks private, or are you happy to show them to others? When you’re sketching are you mostly observing the world or developing new ideas? Do you write notes alongside your sketches? Have you tried digital sketching — and if so has it changed things for you? What do you think your sketchbooks reveal about your process that a finished piece can’t? I’d love to know your thoughts.

Pretty unethical art?

I’ve been following an intriguing recent news story about the New York-based Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang involving gunpowder, corporate branding, environmental damage, the Chinese Communist Party, and the power of Chinese social media. For me the story raises a few ethical questions about making art today.

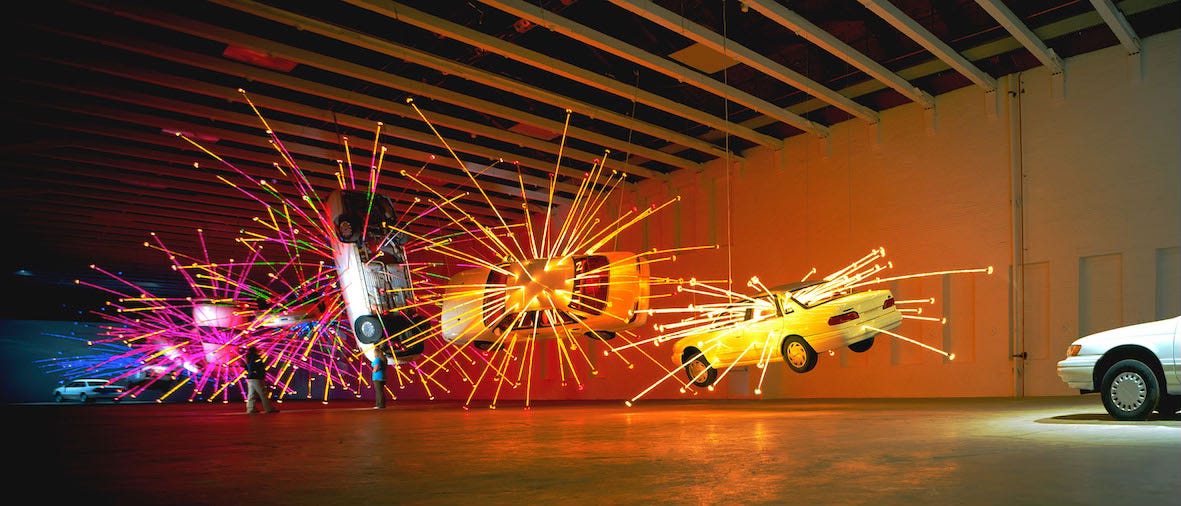

For those of you unfamiliar with Cai’s work, here’s a brief summary: he was born in 1957 in China, and left for Japan in 1986 where he developed his signature gunpowder drawings; in 1995 he moved to New York where he has produced some of his most famous works including Transient Rainbow (2002), a firework piece that created the illusion of a rainbow over Roosevelt Island; Inopportune: Stage One (2004), in which he froze cars in mid air as though they were mid-explosion; and Sky Ladder (2015), a 500-metre-long firework piece resembling a ladder rising into the sky; in 1999 Cai won the Golden Lion award at the Venice Biennale; he also directed the fireworks for the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

For more background on Cai, this is a great video about his career, major works and his thoughts on his practice:

But back to the story. A few days ago Cai staged the work Rising Dragon in the foothills of the Himalayas in Tibet, in collaboration with the clothing brand Arc’teryx. The artwork, which represented a dragon snaking up the mountainside, immediately ignited controversy and condemnation on Chinese social media about the environmental harm it might have caused. The local branch of the Chinese Communist Party launched an official investigation and both Arc’teryx and Cai issued public apologies.

The incident highlights tensions between the use of art in corporate branding and ecological accountability, as critics argued that such a display was reckless in a fragile ecosystem. The Chinese middle classes on social media are popular consumers of the Arc’teryx brand, and it reveals a heightened sensitivity within China to environmental stewardship and corporate responsibility. Interesting.

Also interesting was the response of the Chinese Communist Party, which rushed to promise an investigation. I wonder whether this was partly an attempt to shore up Cai’s reputation, which the Party champions both in China and abroad. Cai’s work is an example of the ‘soft power’ of art: in China he is celebrated as a cultural ambassador whose grand spectacles project national pride.

I was also interested in the location for this artwork: why did Cai choose to stage the work on the Tibetan Plateau, a politically contested area ruled over by China? In my mind I can’t help comparing Cai with Ai WeiWei, the outspoken, dissident Chinese artist whose criticism of the tyranny, corruption and cruelty of the communist regime has been a clear theme throughout his career. Cai, on the other hand, has never talked about his personal views on the Chinese government, and the themes in his work are more universal than directly political. Some critics have therefore raised questions about the meaning of his work, given Cai’s known collaborations with the Communist Party in state projects like the Beijing Olympics: is he complicit with or subtly critiquing the political system in China? Or is it all just simply a pretty spectacle?

Cai’s Rising Dragon piece — and his work in general — raises some questions for me about the ethics of making art and I wondered whether you had any thoughts in response:

His pyrotechnic work is very loud and dirty, and clearly disrupts any local natural environment in which he creates it, so should he not produce this work at all? Given that it’s impossible for most artists to be completely sustainable in their practice, where do you draw the line? This is a subject I’ve written about before, and I’m still not sure what I think.

His firework pieces are expensive to produce and without corporate sponsorship he wouldn’t be able to make them. But does creating art for branding purposes compromise its cultural value — or is it just a realistic means to an end in today’s cultural climate? Would you turn down cash from a corporate sponsor to help you make your art?

And finally, do we expect too much when we want artists from authoritarian states to openly oppose their governments, or is that demand central to how we value their work in the West?

Three exhibitions I’d like to see

Ghosts: Visualising the Supernatural, Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland until 8 March 2026. Do you believe in ghosts? This major exhibition brings together more than 160 works spanning 250 years. From 19th-century spiritualism and theatrical trickery to contemporary art, it explores how ghosts linger in our collective imagination, blurring the line between science, superstition, and the unseen.

Giorgio Armani: Milano, per amore, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, until 11 January 2026. This one’s for the fashionistas amongst you: a poignant final project from the late designer that places over 120 of his garments in dialogue with Renaissance masterpieces by Caravaggio, Bellini and Raphael. More than a fashion show, it’s a meditation on colour, atmosphere and light, revealing unexpected echoes between Armani’s tailoring and the drama of historical artworks.

Cai Guo-Qiang: Gunpowder and Abstraction 2015–2025, White Cube, London, until 9 Nov 2025. Why not go and see some of Cai’s work and let me know what you think? This particular show focuses on the reintroduction of colour into his gunpowder pieces since 2015.

News from Gallery Companion readers

Romanian artist Laura Partin has been accepted to an artist residency in Lloret de Mar in Spain in October. She will be developing a series called Mar Adentro about the decline of marine biodiversity in the Anthropocene and mythological figures from different cultures related to the sea.

Kirsty Harris is showing in a group exhibition & Still Different Worlds at Thames-side Studios Gallery in London from 18 Oct to 2 Nov. Harris’s practice centres around the violent, man-made events that scar the landscape: the detonation of the atomic bomb — and the awe, the absurdity and the abhorrent nature of human ambition.

That’s all for today, GC readers.

Please help me spread the word about this newsletter by clicking like or restack. Or better still, share it with someone you think will enjoy what I write. Thanks for reading!

I have made a number of studio notebooks which are a mix of lists, comments on my own and other people’s work, and drawings. These are usually a quick record of a new idea; a way of capturing the freshness of first configurations.

My initial thought about environmental issues was that it’s based on personal awareness no matter how much news is readily available. And someone who is famous as Cai, the work was destined to get called out though I am surprised not sooner with the impacts of large firework projects to the environments. Interesting indeed. Regarding your third question, I’m certain there are a lot of conversations going when artists are in such state but I think it’s a personal call for an artist to openly oppose their government depending on the level of risks to their own life, family and community they’re willing to take, and the support the get. The shift in an artist’s work can be in a wide range from subtle to in-your-face messages.

Thank you for stimulating my brain again and the feature of the sketches.